How the partisan context of parliamentary votes affects MPs’ party loyalty on free votes

To measure the extent to which MPs make decisions about how to vote out of agreement with a policy or party loyalty, Christopher D. Raymond measured the variation in MPs’ voting behaviour in a series of free votes. He found that the closeness of each parliamentary division affected MPs’ voting behaviour, indicating that loyalty to their party, and the desire for a partisan win, has an effect independently of an MP’s own position and the party whip.

Picture: UK Parliament, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

Picture: UK Parliament, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

Previous research has noted that MPs are fundamentally motivated to support their party’s policies because they personally support that position (most of the time, at least). On legislation they do not support, party unity may also be enforced by the whip. However, there is growing recognition that MPs may also be moved to support the party position out of a sense of loyalty to their party. Similar to the party identifications of voters, MPs may vote along party lines out of a sense of loyalty rooted in their psychological attachments to their party.

The argument

Much of the evidence for the party loyalty effects has been seen on free votes, where the whips are relaxed and MPs are allowed to vote according to their consciences. Because free votes effectively control for the impact the whips have on party cohesion, and when data measuring individual MPs’ preferences can also be controlled for, the residual cohesion observed on free votes provides evidence that MPs’ loyalty to their parties also influences their voting behaviour. Following this approach, previous research has found evidence of such loyalty effects on issues dealing with human reproduction, the age of consent for same-sex relations, and House of Lords reform. What is less clear in these studies, however, is why the estimated effect of loyalty varies from vote to vote.

In my article in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, I examined the impact that context has on MPs’ voting behaviour. In particular, I examine the impact that the closeness of the vote has on the strength of party loyalty effects on voting behaviour in Parliament. If MPs believe that a vote may be close, the consequences of how they vote increases, which may activate MPs’ party identifications and motivate them to support the party’s position out of a sense of loyalty to the party – net of other factors influencing the vote. In contrast, when bills are expected to pass or fail easily, there is less need to rally behind one’s party, which may result in weaker party loyalty effects.

The analysis

To estimate the impact of context on the degree to which MPs’ party loyalties shape their voting behaviour, I analysed a series of votes on what would become the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008. The HFEA involved a series of free votes to update legislation regulating the treatment of embryos – as well as a few amendments seeking to limit the gestation times at which abortion could be performed. Because the HFEA involved a large number of divisions (20) on the same subject in which the whips were genuinely relaxed, and because data were available to measure MPs’ preferences, this issue offered a unique opportunity to estimate the impact the differences in context of each division had on the residual party loyalties of MPs.

Controlling for several alternative explanations of MPs’ voting behaviour, including survey data measuring MPs’ attitudes towards related issues like abortion, I estimated models predicting votes to oppose the HFEA. Because these were free votes (and so controlling for the effect of the whips), and because the control variables accounted for MPs’ personal (and constituents’) preferences, including dummy variables measuring MPs’ party affiliations, they provided an estimate of the residual party loyalty effect on MPs’ opposition to the HFEA. To determine whether the closeness of the vote explained variation in these party loyalty effects, I interacted party affiliation with the percentage of MPs on each division voting to oppose the HFEA. The higher the percentage (reflecting the closer the vote), the stronger we would expect party loyalty effects to be.

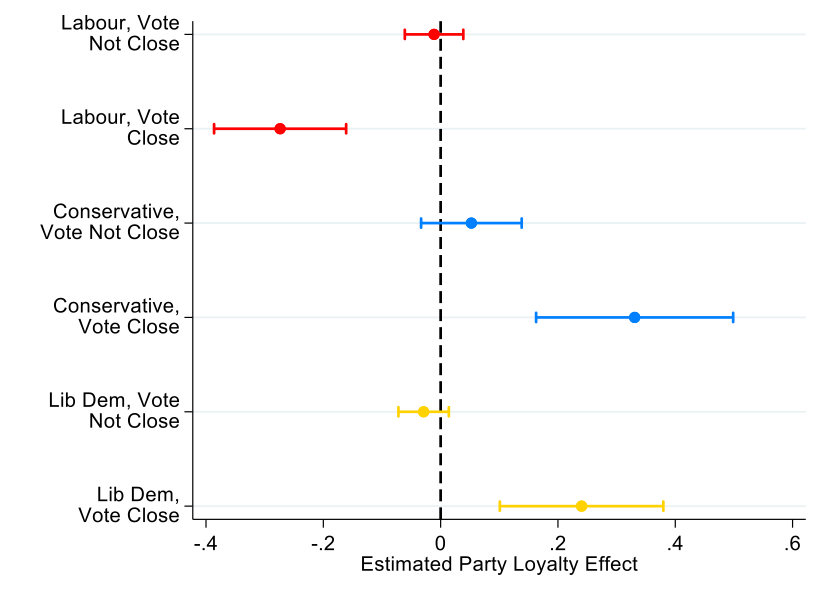

Figure 1 presents the predicted effects of each party on probabilities of opposing the HFEA – holding all other variables at their median values at the low and high values (10th and 90th percentiles) of the closeness-of-the-vote variable. On votes where the outcome was assured in advance, the effect of Labour Party affiliation is statistically indistinguishable from zero. On votes with more opposition, Labour affiliation has a stronger, statistically significant effect on MPs’ probabilities of voting to oppose the HFEA – suggesting that Labour MPs’ party loyalties were activated on these divisions more so than on divisions where the outcome was more certain.

Figure 1: Predicted effects of party loyalty on MPs’ probabilities of voting to oppose the HFEA, by party and closeness of the vote

While Conservative MPs were more likely to vote to oppose the HFEA on each division, the estimated effect of Conservative Party loyalty was significantly stronger on divisions where the chances of defeating the government were higher. Net of Liberal Democrats’ personal support for most of this legislation, Figure 1 shows that a similar effect could be seen among Liberal Democrat MPs. This suggests that Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs were particularly motivated by party loyalties to vote en bloc to try to embarrass the (Labour) government when the outcome of the vote was less certain.

Context and party loyalties

While these results should only be viewed as a first test of the argument, they nonetheless suggest that the impact of party loyalty on MPs’ voting behaviour is shaped by the partisan context surrounding the vote. When divisions are foregone conclusions, MPs may feel free to deviate from the rest of their party and vote their personal convictions, as this is of little consequence for their party. But when the vote is likely to be close, MPs may feel pressured to rally to their party’s defence – even if it means voting against one’s personal preferences. If this finding proves genuine in future tests, it has obvious implications for understanding party unity in parliaments, not least being that parties may rely on such loyalties to pass their agendas – particularly when the threat of sanction breaks down (for example with votes on Brexit and Heathrow).

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit. It draws on his article ‘Simply a matter of context? Partisan contexts and party loyalties on free votes’, published in the British Journal of International Relations.

About the author

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.