The limitations of opinion polls – and why this matters for political decision making

Recent research by Jennings and Wlezien has demonstrated that political polling has remained as accurate as ever in terms of margin of error in the week prior to an election. However, polls are usually publicly judged on whether they call the result correctly. In this, writes Sean Swan, they have been less accurate over recent UK elections. This has particular consequences for how and when political leaders make decisions about discretionary elections, and so it matters that we understand polls and their limitations correctly.

Image: Absolutelypuremilk, via a (CC BY-SA 4.0) licence

Image: Absolutelypuremilk, via a (CC BY-SA 4.0) licence

In the immediate wake of last year’s surprise general election result, the Guardian’s Peter Preston, in an article uncompromisingly entitled ‘Inaccurate opinion polls are what got us into this mess in the first place’, noted that opinion polls ‘underpin decisions as well as headlines’ then asked:

Would David Cameron have promised a European referendum if he hadn’t thought another Lib Dem coalition, ruling it out, was on the cards? Would Theresa May – wallowing in 23% polling leads in April – have walked the 8 June plank?

In a similar vein to Preston, the Sturgis inquiry into the 2015 polling miss stated that the ‘poll-induced expectation’ of a Labour/Conservative tie ‘undoubtedly informed party strategies and media coverage’ and ‘may ultimately have influenced the result itself’.

A recent research article by Will Jennings and Christopher Wlezien, ‘Election polling errors across time and space’, received considerable media attention under headlines such as ‘Polls as accurate as they have ever been, study says’ and ‘No evidence of crisis in election polling, study finds’. The Guardian article reassures its readers that ‘poll accuracy was found to have remained stable over time, and might even have improved.’ Jennings and Wlezien’s report is based on a meta-analysis of over ‘30,000 national polls from 351 general elections in 45 countries between 1942 and 2017’. It found that a contemporary (2015–17) polling error of 2.6 percentage points is just 0.2 points higher than in the period from 1942 to 2013.

However, such general reassurances based on a meta-analysis of polls from different decades and different countries, are insufficiently satisfying in the particular context of the UK in the last decade. As Lord Lipsey, Chairman of the House of Lords Select Committee on Political Polling and Digital Media, put it: ‘[i]n the last seven general elections pollsters have got the result wrong three times’.

Furthermore, opinion polls are judged not on their statistical accuracy. As the Sturgis inquiry observed: ‘public assessments of polling performance seldom rely on statistical measures of error such as the MAE [mean absolute error], but instead whether the election result is called correctly, in terms of the likely composition of the ensuing government.’ As Lord Lipsey, pointed out in the Guardian:

We often read that there is a plus or minus 2 or 3% statistical margin of error in a poll. But what we are rarely reminded of is that this error applies to each party’s vote. So if a poll shows the Tories on 40% and Labour on 34%, this could mean that the real situation is Tory 43%, Labour 31% – a 12 point lead. Or it could mean both Tory and Labour are on 37%, neck and neck.

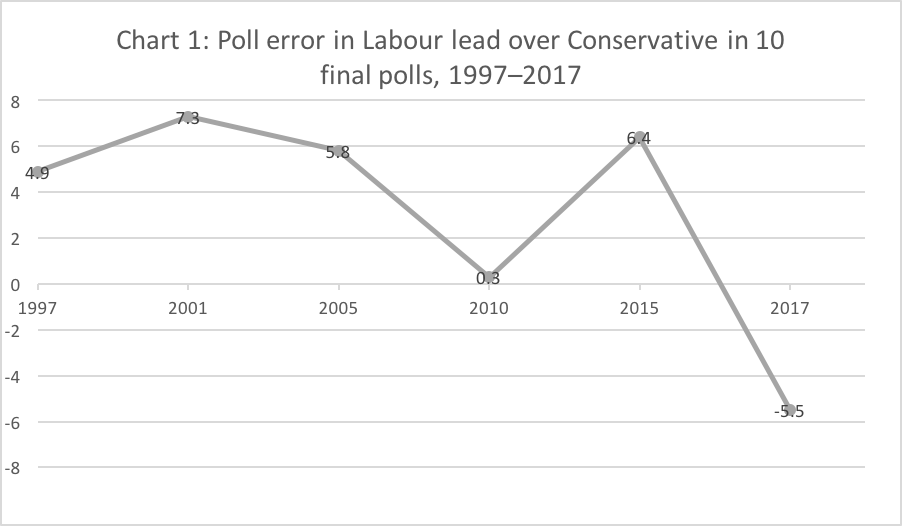

And it is here, in the lead of one party over another, that there has been growing inaccuracy in UK polling with ‘increasing under-estimation of the Conservative/Labour lead’ (Sturgis, 20). The exception to this rule was in 2017 when there was a gross over-estimation of the Conservative lead (6.1% in polls conducted by British Polling Council affiliated pollsters in the final week versus the election result of 2.5%; see Chart 1), possibly an over-correction by the pollsters of a previous tendency to under-estimate the Tory lead.

Source: final 10 published polls by PBC members for each election (final 13 in 2015 owing to a number of polls being completed on the same day).

Typical polls for the 2017 UK general election had a sample size in the 1,200 to 2,200 range. The margin of error of a poll with a sample size of 1,200 is roughly 3 percent, while a sample of 2,200 will have a margin of error of 2 percent. Thus, for a poll with a sample size of 1,200 which shows Labour on 35 percent and the Tories on 34 percent, this poll would be statistically ‘accurate’ in relation to each of the following hypothetical results in that each is within the margin of error of the poll:

| RESULT A | RESULT B | RESULT C |

| Labour 38% | Labour 32% | Labour 33% |

| Conservatives 31% | Conservatives 37% | Conservatives 33% |

Statistical accuracy is not what is sought by political pundits and other consumers of opinion polls, such as the media and politicians. They want to know who is likely to win the election. But it gets worse. The 3 percent margin of error is the most accurate such a poll can be. If there are errors in the polling methodology, such as unrepresentative samples (which the Sturgis inquiry found to be one of the reasons for the 2015 polling miss), the margin of error will be correspondingly greater.

The focus of Jennings and Wlezien’s research was on the accuracy of polls in the final week of campaigns. However, given the prevalence of discretionary votes in the UK, it is not only the accuracy of the polls in the final week that is relevant, but the accuracy of the polls at the point in time at which the decision to hold a referendum or call an early general election is made. Even without knowing what exact impact the polls had on David Cameron’s decision to hold the Brexit referendum or on Theresa May’s decision to call an early general election in 2017, it is possible to pose the question ‘How helpful would the polls have been in making these decisions?’.

On 20 February, 2016, David Cameron announced that he would hold a referendum on British EU membership on 23 June. In the eighteen polls conducted in 2016 prior to Cameron’s referendum announcement, Remain had an average 3.4 percentage point lead. The referendum was still 122 days off, but Jenkins and Wlezien found that historically polls 200 days out have a margin of error of approximately 3.3 percentage points for legislative elections and 5.4 points for presidential elections. Given their binary nature, referendums more closely resemble presidential elections than elections to legislatures. The referendum resulted in a 3.8 percentage point lead for Leave. The polls available at the time Cameron made his decision were thus broadly within the margin of error but were still pointing in exactly the wrong direction, as far as Cameron was concerned.

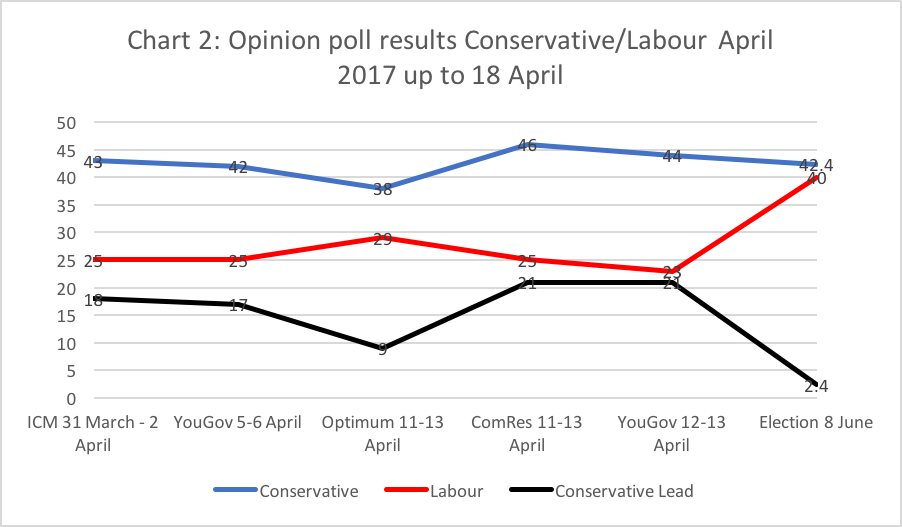

When Theresa May decided to opt for an early general election on 17 April 2017, the average poll lead for the Conservatives over Labour was 17 points for the month of April up to then (see Chart 2). True, the election was still 50 days off, but Jennings and Wlezien had found that polls taken 50 days in in advance of an election had a margin of error of ‘approximately 3 points’ (9). The eventual Conservative lead would be only 2.4 percentage points – a result 14 points in excess of Jennings and Wlezien’s 3-point margin of error for polls conducted 50 days prior to election day.

Sources: YouGov/The Times 12–13 April 2017; ComRes/Sunday Mirror, Independent on Sunday: 11 & 13 April 2017; Opinium/Observer: 11–13 April; YouGov/The Times: 5–6 April; ICM/Guardian Poll 31 March–2 April

Thus, while Jennings and Wlezien’s research may provide some statistical comfort to the polling industry internationally, this provides little reassurance in the particular case of recent serious British polling misses. In addition, even where polls are ‘statistically’ accurate – that is, are within the polls’ margin of error – they can be inaccurate in terms of predicting election results. Opinion polls may be ‘all we have’ but they can be positively dangerous politically if their limitations are not properly understood.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Sean Swan is a Lecturer in Political Science at Gonzaga University, Washington State, in the USA. He is the author of Official Irish Republicanism, 1962 to 1972.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.