England’s local elections 2018: the Lib Dems’ performance was underwhelming – but these were not the elections to judge the party on

Despite media headlines to the contrary, the Liberal Democrats’ performance in the recent local elections was pretty underwhelming, explains David Cutts. But it is the 2019 local elections that will tell us more about the long-term viability of the party, since those will concern a larger number of English districts where the Lib Dems will be seeking to reclaim ground lost to the Conservatives since 2010.

Vince Cable. Picture: Richter Frank-Jurgen, via a (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence

Liberals have a longstanding attachment to the local. Aside from their enduring commitment to community politics, the Liberal Democrats have always relied on winning council seats and running local councils to counter voters’ electoral credibility concerns. The formula has always been a simple one: grassroots politics provided the basis for winning seats and building local core support. Elected councillors would ‘fly the flag’ for the party through their ‘all year round’ activism. With the help of national party strategists, they would become experienced, skilled local campaigners adept at targeting and recruiting activists, and building local party organisations.

Local success boosted the party’s chances in Westminster elections as voters were more likely to support the Liberal Democrats where it had a chance of winning, thereby diluting concerns that voting for the party would be a wasted effort. Although not full-proof, it had a proven record of success. While the strength of the Liberal Democrats’ local base largely endured in opposition, it collapsed during its years in coalition government. Reduced to eight seats at Westminster in 2015 and showing only ‘green shoots’ of a recovery two years later, rebuilding the party’s local infrastructure has become a top priority for the newly elected leader Vince Cable. With the party struggling to get ‘political air time’ and questions about its long-term future seemingly unresolved, the Liberal Democrats were in dire need of an electoral boost and positive headlines.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2018 local elections, that is exactly what it got. After a net gain of 75 council seats and winning control of four additional councils, Cable faced the media to proclaim that the “beginning of the fight back” had begun. But do these results suggest that the ‘cockroaches’ of British politics are about to mount a comeback or is such talk premature? The national picture leans more to the latter.

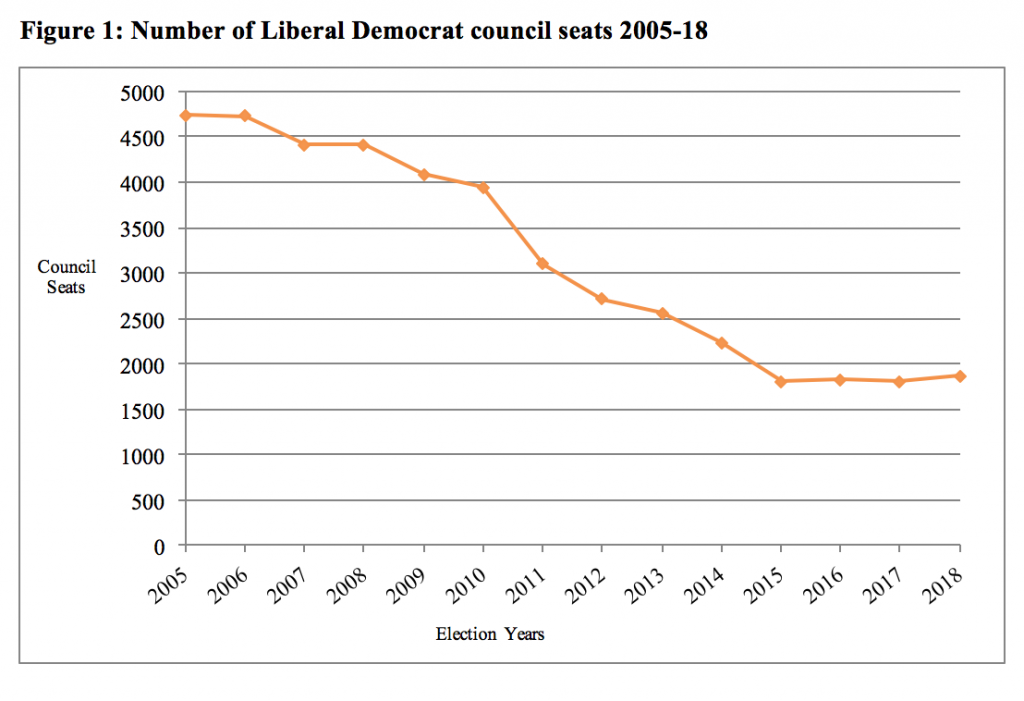

At 16%, the Liberal Democrats projected national share of the vote was much higher than current nationwide poll ratings and 3 percentage points higher than in 2014. On the downside, it was 2 percentage points lower than in the 2017 local elections. Moreover, in terms of nationwide share of the vote, it was one of the worst local election performances since the party’s formation. The Liberal Democrats currently have just shy of 1900 councillors. To put this into some context, they would have to more than double that number just to return back to their 2010 local council composition (see Figure 1).

Nonetheless there are some discernible trends. The Liberal Democrats did better in areas where they have longstanding prior support or local representation. The party targeted taking control of Kingston upon Thames and neighbouring Richmond in South West London where they have enjoyed recent success both locally and at Westminster. While local pacts with the Greens in Richmond aided their cause, the scale of the Liberal Democrats’ success surpassed expectations and offset local problems in neighbouring Sutton where the party lost seats to the Conservatives but retained overall dominance. Elsewhere there were positive performances in pre-coalition local strongholds – Cambridge, Cheltenham, Portsmouth, St Albans, Watford, and Winchester. Success was not entirely confined to the south of England. Gains in Hull and Sheffield councils, both of which the Liberal Democrats controlled in the late 2000s, also suggested that the party did better where it was previously strong.

Nonetheless there are some discernible trends. The Liberal Democrats did better in areas where they have longstanding prior support or local representation. The party targeted taking control of Kingston upon Thames and neighbouring Richmond in South West London where they have enjoyed recent success both locally and at Westminster. While local pacts with the Greens in Richmond aided their cause, the scale of the Liberal Democrats’ success surpassed expectations and offset local problems in neighbouring Sutton where the party lost seats to the Conservatives but retained overall dominance. Elsewhere there were positive performances in pre-coalition local strongholds – Cambridge, Cheltenham, Portsmouth, St Albans, Watford, and Winchester. Success was not entirely confined to the south of England. Gains in Hull and Sheffield councils, both of which the Liberal Democrats controlled in the late 2000s, also suggested that the party did better where it was previously strong.

Broadly speaking, the Liberal Democrats’ performance is in line with past trends. The party always tend to perform better against the incumbent government than the opposition. The Liberal Democrats did far better in shire councils predominantly against the Conservatives than in Metropolitan areas where they were largely fighting Labour. One notable example is South Cambridgeshire, where the Liberal Democrats took control for the first time. Elsewhere, the party gained ground in parts of Surrey and Hertfordshire largely at the expense of the Conservatives.

By contrast, notwithstanding its success in Sunderland – the best liberal performance since 1984 – and a small resurgence in Liverpool, the Liberal Democrats seem to be going backwards in Metropolitan areas. Across the 34 Metropolitan boroughs up for election, the Liberal Democrats secured 16 fewer seats than at the height of the party’s local collapse four years previously. It currently holds only a third of the seats it did in 2010. The picture is also less rosy than what it seems across the capital. Although the Liberal Democrats won 35 more seats across London than in 2014, nearly three-quarters of their councillors are in its strongholds of Kingston, Richmond, and Sutton. Of the 32 London boroughs, only nine contain Liberal Democrat representatives compared to 14 four years ago.

The Liberal Democrats also performed better in places with larger numbers of graduates and those working in education. This suggests a reconnection with traditional liberal supporters and more than likely the successful mobilisation of ‘latent liberals’ turned off during the coalition, but now keen to return to the fold. Despite some circumstantial evidence of the party squeezing Labour support in ward battles with the Conservatives, any re-establishment of pre-2010 tactical alliances still looks a long way off as the party continues to battle with the legacy of coalition.

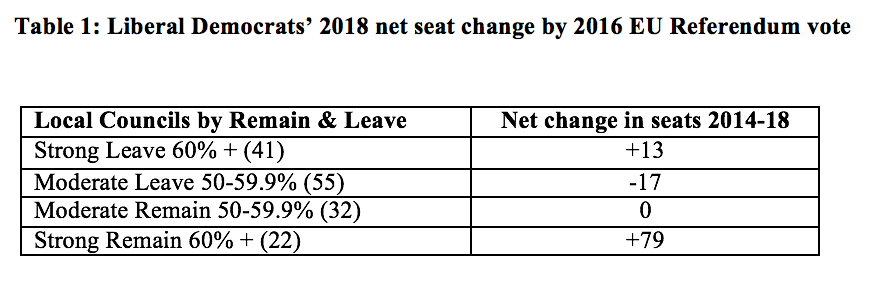

The Liberal Democrats seemingly face an uphill task fighting the increasingly polarised demographics of Labour and Conservative support. The spectre of Brexit also continues to cast a large shadow on electoral proceedings. And as with other elections since the EU referendum, there is little evidence that the party of ‘Remain’ are persuading ‘Remain’ voters to join the fold. Figure 2 shows no discernible pattern with the line of best fit unduly influenced by strong performances in Richmond and Kingston.

In ‘Strong Leave’ areas, the Liberal Democrats actually made a net gain of 13 seats whereas they lost ground in those local authorities with a ‘Moderate Leave’ vote. By contrast, the party made a net gain of 79 seats in ‘Strong Remain’ areas although 65 gains were in three councils. In 12 of the 22 councils where the ‘Remain’ vote was above 60%, the party failed to make any gains and in two councils it lost seats. The Liberal Democrats also failed to gain any ground in ‘Moderate Remain’ areas.

Despite the favourable media headlines, the Liberal Democrats’ nationwide performance was pretty underwhelming and did little to suggest that a return to the top table of British politics is imminent. These, however, were not the elections to judge the party on. Next year’s local elections are across a larger number of English shire districts including parts of the south west where the Liberal Democrats will be seeking to reclaim ground lost to the Conservatives since 2010. This will provide a far better indication of where the party stands. Given the party’s current low electoral base in these councils, the Liberal Democrats will be looking for at least 200 net gains. Anything above this and talk of a comeback would have some validity, but gains around the mark achieved in this election will represent a failure and would inevitably lead to questions not only about Cable’s leadership but the long-term viability of the party.

Despite the favourable media headlines, the Liberal Democrats’ nationwide performance was pretty underwhelming and did little to suggest that a return to the top table of British politics is imminent. These, however, were not the elections to judge the party on. Next year’s local elections are across a larger number of English shire districts including parts of the south west where the Liberal Democrats will be seeking to reclaim ground lost to the Conservatives since 2010. This will provide a far better indication of where the party stands. Given the party’s current low electoral base in these councils, the Liberal Democrats will be looking for at least 200 net gains. Anything above this and talk of a comeback would have some validity, but gains around the mark achieved in this election will represent a failure and would inevitably lead to questions not only about Cable’s leadership but the long-term viability of the party.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog.

About the author

David Cutts is Professor in Political Science at the University of Birmingham. For a full profile see here.

David Cutts is Professor in Political Science at the University of Birmingham. For a full profile see here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.