Book Review | ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’: The British Far Right since 1967 edited by Nigel Copsey and Matthew Worley

‘Tomorrow Belong to Us’: The British Far Right since 1967, edited by Nigel Copsey and Matthew Worley, offers an interdisciplinary collection that explores the development of the British far right since the formation of the National Front in 1967, covering topics including Holocaust denial, gender, activist mobilisation and ideology. Katherine Williams recommends this insightful and dynamic volume, which shows the importance of new approaches and methodologies when it comes to examining the rise of the far right in Britain.

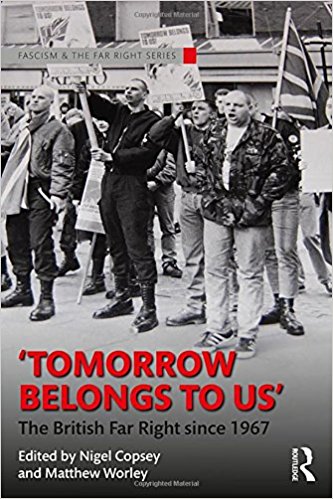

Image Credit: National Front March, Yorkshire, UK, 1970s (White Flight CC BY SA 3.0)

‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’: The British Far Right since 1967. Nigel Copsey and Matthew Worley (eds). Routledge. 2017.

Part of Routledge’s Fascism and Far Right series, ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’: The British Far Right since 1967, edited by Nigel Copsey and Matthew Worley, has its finger firmly on the pulse of contemporary debates surrounding the development of the far right in Britain, which have gained particular currency once more following the Brexit referendum of 2016.

As the editors note in the introductory section, the rise of neo-nationalist or nativist populism has become increasingly difficult to ignore, particularly given radical right mobilisation across Europe and the election of political outlier Donald Trump to the US presidency. To make sense of present-day events, they posit that an understanding of the past is essential to contextualise the British far right today. Thus, 1967 is a particularly significant moment with which to begin the discussion: the National Front (NF) was formed in this year, marking the first time since Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) that far-right groups in Britain came together under one united ‘front’.

While the NF today presents no tangible threat in terms of electoral politics – it has no elected representatives at any level of government – it enjoyed considerable success in 1977 when it won a quarter of a million votes in the Greater London council elections. Following this precedent, 33 years later, the British National Party (BNP) stood 338 candidates and amassed half a million votes in the 2010 General Election. However, despite the relative successes of the NF and BNP at the ballot box, the volume is concerned with the establishment of a ‘new way’ of viewing the far right. The editors aim to move beyond the methodological approaches of ‘hard politics’, eschewing the statistical analysis typifying the field more generally. Thus, the topics discussed in this volume are approached from diverse, interdisciplinary epistemological and methodological perspectives, including scholars in history, cultural studies and behavioural studies, to name but a few.

The ultimate aim of the volume is to bridge gaps in the existing literature, and take analyses of the far right in directions that have yet to be explored or are currently underexplored. The volume is comprised of twelve principal chapters, including an extensive bibliographic survey of primary and secondary source materials pertaining to the British far right. The chapters themselves discuss a variety of topics ranging from homophobia in the BNP, the impact of Greece’s Golden Dawn on British far right parties as well as far right and punk youth culture during the 1970s, illustrating the interdisciplinary nature of the collection.

In the first chapter, Mark Hobbs asserts that, alongside 1967, 1945 is also of utmost significance when it comes to examining the link between Holocaust denial and the subsequent development of far-right ideology. While Holocaust denial presents something of a barrier to the political legitimacy groups like the NF were seeking, it contributed to the construction of what Hobbs terms a ‘false history’. According to this view, the failure of far-right movements to attain legitimacy is blamed on Jewish conspiracies, of which the Holocaust itself is considered one such example, and further ‘evidence’ of Jewish ‘interference’ in global politics. The many crimes of the Nazi regime are, of course, conveniently ignored.

Holocaust denial had no ‘official’ place within the NF, but influential members, such as John Tyndall, held different views; he was not afraid to ‘retract’ these beliefs publically in order to secure power and influence within the movement before becoming party leader in 1972. The publication of Did Six Million Really Die? by Richard Verrall in 1974 saw the far right attempt a bid for legitimacy that went beyond the ballot box. Hobbs notes that this infamous tract was meant to imbibe far-right propaganda with scholarly credentials: the authorship was attributed to an academic institution, and the text was presented with footnotes, references and a bibliography. This was designed to lend further credence to the idea that Holocaust denial could be a ‘viable’ form of historical revisionism. This tradition was continued by the revisionist Journal of Historical Review, and cast into the public eye by libel cases brought against prominent figures in the movement like Ernst Zündel and David Irving.

It is far too easy to fall into the trap of suggesting that Holocaust deniers and proponents of far-right ideology are ‘mad’ or stupid. As Hobbs asserts, ignoring these views is to overlook the serious danger posed by both the ideology itself and the violence it facilitates. Similarly, we cannot underestimate the danger posed by ‘alt right’ groups today, despite their academic veneer – Richard Spencer’s National Policy Institute being a case in point – and seemingly inconspicuous stylings (for readers interested in this particular subject, Chapter Seven, by Ana Raposo and Roger Smith, offers a wealth of discussion on far-right visual cultures as they pertain to British movements). Hobbs effectively demonstrates that Holocaust denial is an essential part of the inner workings of far-right ideologies that not only sustain epistemological ‘grand narratives’ of a Jewish conspiracy, but continue to ‘unify’ like-minded individuals, as events in Charlottesville last year have shown.

This ‘unification’ is also facilitated through the proliferation of far-right ideology on social media sites, despite recent ‘purges’ by platforms such as Twitter. Consequently, far-right groups are able to reach out to potential members, as well as altogether different types of audiences, from the comfort of their own homes. In Chapter Nine, Hannah Bows discusses the relative lack of research undertaken on one particular potential audience: women. Despite the rise in academic interest in the far right, the author notes that studies have been dominated by ‘salient’ images of angry, white, working-class men, often absenting women from the discussion altogether. As Bows reiterates, we therefore know ‘painfully little’ about women in the British far right, historical studies notwithstanding. Subsequently, the chapter aims to provide a theoretical overview of the relatively small pool of research that exists.

Bows discusses research, both qualitative and quantitative, that attempts to unpack why a ‘gender gap’ in discussions of women’s participation may exist. Four key strands of thought emerge: men dominate manual occupations and are more likely to be affected by a lack of employment opportunities; women may be more religious than men and find the far right antithetical to their personal beliefs; the diffusion of feminism has seen women turn their backs on the far right; and, finally, society’s rigid adherence to gendered binaries has seen both men and women socialised into ‘knowing their place’. Whilst this may offer researchers insight into some of the reasons behind women’s alleged non-involvement, Bows argues such studies are limited not only by small sample sizes and altogether different methodological approaches, but also the difficulty in predicting levels of female participation due to the secretive and non-formal membership processes of far-right groups.

Although the far right is dominated by men, we know that women are active in the movement both at home and beyond – Britain First’s deputy leader Jayda Fransen and Germany’s Beate Zschäpe are high-profile examples. Influential studies undertaken by sociologist Kathleen Bleehave also attempted to shed some light on women’s involvement in neo-Nazi and Ku Klux Klan (KKK)-affiliated groups in a US context. Bows posits that as well as an innate ‘paucity’ of empirical research, there is an almost total lack of theoretical engagement: dominant theories inevitably centre men’s experiences and cannot simply be transferred to women. The author opines that while feminist scholars in particular may have trouble reconciling far-right agendas with feminism’s core tenets of agency and equality, the rise of far-right movements and their gender-specific appeal are hugely important to feminist theories and activism. Ultimately, what we need, and what Bows advocates, is empirical research that engages directly with women in far-right groups in order to effectively unpack dominant socio-cultural narratives surrounding their involvement.

‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’ offers readers a dynamic insight into the development of the British far right since 1967, and reminds us that despite its various peaks and troughs, the movement continues to have the ability to incite hatred and undermine democracy, as recent events have also shown. Contributors to this excellent volume advocate a new way of looking at the far right in Britain, and demonstrate a range of means through which intersectional engagement can be achieved, all the while encouraging researchers to look beyond the statistical methods of the ‘hard’ sciences for ‘answers’ regarding the subject matter at hand. The book is a must-read for researchers and general readers alike.

This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on the LSE Review of Books blog.

Katherine Williams is an ESRC-funded PhD candidate at Cardiff University. Her research interests include the role of women in far-right groups, feminist methodologies and political theory and gender in IR. You can follow her on Twitter: @phdkat. Read more by Katherine Williams.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.