The many roles of manifestos at the subnational level in British general elections

Alistair Clark and Lynn Bennie assess the roles of national party manifestos across Britain, Scotland and Wales in UK-wide general elections, and illustrate the multiple functions these documents perform in complex multilevel systems of government.

The devolution of powers to new institutions in Scotland and Wales from 1999 has had consequences for the programmes and manifestos that parties campaign on during UK-wide general elections. Many of the policy areas debated in such elections – health, education, policing etc. – no longer apply at the devolved subnational level in that election. To take account of this, the state-wide political parties – Conservatives; Labour; Liberal Democrats – now produce detailed manifestos in each of the three countries that make up Great Britain.

While there has been some research into manifestos in devolved elections, there has been little on how general election manifestos vary at the sub-national level. Nor has such research examined the differing roles that manifestos may perform. We examine these issues as part of a Party Politics special issue on the ‘How’s and Why’s of Party Manifestos’.

We argue that devolution has institutionalised the need for intra-party variation in general election manifestos at the British, Scottish, and Welsh levels. Importantly, we suggest that there is a potential temporal relationship between state-wide parties’ general election manifestos and those used in subsequent elections to the devolved institutions. Understanding these issues is of broader comparative importance given devolving and regionalising moves in a number of countries.

Manifestos have various roles. They help confer mandates on successful parties; they have symbolic significance; and they can be a statement of intra-party democracy. They contribute to responsible party government; they can be used to help force change on reluctant civil servants; and they can amount to a form of advertisements for parties. Integrating this understanding of manifesto roles with the classic vote, office, and policy seeking approach to party goals, we identify three ideal types of manifesto:

- Contract/mandate manifestos are oriented towards office seeking, containing many specific pledges for the immediate election, with relatively little thought given to future positioning. Contract manifestos are associated with parties most likely to form an administration immediately after an election.

- Advertisement manifestos aim ultimately to promote the party, and are associated with vote-seeking parties. This may be vote-seeking for an immediate election, or it may be an effort to build up credibility and support for a future election.

- Identity/principle manifestos are associated with policy-seeking parties, where it may be enough to articulate ideal policies or ideological values. Identity/principle manifestos are also likely to have a considerable degree of future orientation, looking towards the ideal situation where compromise is unnecessary.

The article analyses general election manifestos from 2001 to 2015. We approach the topic by a qualitative reading of the documents, complemented by some simple quantitative analyses. But manifestos can be analysed through more than just words. Analysis also therefore incorporates the form, structure of the documents, and use of photographs and images.

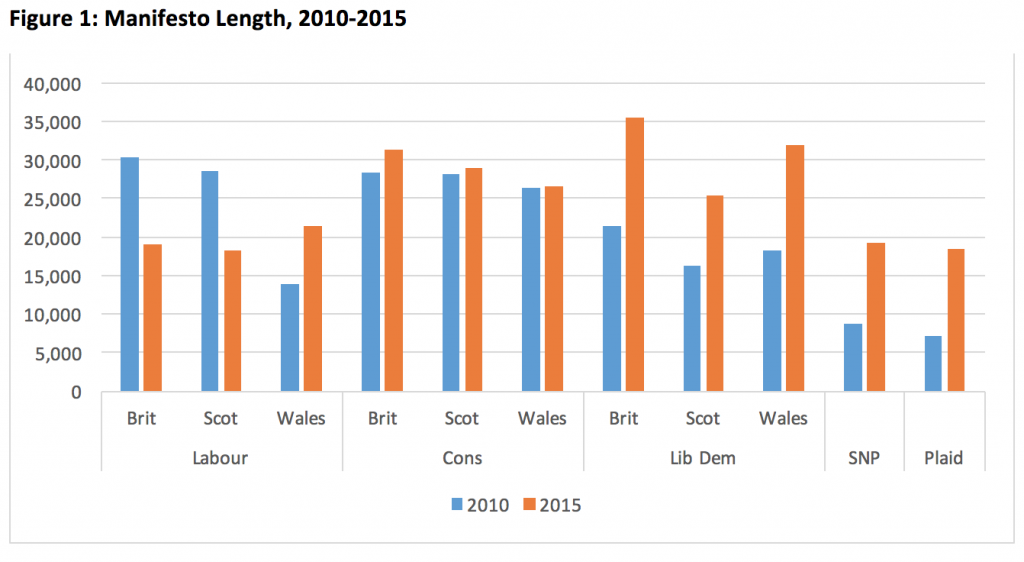

As Figure 1 shows, these are not short documents. The average length across all three main state-wide parties in 2010 was over 23,000 words, while in 2015 it was over 26,000. There is clear variation between parties. In 2010, the Welsh Labour manifesto is less than half the length of its British and Scottish counterparts. In 2015, it is longer than the equivalent Scottish and British documents. Such variation can be seen across all parties.

Differences in structure and use of images are also evident. For example, the 2010 Welsh Labour manifesto is very different from its Scottish and British equivalents. It utilises a different cover, and presents 14, often Welsh-themed photographs. By contrast, the Scottish and British documents look virtually identical and neither offers any images in the main body of the document. Across all parties, there is a rise in the use of photographs between 2010 and 2015, with Plaid Cymru going from as few as seven images in 2010 to 110 in 2015. There are differences in how the parties portray their regional leaders in Scotland and Wales, with the devolved leaders sometimes given star-billing rather than the UK leader.

National identity is increasingly prominent in the Scottish and Welsh manifestos. The Conservative Party is generally most likely to refer to British identity or Britain. For all parties, but with the exception of the Welsh Conservative manifesto in 2010, identity politics in Wales has been emphasised more than in Scotland. We suggest that a focus on a party’s immediate competitors in an election is evidence of mandate/contract manifestos. It is striking that, even in 2010, when the SNP had been in government in Scotland for three years and Plaid Cymru was also in coalition, there is barely a mention of the nationalist parties in their state-wide competitors’ manifestos. It takes Labour until 2015, a year after the 2014 Independence referendum, to make ten references to the SNP, indicating a sluggishness in responding to the nationalist challenge. For both Labour and the Conservatives, across all three manifestos in both 2010 and 2015, the main focus is each other and their competition at Westminster.

A more detailed analysis of Labour manifestos highlights different ways in which policy and devolution has been dealt with. In 2010, the Scottish version appears virtually identical to the British manifesto. Deviation in policy commitments is dealt with by reworking or removing paragraphs, or offering examples of how reserved British-level policies might be implemented in Scotland. There is clear evidence of general election manifestos being used to suggest policies for future devolved elections, in the manner that might be expected from advertisement manifestos. We also find evidence for identity manifestos, Welsh Labour’s 2010 manifesto being a particular example.

Devolution means that parties now must adapt to a complex multi-level environment in UK general elections. As with the vote, policy, and office-seeking model of party goals, the three manifesto types are not mutually exclusive. Evidence of all three may be found in the same manifesto, but in each election one of the three types will be the most dominant, depending on intra-party trade-offs and the context of the election. British general election manifestos contain elements of all of these roles, but advertising and identity-based functions are more prominent at the regional level. An emphasis on decentralization across Western democracies suggests that these insights into party behaviour have broader applicability than just UK politics.

This post represents the views of the authors, and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog, and draws on the authors’ work published in Party Politics.

About the authors

Alistair Clark (@ClarkAlistairJ) is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Newcastle University. His research interests include political parties, elections and political and electoral integrity. The second edition of his book Political Parties in the UK (Palgrave) is due to be published in September 2018.

Alistair Clark (@ClarkAlistairJ) is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Newcastle University. His research interests include political parties, elections and political and electoral integrity. The second edition of his book Political Parties in the UK (Palgrave) is due to be published in September 2018.

Lynn Bennie is Reader in Politics at the University of Aberdeen. Her research interests span the areas of political participation (especially party membership), elections and political parties. Her latest book, with Rob Johns and James Mitchell, The Revival of Party Membership: The Scottish Referendum and Recruitment to Parties, will be published by Routledge in early 2018.

Lynn Bennie is Reader in Politics at the University of Aberdeen. Her research interests span the areas of political participation (especially party membership), elections and political parties. Her latest book, with Rob Johns and James Mitchell, The Revival of Party Membership: The Scottish Referendum and Recruitment to Parties, will be published by Routledge in early 2018.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.