How the Treasury Committee has developed since 1997

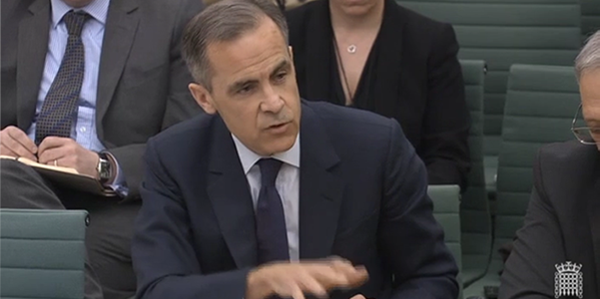

A close analysis of the Treasury Committee’s recent history shows how it has become a successful example of a House of Commons select committee. It has developed a broad remit for scrutinising high-profile figures and institutions in the financial sector beyond the Treasury department, particularly in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, writes Saskia Rombach.  Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, at the Treasury Select Committee. Picture: Parliament UK/Parliament TV, via Parliamentary Copyright

Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, at the Treasury Select Committee. Picture: Parliament UK/Parliament TV, via Parliamentary Copyright

The UK Parliament’s select committee system was set up in 1979. For the first decades of their existence the committees were seen pretty much as a parliamentary backwater. They had little influence over government decisions, or debate in the House of Commons. But more recent years have seen a something of a minor revolution.

Since 2005, select committees have increasingly established more enquiries and have tackled a broader range of topics. When the committees were set up, they were given the task of shadowing ministerial departments and examining their ‘expenditure, administration and policy’. However, there is no specific text in the standing order that limits the committees to these subjects of enquiry. Over time, select committees have used this flexibility to look at topics that interested them or felt relevant to their purpose, and to support debate in the House of Commons. Research shows this widening of committee interests has been accompanied by a rise in Committee report success rate: a larger percentage of policy recommendations have been accepted by the government, either after a back and forth with a select committee, or without debate.

In a recent article, I looked at the particular trajectory of one committee, the Treasury Committee, and what it took to become the high-profile platform within Parliament that it is today.

In 1997, the Bank of England (Bank) was given new responsibilities for UK monetary policy. It took on the operational task of setting the national interest rates, with the government continuing to set national targets. With this independence, the Bank became a powerful quasi-independent institution. Gordon Brown, Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, noted that many of the architectural plans for the internal division of the Bank’s new powers had been recommended beforehand by the Treasury Committee and suggested an enhanced role for the Committee in examining the Bank Monetary Policy Committee’s (MPC) performance.

Independence for the Bank gave the Treasury Committee the opportunity to venture beyond its initial remit of just departmental review. It now added to the pre-amble of its terms of reference, indicating that it interpreted its remit as not only covering the departments responsible to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, but also organisations such as the Bank and the Financial Services Authority (FSA). This was a meaningful statement. Select committees had previously mainly served as a lobbying platform for quangos seeking to influence legislation, but now the Treasury Committee started to take a more critical view of these institutions beyond parliament.

In the early 2000s, the Treasury Committee set out a demanding programme of hearings that addressed different aspects of financial services regulation. This activity started to attract the attention of outside pressure groups, such as victims of mis-selling by the mortgage, pensions and insurance industries. These groups were looking for a public platform to hold to account the big beasts of the financial world for their actions.

For a few years, the Treasury Committee independently took up investigations into standards of practice of the UK’s banks. In 2005 it looked at ATMs, and how some high-charging machines were placed in more impoverished areas. The resulting investigation changed the way banks thought about and deployed cash machines. Later, the Treasury Committee brought gaps in industry standards to the attention of the FSA, such as a lack of consumer information on high personal debt. This paved the way for the committee to become more embedded in the world of financial regulation policy. The watershed came with the 2008 crisis. Starting with the failure of Northern Rock, the Treasury Committee focused its attention on financial regulatory review and reform. This started off with an inquiry into the fitness of the Tripartite – an agreement between the Bank, the FSA and the Treasury.

The Treasury Committee took up enquiries into several of the banks that failed during the 2008 crisis, and whilst doing so employed new ways in which to gather and process evidence and witness statements. When witness sessions where held with Northern Rock and the banks RBS (Royal Bank of Scotland) and HBOS, the committee worked hard to get their CEOs and all the key players in one room together, chasing down individuals to an almost literal extent. These hearings, which were extensively covered by the media, contributed to the Treasury Committee’s sense that it was accountable to a wider public.

As its remit expanded, the Treasury Committee gained some formal powers which now serve to leverage its influence against the quangos. These include the right to pre-appointment hearings with members of the MPC and the ability to veto the dismissal of the chair of the Office of Budget Responsibility. Oversight of quangos has become an increasingly relevant task for select committees. Since the 1990s, the number of quangos in the UK has grown. Almost all areas of public policy now have specialised, privatised institutions delivering government services. The Treasury is no exception to this. The government takes comfort in the idea of delegating decisions to institutions that have the know-how to stay on top of the banking industry. But quangos are still partly private – and for profit – organisations, and cannot be considered as completely objective in their decision making. As Andrew Tyrie, Treasury Committee Chair between 2010 and 2017, noted: ‘The scrutiny of select committees may be all that there is to protect the wider public interest from poor decisions or low standards of quangos’ behaviour.’.

The Treasury Committee, now under the leadership of Tyrie’s successor, Conservative MP for Loughborough Nicky Morgan, continues in this role today, and is currently looking into RBS and Global Restructuring Group’s mishandling of small- and medium-sized business customers, as well as monitoring the FCA (Financial Conduct Authority)’s progress on its inquiry of the bank’s conduct. The Treasury Committee has come a long way and is likely to remain a strong voice in the House of Commons, confident in holding both government departments as well as quangos to public account.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s article, ‘The Development of the Treasury Select Committee 1995–2015’, published in Parliamentary Affairs.

About the author

Saskia Rombach graduated from King’s College London with an MA in Politics and Contemporary History.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.