How democratic are the UK’s political parties and party system?

For our 2018 Audit of UK Democracy, Patrick Dunleavy and Sean Kippin examine how democratic the UK’s party system and political parties are. Parties often attract criticism from those outside their ranks, but they have multiple, complex roles to play in any liberal democratic society. The UK’s system has many strengths, but also key weaknesses, where meaningful reform could realistically take place.

General election, 2017. Pictures: HM Government, via an Open Government licence (left); Sophie Brown via a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence/Wikimedia Commons (right)

What does democracy require for political parties and a party system?

Parties (and now other forms of ‘election fighting organisation’, like referendum campaigns) are diverse, so four kinds of democratic evaluation criteria are needed:

(i) Structuring competition and engagement

- The party system should provide citizens with a framework for simplifying and organising political ideas and discourses, providing coherent packages of policy proposals, so as to sustain vigorous and effective electoral competition between rival teams.

- Parties should provide enduring brands, able to sustain the engagement and trust of most citizens over long periods. Because they endure through time, parties should behave responsibly, knowing that citizens can hold them effectively to account in future.

- Main parties should help to recruit, socialise, select and promote talented individuals into elected public office, ranging from local council to national government levels.

- Party groups inside elected legislatures (such as MPs or councillors), and elites and members in the party’s extra-parliamentary organisation, should help to sustain viable and accountable leadership teams. They should also be important channels for the scrutiny of public policies and the elected leadership’s conduct in office and behaviour in the public interest.

(ii) Representing civil society

- The party system should be reasonably inclusive, covering a broad range of interests and views in civil society. Parties should not exclude or discriminate against people on the basis of gender, ethnicity or other characteristics.

- Citizens should be able to form and grow new political parties easily, without encountering onerous or artificial official barriers privileging existing, established or incumbent parties.

- Party activities should be regulated independently by impartial officials and agencies, so as to prevent self-serving protection of existing incumbents.

(iii) Internal party democracy and transparency

- Long-established parties inevitably accumulate discretionary political power in the exercise of their functions. This creates some citizen dependencies upon them and always has ‘oligopolistic’ effects in restricting political competition (for example, concentrating funding and advertising/campaign capabilities in main parties). To compensate, the internal leadership of parties and their processes for setting policies should be responsive to a wide membership, one that is open and easy to join.

- Leadership selection and the setting of main policies should operate democratically and transparently to members and other groupings inside the party (such as party MPs or members of legislatures). Independent regulation should ensure that parties stick both to their rule books and to public interest practices.

(iv) Political finance

- Parties should be able to raise substantial political funding of their own, but subject to independent regulation to ensure that effective electoral competition is not undermined by inequities of funding

- Individuals, organisations or interests providing large donations to parties or other ‘election fighting organisations’ (such as referendum campaigns) must not gain enhanced or differential influence over public policies, or the allocation of social prestige (such as honours).

- All donations must be fully transparent, and without payments from ‘front’ organisations or foreign sources. The size of individual contributions should be capped where they raise doubts of undue influence.

Recent developments: the party system

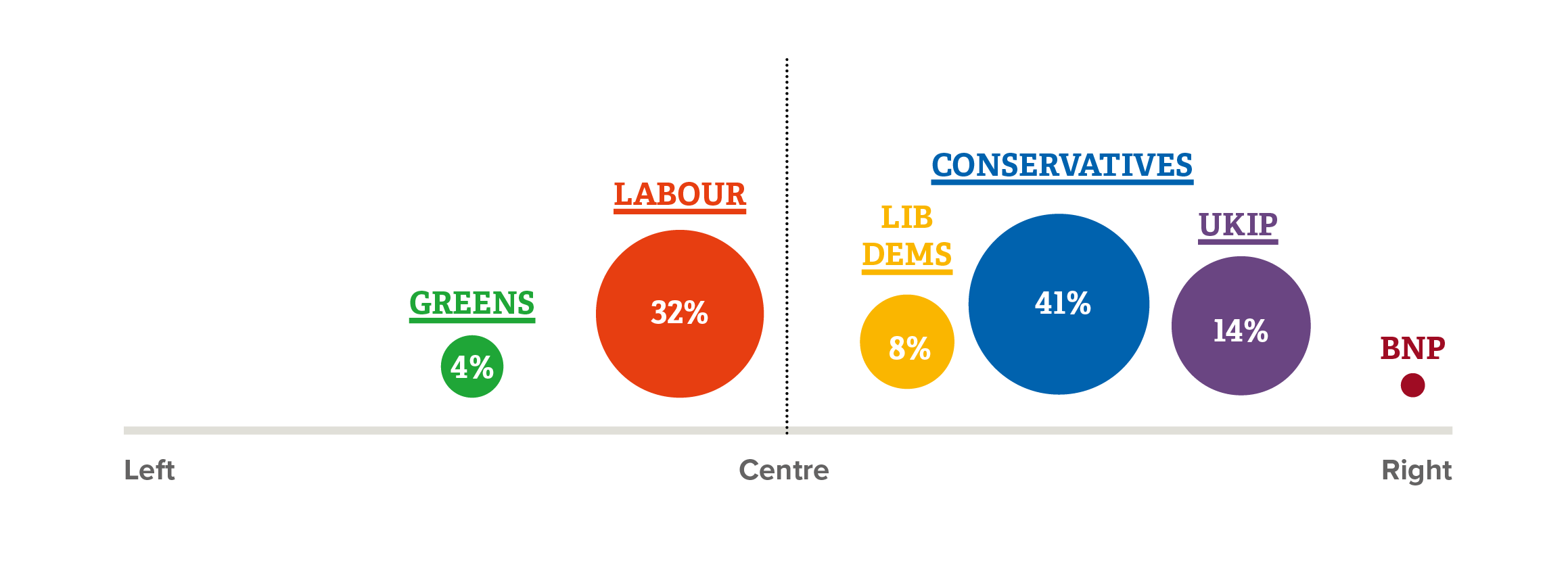

Political parties in the UK are normally stable organisations. Their vote shares and party membership levels typically alter only moderately from one period to the next. But since 2014, party fortunes have changed radically in the UK, particularly in England and Scotland. In 2017 the top two parties secured more than four-fifths of votes in the UK (Figure 2), whereas in England (their ‘home ground’) their share was 73% only two years earlier (Figure 1). With the Brexit referendum won for ‘Leave’ in 2016 and its party leadership in chaos without its former leader Nigel Farage, the UK Independence Party’s (UKIP’s) support in England in 2017 plummeted to 2% – whereas two years earlier they commanded one in seven English votes at the general election (and their opinion poll ratings were higher). Already in 2015, the Liberal Democrats’ vote share had fallen sharply to just 8% in England (and lower elsewhere), around a third of its 2010 level – as the electors punished them for their 2010–15 ‘austerity’ coalition government with the Tories. In 2017 their support still languished, although in local council elections in 2017 and 2018 they secured around one in six votes.

Yet the most fundamental difference in the UK party systems between the elections arose from the Brexit referendum in June 2016. Figure 1 below shows that in 2015 the competition space of British politics was still essentially one-dimensional – so that parties could still be organised on a classical left-right dimension, with the left standing for more public-sector spending and egalitarian policies, and the right standing for free-market solutions, less welfare spending and stronger policies on restricting immigration. There was a pro- and anti-European Union dimension in British politics in 2015 but only UKIP, with their advocacy of EU withdrawal, placed it centre stage. For the rest the issue was sublimated, with the Cameron-led Conservatives and Miliband-led Labour both offering very similar and quite consensual-seeming ‘European’ policy positions. Inside the Tories, although strong currents of Euroscepticism were beginning to predominate again behind the scenes, this issue hardly featured in Cameron’s 2015 campaign.

Figure 1: The party system in England, in the May 2015 general election

Source: P. Dunleavy, 2017 Lecture.

Source: P. Dunleavy, 2017 Lecture.

Notes: The positions of party ‘circles’ show their approximate left/right position; the size of the circles shows indicates their vote shares in England. Parties with names underlined won seats.

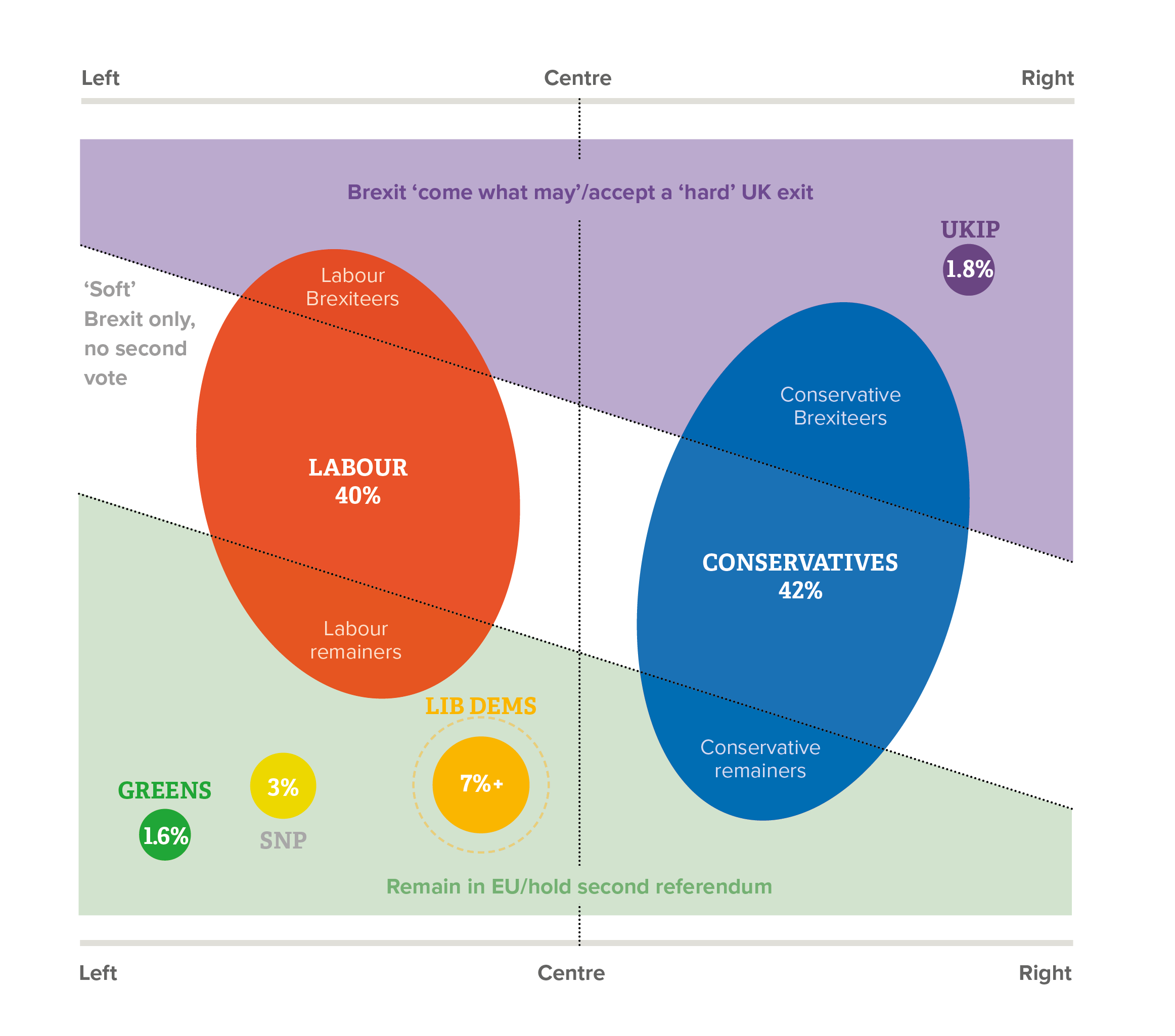

By 2017, Figure 2 shows that a year after the shock June 2016 referendum vote for ‘Leave’ the space of party competition was clearly two-dimensional, with the left-right ideological spectrum now cross-cut slantwise by a three-fold cleavage between:

- Strong Eurosceptics committed to implementing the ‘Leave’ vote, whatever the consequences, perhaps even walking away from the EU with a ‘no deal’ outcome – shown in the purple-shaded area.

- Strong ‘Remainers’ committed to retaining the closest possible relationship with or full customs union and single market access to the EU, and perhaps to holding a second referendum for the public to approve the detailed outcome of withdrawal negotiations – shown in the green shaded area. Significant sections of public and elite opinion here were also willing to see the 2016 vote reversed if possible.

- In between, in the unshaded area, lie the largest blocs of elite and public opinion, committed to implementing the ‘Leave’ vote so that ‘Brexit means Brexit’ as May insisted, but also seeking the best possible compromise outcome for the UK in retaining links to the EU while yet not having to accept ‘freedom of movement’ of EU citizens into the UK, or any EU policies, or jurisdiction by the European Court of Justice.

Figure 2: The UK’s changed party system at the 2017 general election and the subsequent Brexit negotiations phase

Source: P. Dunleavy, 2017 Lecture.

Source: P. Dunleavy, 2017 Lecture.

Notes: The positions of party circles show their approximate left/right position; the size shows their vote shares at the 2017 general election. The dotted line around the Liberal Democrats indicates their approximate level of support in 2017 and 2018 local elections (16%, calculated using the BBC’s national equivalent votes share measure).

These pro- and anti-Brexit lines of cleavage affect both the main parties. There are more Conservative ultra-Leavers and more Labour strong Remainers, but both the top two parties are internally divided into the three groups above. Only the Liberal Democrats, Scottish National Party (SNP), and the Greens came out fully for remaining in the EU or as close as possible, while the now-diminished UKIP was equally clearly for leaving ‘come what may’. The divisions within the main parties meant that although Theresa May called the snap 2017 election supposedly to strengthen her bargaining hand in negotiations with Brussels, in fact the EU withdrawal issue was again handled in a ‘sub voce’ manner by both Conservatives and especially Labour – whose policy position concentrated on domestic issues and remained deliberately very vague on European issues.

A succession of parliamentary votes on Brexit legislation in 2017 and 2018 has so far only confirmed the picture in Figure 2, with Labour’s position varying quite markedly depending on the detailed wording of each vote. Significant numbers of Conservatives have voted against the May government’s ‘shaky compromise’ strategies at various stages, while many Labour MPs in strong Leave-voting constituencies have supported the government against their party line on occasion (while others, particularly London MPs, have rebelled for pro-EU amendments). Jeremy Corbyn has especially kept Labour’s policy line so subtly modulated as to be almost invisible outside Parliament itself.

So British party politics has never in recent history been so complex, and party labels have rarely been so little use in predicting how people stand on the dominant issue facing the UK. At the same time the successive ‘suicide’ decisions of the Liberal Democrats (in 2010–15, by backing the Cameron-Clegg coalition government and implementing austerity policies for five years) and of UKIP (by losing Nigel Farage as leader at the height of the party’s Brexit success, and being unable to replace him in any coherent way) have boosted the Conservative-Labour dominance of the political process. The apparent two-party predominance broadly endured in opinion polls into mid-2018 raising questions about whether the UK (or at least England) has decisively shifted back in love with ‘two-party’ competition? Or will multi-partism survive (as it clearly has at local level) and grow back once the stress of Brexit decisions eases?

Recent developments: inside the parties

Labour: In the extended 2017 election campaign Jeremy Corbyn reversed a 20 percentage point deficit in the opinion polls at the outset, thanks to a growth in younger supporters and sophisticated online campaigning. Aided by May’s campaign misfiring, his leadership produced an unprecedented 10 percentage point growth in Labour’s vote share over six weeks.

This performance cemented Corbyn’s leadership and the policy changes that he had implemented, shifting the Labour Party decisively leftwards in opposition to austerity cuts; and contemplating re-extending public ownership again for the railways, water and perhaps other industries. He maintained support for implementing the 2016 Brexit vote, while successfully masking or finessing this stance with pro-Remain supporters (not least amongst the young). His triumph came after two torpid years. In summer 2015 Corbyn was only just allowed to stand for the leadership at all by the naïve generosity of some centrist MPs in getting him 15% of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) signatures. His runaway victory, with over three-fifths support amongst the party’s newly enlarged membership, was greeted with horror by the PLP’s centre-right, but showed how astonishingly out of touch most Labour MPs had got from their activists. In summer 2016 Corbyn’s perceived failure to campaign overtly enough for Remain was the trigger for four-fifths of his shadow cabinet to resign, triggering another leadership election. Yet the attempted coup was almost farcically mis-handled. No viable alternative candidate had been identified in advance, and an attempt to make Corbyn re-gather nominations from 15% of MPs before he could stand again also failed. He subsequently romped home with 62% support from members, against a lacklustre and previously unknown centrist candidate, Owen Smith.

At long last the PLP had to accept his leadership, and Corbyn and his MPs held their nerve when May called a snap election. They gave her the two-thirds consent of the Commons that she needed under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, despite lagging Labour badly in the polls. The process for defining a Labour manifesto then worked well, producing a popular document with few hostages to fortune. And in the aftermath of the narrow 2017 defeat, Corbyn steered a rule change through the party’s National Executive lowering the PLP nominations bar to 10% of MPs, so ensuring that a future left candidacy for the leadership should be feasible. Most of the new MPs in 2017 are Corbynites, the shadow cabinet has worked well (despite Labour’s evasiveness on Brexit), and Labour’s poll ratings have broadly tied with the government’s into summer 2018. The alleged influence of Momentum, a parallel movement of Labour supporters, has not so far produced clear evidence of far-left ‘entryism’, and threats to sitting MPs from the left have been relatively few.

On another front Corbyn has faced strong and vocal criticism by UK Jewish organisations that Labour has failed to crack down on anti-semitism within its ranks. An official Labour report found that the problem was small scale. And the NEC subsequently took actions to strengthen disciplinary penalties for members breaching the party’s code of conduct – whose most prominent casualty included former London mayor Ken Livingstone, who resigned from the party in spring 2018 over the issue. The party’s vulnerability to attack here reflects three factors: the re-growth of the Labour left (who condemn the illegal permanent Israeli occupation of territories seized after the 1967 war); Corbyn’s identification with this position, and Labour’s remodelling itself as a multi-ethnic urban party. The PLP has demanded a stronger definition of anti-semitism in the code of conduct. However, the party’s defenders argue that the pro-Israel lobby in the UK systematically categorises every criticism of that state as anti-semitism, normally without any evidence of prejudice against Jews as a race having been expressed – in order to close down criticism of Israeli repressive actions against Palestinians.

Conservatives: The party under Theresa May also increased their 2017 vote share, reaping a dividend from UKIP’s collapse. Yet this was not enough to retain a Commons majority against the Labour surge, nor to save May’s legitimacy with her party for ‘wasting’ David Cameron’s (small) 2015 majority. May became a party leader and prime minister on notice, with an expectation that at some point she would be superseded, either by resigning or by a leadership contest being triggered. Her original accession in 2016 (with only an aborted election, from which all other candidate fell away) turned into a liability when May proved an uncharismatic (allegedly ‘robotic’) performer on the campaign trail. And her two top aides were widely blamed for mishandling a 2017 manifesto pledge on taxing the elderly to fund social care, resulting in their subsequent speedy departure.

May also faced a difficult task of party management over its Brexit strategy, which constantly plagued her during her first two years in office. She ensured that Brexiteers formed a third of her cabinet, gave them some key negotiating roles (notably David Davis, supposedly in charge of negotiations) and brought her main erstwhile rival for the leadership, Boris Johnson, into the cabinet in the (deliberately?) inappropriate role of foreign secretary. In July 2018, she forced a long-delayed confrontation over the UK’s Brexit negotiating position with the Brexiteers in the cabinet at a Chequers awayday, only to see Johnson and Davis both resign two days later and a guerrilla war escalate in Parliament with her large group of Brexiteer MPs.

The Conservative’s key problem is that both wings of the party have suffered cataclysmic defeats in intra-party battles in living memory, which were so fundamental for both sides that maintaining the Tories’ famous capacity to coalesce under pressure has become very difficult. For the right, the 1990 ejection of Margaret Thatcher from the leadership by the pro-European centre-left created a ‘stab-in-the-back’ myth that fuelled a bitter Euroscepticism that grew and became more intense over nearly three decades. For the centre-left, the Brexit Leave vote became a symmetrical disaster, causing the consequent ejection of David Cameron (and his Chancellor/heir apparent George Osborne) from Downing Street. The Tory right’s role here was one Remainers find equally hard to forgive – reversing as it does 43 years of centre-left policies on the EU.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Britain’s party system is stable, and the main parties generally provide coherent platforms consistent with their ‘brand’ and ‘image’, despite the party cleavages caused by the Brexit issue (see above). | Party membership in the UK has increased from a low base in 2010, but it is still low. Around 950,000 people are party members, out of a population of 65.6 million, with Labour and the SNP both showing strong recent growth. Conservative membership is now perhaps the most elderly of all the parties and remains small relative to Labour’s renewed mass membership. |

| Britain’s political parties continue to attract competent and talented individuals to run for office. | Plurality rule elections privilege established major parties with strong ‘safe seat’ bastions of support, at the expense of new entrants. The most active political competition thus tends to be focused on a minority of around 120 marginal seats, with policies tailored to appeal to the voters therein. |

| Entry conditions vary somewhat by party, but it is not difficult or arduous to join and influence the UK’s political parties. Labour initially opened up the choice of their top two leadership positions to a wider electorate using their existing trade union networks and a £3 ‘supporter’ scheme (in 2015), but later reverted to full members only voting, after tensions with the party’s MPs. | It is fairly simple to form new political parties in the UK, but funding nomination fees for Westminster elections is still costly. And in plurality rule elections new parties with millions of votes may still win no seats, as happened to UKIP in 2015. At local level, some one-party dominant areas also produce councils with no opposition councillors at all. |

| All the main parties (except perhaps UKIP) have recruited across ethnic boundaries, helping to foster the integration of black and ethnic minority groups into the mainstream of UK politics. | Labour has had long-running difficulties with allegations of anti-semitism amongst some party members in recent years (see above). Some critics argue that the Conservatives have failed to tackle Islamophobia within their ranks. |

| Labour has involved a wider set of ‘supporters’ in its affairs and used digital campaigning more. And the separate group Momentum has helped channel back disillusioned, left-leaning people who had left the party under Blair and Brown, and younger people into ‘parallel’ Labour involvements through both ‘clicktivist’ and more ‘old school’ activism. | Most mechanisms of internal democracy have accorded little influence to their party memberships beyond choosing the winner in leadership elections. Jeremy Corbyn claims to be counteracting this and listening more to his members. However, in consequence, Labour struggled to delineate the relationship between MPs in the parliamentary party (who MPs saw as not answerable to voters) and the enlarged membership (who may not reflect Labour voters’ views well). These tensions eased in 2017. |

| The UK’s main political parties are not over-reliant on state subsidies and can generally finance themselves either through private membership fees, individual donation and corporate donations, or (in Labour’s case) trade unions funding. | There are large inequities in political finance available to parties, with some key aspects left unregulated. These may distort political (if not) electoral competition. Majority governments can alter party funding rules in directly partisan and adversarial ways (see below). |

| In the restricted areas where it can regulate the parties, the Electoral Commission is independent from day-to-day partisan interference. | The ‘professionalisation of politics’ is widely seen as having ‘squeezed out’ other people with a developed background outside of politics (but see below). |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| Before the 2016 Brexit vote the UK seemed to be historically evolving towards multi-party politics, a trend that also found expression in elections beyond Westminster and English local government. New and ‘outsider’ parties strengthened anti-oligopoly tendencies. Since then, however, public opinion showed a renewed emphasis upon top two-party competition. | Critics argue that the cross-cutting of both the top two parties by Brexit positions shown in Figure 2 above means that party labels and identities are no longer effectively structuring (but instead obscuring) the dominant issues in UK politics. |

| Some strong ‘new party’ trends have emerged towards broadening involvements using digital means and extended outreach/lowered barriers to membership within Labour and the SNP. These developments could strengthen party ties with civil society, reversing years of weakening. Alternatively these effects may ebb away again (see below). | In multi-party conditions, plurality rule elections for Westminster may operate in ever more eccentric or dramatic ways, as with the SNP’s 2015 landslide in Scotland almost obliterating every other party’s MPs there. The SNP’s strong support in 2014–16 threatened to create a ‘dominant party system’ system in Scotland, where party alternation in government ceases for a long period. However, this prospect soon receded with both Tory and Labour revivals north of the border. |

| Digital changes also open up new ways in which parties can connect to supporters beyond their formal memberships and increase their links to and engagement with a wider range of voters. Parties now generally conduct their leadership elections using an online system which makes it easier to register a preference. Other matters of internal party business and campaigns could soon be affected, potentially including setting policy. | The growth of political populism and identity divisions post-EU referendum has ‘hollowed out’ the centre ground of British politics, with the Liberal Democrats unable to regain their earlier momentum. |

| The advent of far greater ‘citizen vigilance’ operating via the web and social media like Twitter and Facebook creates a new and far more intensive ‘public gaze’ scrutinising parties’ internal operations. Tools such as ‘voting advice’ application apps or the Democratic Dashboard also allow voters to access reliable information about elections and democracy in their area – information that neither government nor the top parties has so far either been able or willing to provide. | Moves by governing political parties to alter laws, rules and regulations so as to skew future political competition and disadvantage their rivals can set dangerous precedents that degrade the quality of democracy. The Conservative government changes to electoral registration and redrawing of constituency boundaries may all have such effects, even if implemented in non-partisan ways. |

| All the UK’s different legislatures (Westminster, and the devolved assemblies/parliaments in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and London) have now sustained coalition governments of different political stripes and at different periods, and each has operated stably. Therefore, the UK’s adversarial political culture does not rule out cross-party cooperation where electoral outcomes make it necessary. |

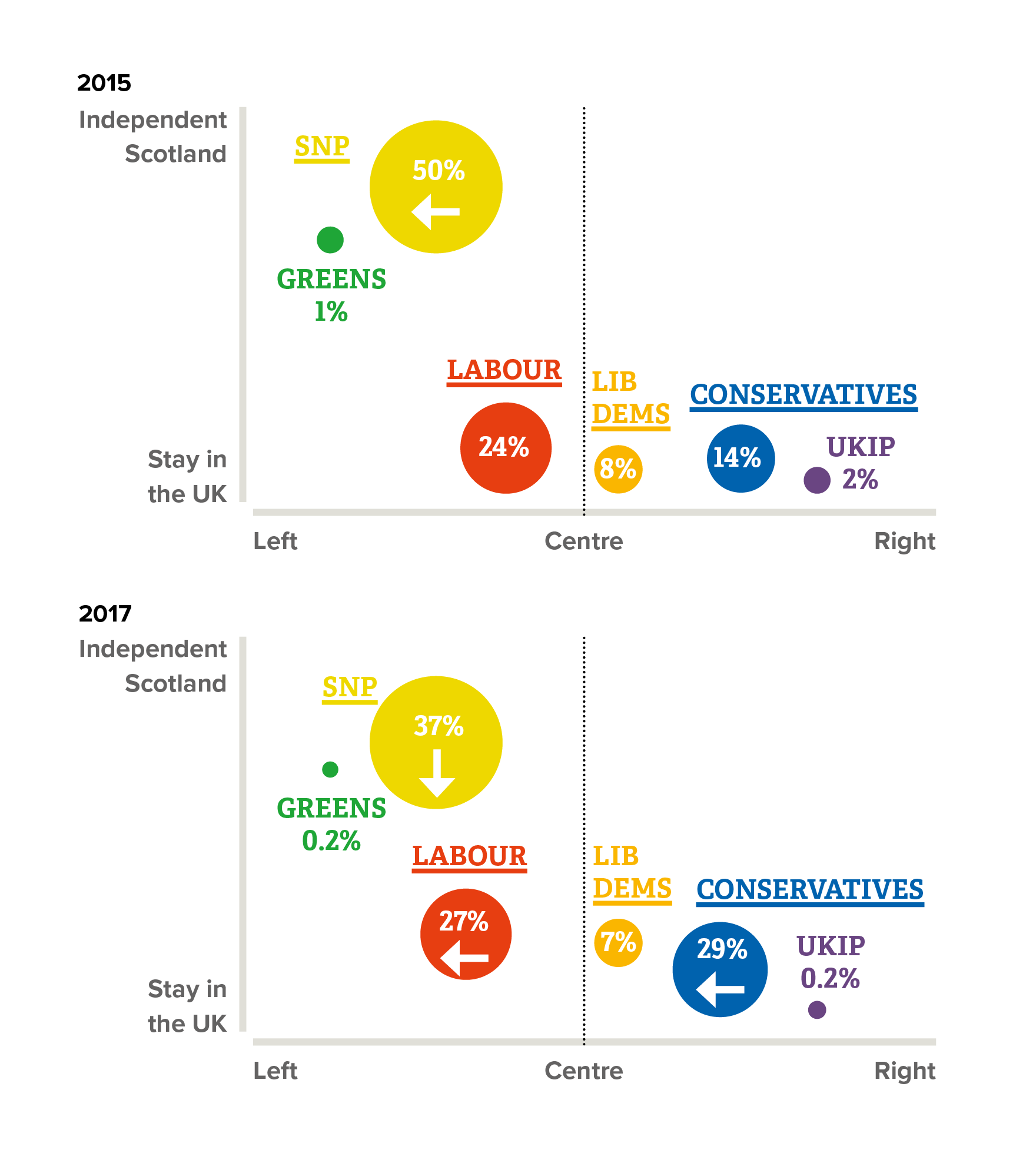

Changes in the Scottish party system

By contrast to England, and to a large extent Wales also, in Scotland politics has long operated across two ideological dimensions, with left/right cleavages cross-cut by another issue of equal (sometimes greater) salience: should Scotland stay in the UK, or not? And how much power should be devolved to Edinburgh? Following the extraordinary mobilisation around the 2014 independence referendum (which was narrowly lost by 55 to 45%) this line of cleavage greatly benefited the SNP (and the Scottish Greens in a much smaller way). It tended to undermine and push together the other four parties, all of which campaigned to keep the union with the UK.

Despite their ’Indy’ referendum defeat the SNP’s enhanced membership and morale meant that by the time of the 2015 general election they gained a pre-eminence as the ‘voice for Scotland’ against the prospect of a clear majority Tory UK government, as shown in Figure 3a. Gaining half of all Scottish votes in 2015, they won all but three of the country’s 59 seats, leaving Labour’s traditional dominance of Scottish representation in the UK Parliament shattered with just one MP, the same number gained by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. For a time, it looked as if the SNP would exert a hard-to-challenge dominance in Scottish politics, controlling as they did both the Scottish government in Edinburgh, a majority of all MSPs and almost all Scottish representation at Westminster, against a multiply-divided opposition.

Figure 3: The Scottish party system at the 2015 and 2017 general elections

Source: Dunleavy, LSE Lecture Notes for course Gv311.

Source: Dunleavy, LSE Lecture Notes for course Gv311.

Notes: The size of each party circle indicates its rough size and salience in the party system, and its approximate position in two-dimensional space. The numbers in each circle show that party’s vote share percentage in Scotland. Parties with names underlined won seats.

In the 2016 Scottish Parliament elections, however, the SNP as incumbents lost a little ground in votes (down to 42%, and 63 of 129 seats), while the Tories jumped nearly 11% to become the main opposition on 23% support, and Labour fell back badly to third. The Liberal Democrats were unchanged, but the Greens moved from 2 to 6 seats, becoming critical for the SNP staying in power. Nicola Sturgeon looked to have four more years as First Minister, and when Scotland voted by 62 to 38% not to leave the European Union, her allies quickly raised the prospect of holding a second referendum on independence far more speedily than anyone had previously envisaged – not least to resist a Westminster ‘land grab’ for EU powers that the SNP argued could permanently reset the devolution settlement in the UK’s favour.

By 2017, however, public support for any second independence referendum amongst Scottish voters was clearly a minority view. The new Scottish Conservative leader, Ruth Davidson, moved her party’s position decisively towards the political centre, endorsed more devolution of powers to Scotland, and sharpened criticisms of the SNP’s government at Holyrood. The Tories perhaps attracted more support from pro-union Labour and Liberal Democrat voters as the most viable unionist opposition.

In addition, during the June 2017 election campaign Jeremy Corbyn’s UK national leadership also shifted Labour’s image leftwards, and brought the party back in line with the Scotland’s left-leaning political spectrum. The party also backed more powers for Scotland and slightly blurred its rejection of independence (for instance, no longer making support for independence inconsistent with Labour membership). These changes caused a significant swing back to a multi-party system, shown in Figure 3b above. The later easy victory of Corbynite Richard Leonard as Scottish Labour leader consolidated these changes, although he has yet make much of a mark with voters at large.

The SNP could not sustain its 2015 majority vote share, losing a quarter of its support. Its seats were slashed back from 56 to 35, just under three-fifths of the total of Scotland’s 59 MPs. The scale and speed of these seat reversals was damaging. It was not until spring 2018 that the SNP dared to publicly re-launch the idea of an Indy 2 referendum, at some point after Brexit had occurred, perhaps in 2020 or 2021. The danger of Scotland becoming a ‘dominant party system’ – where the same party is a serial winner against a fragmented opposition incapable of co-operating to defeat it – clearly had receded after 2016.

Structuring competition and party ‘brands’

We noted above that the main alternative dimension in England has been the pro- and anti-EU one, increasingly overlapping in UKIP’s campaigning with anti-immigrant sentiments. The right-wing press have also explicitly played to anti-immigrant views, notably in their Brexit coverage, but officially the Tories have not played along. However, Theresa May’s insistence on maintaining the net immigration target of below 100,000 people a year, which was set under the Cameron government when she was Home Secretary, and which has never been even vaguely approached by actual, much higher migration levels, undoubtedly reflects a sub voce Conservative appeal on the same lines. Attitudes towards immigration are far more aligned with existing left-right cleavages, especially as Labour has developed towards being more of an urban/multicultural party, less dominated by its working class/trade union lineage.

Both the top two British parties have had chronic difficulties in organising around the EU/immigration aspect of politics, maintaining an agreed strategy of not vocally campaigning on immigration, lest it stir up ethnic tensions. As we saw above, Labour has become progressively more pro-EU since Brexit (echoing more the strongly European stances under previous leaders) and the Conservative MPs (if not their leadership) have become more anti-EU and pro-Brexit.

The enduring quality of parties’ appeals is borne out by recent research showing that strong party supporters place themselves ideologically at the same place as the parties they identify with. Supporters tend to accurately perceive their own party’s position, but to see opposing parties as more ‘extreme’ than they are. On the centre-left in 2017 there were multiple overlaps of party supporters’ views amongst Labour, the Greens and Liberal Democrats, while on the right the Conservatives and UKIP overlapped in some anti-EU positions. Yet in mid-terms, between general elections, around two-fifths of those backing major parties told IPSOS-MORI they did not know what they stood for.

So are main parties failing to communicate their brands in a sustained and consistent manner? A potential explanation may lie with the various processes of party ‘modernisation’ that took place over recent years, with each of the three main parties attempting to ‘move to the centre’. The shifts to a more ‘managerialist’ politics of detail that occurred before Corbyn, the EU referendum and May’s realignment of the Tories may have left many voters less clear what each party advocates. But the reconfiguration of British party politics since 2016 now suggests that a realignment of the party system may be in train, with UKIP potentially eliminated altogether, to the Tories’ great benefit.

Electing party leaders, or not

For a brief period in the 2010s, all the parties enacted protracted processes in which their mass memberships would elect the party leaders, albeit from fields of contenders that were initially defined by MPs. Yet some of these arrangements now look as if they are likely to change or fall into abeyance. Jeremy Corbyn’s two commanding party leadership election wins in 2015 and 2016 set him up to almost succeed as a campaigner in the 2017 general election, and the changes lowering the share of MPs needed for nomination (noted above) may guarantee that Labour’s internal elections remain critical for the party in future.

However, in the other two leading parties, the members’ voice has recently been de-activated and leadership competition denied. In June 2016, following Cameron’s shock resignations, complex politicking amongst Tory MPs meant that Boris Johnson did not even make the nomination stage and Michael Gove was ignominiously eliminated at the ‘winnowing out’ second ballot of Tory MPs. The clear frontrunner Theresa May was left facing only the relatively unknown Brexiteer Andrea Leadsom in a run-off vote by party members that would in theory take all summer long. Leadsom withdrew, making May the unelected but initially unquestioned leader. Effectively the Tory MPs’ fix denied their party members any chance to vote.

However, May’s subsequent huge problems as party leader, and her lack of success as a campaigner at the 2017 general election, may mean that the next Tory leadership contest will have to run by the book and involve members after all. The complex politics of precipitating a new contest without seeming to be ‘disloyal’ put many alternative leaders off in 2017–18, especially while May could be left to bear the burden of the Brexit negotiations. But as time wears on, the pressure for a resolution of her perceived ‘caretaker only’ leadership tenure will intensify.

The second party where members effectively lost a vote was the Liberal Democrats. When they came to elect a new leader after their 2015 general election losses their party had only eight MPs left in the Commons to choose from. Tim Farron took the helm in 2015 but made little impact. In 2017 he stood down and the elderly returning MP Vince Cable was the only candidate to replace him. By mid-2018 he had largely failed to improve the party’s lowly opinion poll ratings, perhaps reflecting Cable’s own close involvement in the 2010–15 coalition government. The party’s deputy leader, Jo Swinson, may be the party’s best hope of remaking its image in time for a 2021 general election, by passing the leadership baton to a new gender and generation.

Internal democracy for policy-making

All the parties have moved to greater transparency and openness in their affairs, and have different arrangements for intra-party democracy to periodically set aspects of party policy. Labour’s widening of membership and election of the party’s National Executive Committee by members is the most radical innovation, and has created a left majority under Corbyn.

The remaining parties still operate more orthodox arrangements. In theory, Liberal Democrats have the most internally democratic party, with the federal party and party conference enjoying a pre-eminent role in policy formation. Yet in the coalition period the exigencies of the party being in government seemed to easily negate this nominal influence (as has long been argued to be the case in the top two parties). Conservative Party members have relatively little formal influence over party policy, with key decisions made largely in Cabinet or Shadow Cabinet, and to a lesser degree by the national party machine. At local level, members have more influence, but they rarely challenge sitting MPs. UKIP’s members are not empowered by their party’s constitution, which declares that motions at conference will only be considered as ‘advisory’, rather than binding. The Green Party probably allows its membership the greatest degree of influence over internal policy, but in local government has had to tighten up in the few areas where it has exercised power (such as in Brighton).

Recruiting political elites

The main political parties regularly sustain a steady stream of individuals to run for political office, who can be socialised, selected and promoted into their structures. However, the impression has gained ground that increasingly only candidates with professional, back-office backgrounds are being chosen. In fact, such ‘politics professionals’ make up less than one in six MPs, far lower than popular accounts envisage. However, it is true that: ‘MPs who worked full-time in politics before being elected dominate the top frontbench positions, whilst colleagues whose political experience consisted of being a local councillor tended to remain backbenchers’. So politics professionals within the top parties do tend to dominate media and policy debates.

In terms of wider social diversity, the 2017 parliament is in some ways (notably gender and ethnicity) the most diverse and representative ever. Yet as Campbell et al noted in 2015 (when the same claim was made): ‘To put the progress made in perspective, the UK would need to elect 130 more women and double the current number of black and ethnic minority MPs to make its parliament descriptively representative of the population it serves.’ Just 2% more MPs were women in 2017. The problem is that research continues to shows that all the main parties’ membership is disproportionally white, male, middle aged and middle class, with the problem being most severe for the Conservatives. Against this background achieving sustained and rapid improvements in the recruitment of diverse prospective candidates is tricky to achieve.

Representing civil society

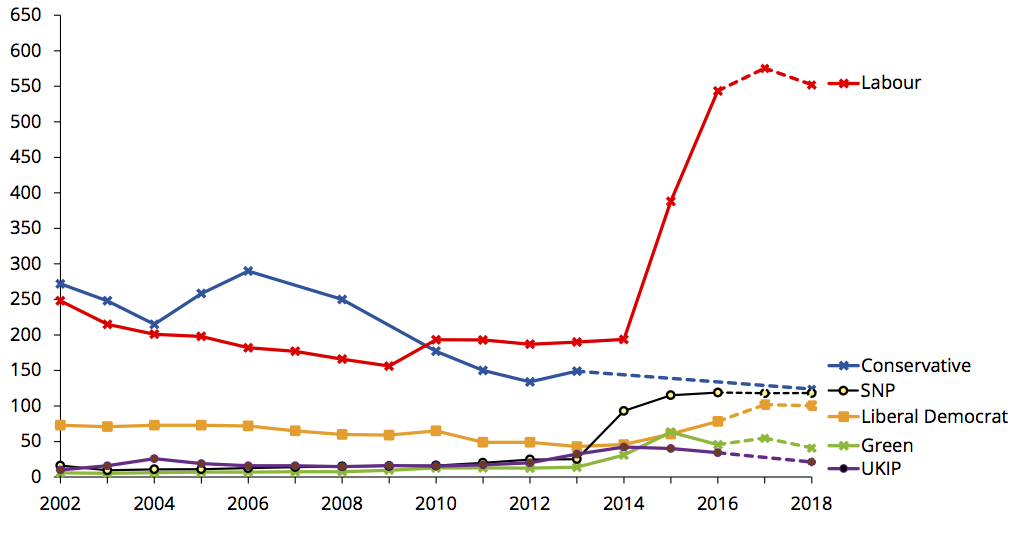

The standard theme of now dated textbook discussions is that the major political parties are declining in their ability to recruit members, and thereby becoming ‘cartel parties’ dependent for their lifeblood upon large donors (such as very rich individuals for all parties, or trade unions with large membership blocs for Labour), or upon state subsidies to parties. Yet Figure 4 shows that this narrative of continuous decline has not been accurate for British parties as a whole in the 21st century.

Figure 4: The membership levels of UK political parties, 2002–18

Source: Lukas Audickas, Noel Dempsey, Richard Keen Membership of Political Parties, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper SN05125, 1 May 2018, p.8.

Notes: The vertical axis here shows thousands of members, from annual accounts submitted to the electoral commission, data from parties’ head offices and, in the case of the Conservatives, media estimates. The Labour party membership numbers of 2015 and 2016 include full party members and affiliated supporters, but not ‘registered supporters’ (who paid only £3). Dotted lines show estimates based on media reports.

The last four years in Figure 4 show soaring numbers of members for the SNP since the independence referendum and of the Labour party since easier membership rules, low cost fees, and the post-general election changes. Some observers point out that now with 522,000 individual members, a Corbyn-led Labour has gained perhaps £8m in annual fees and so may be able to reduce its dependence on affiliated trade unions’ block fee payments – a goal that eluded all previous Labour leaders. The Conservatives also moved against the unions again. The Trade Union Act 2016 introduced an ‘opt-in’ requirement for political levies for new members of trade unions, replacing the previous opt-out provision. This may (gradually) hit Labour’s union income in future years, or it may be mitigated by improvements in union communication practices.

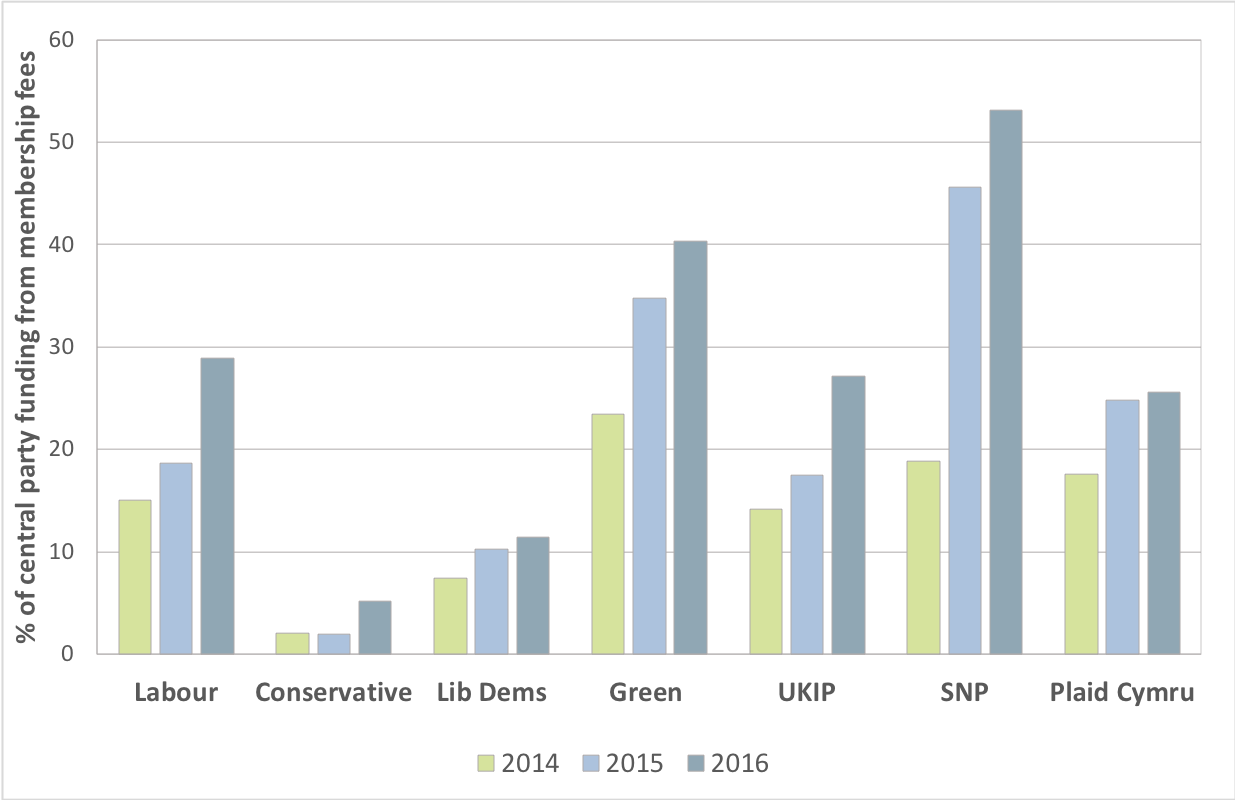

All these changes mean that parties now draw very different proportions of their income from membership subscriptions. Figure 5 shows that the Greens and SNP are the parties for whom membership fees count most as a source of income, with the Conservatives bottom, and the Liberal Democrats nearby at the bottom. Labour, Plaid Cymru and UKIP are in the intermediate group.

Figure 5: Income from membership revenues as a percentage of total income

Source: Party annual accounts submitted to the Electoral Commission

In some European countries, a recent rejuvenation of party politics has taken two contrasting forms. Some new left parties committed to a different kind of ‘close to civil society’ politics emerged on the left (like Podemos in Spain) and Syriza in Greece. More often though populist, anti-EU/anti-immigration parties grew markedly on the radical right. Some observers even discern the ‘death of representative politics’ in such changes. But in the UK the highly insulating plurality rule voting system at Westminster has asymmetrically protected the top two UK parties, with the UKIP wave artificially excluded from Parliament on the right in 2015. And left-of-centre movements have happened not in new parties but within the ranks of Labour (in England) and the SNP (in Scotland). These latter changes have proved resilient so far, but they may still not endure if either party experiences setbacks in future.

Political finance

The core foundations of the UK’s party funding system lie in electoral law. Two key provisions are: (i) the imposition of very restrictive local campaign finance limits on parties and candidates; and (ii) the outlawing of any paid-for broadcast advertising by parties in favour of state-funded and strictly regulated party election broadcasts (set by votes won last time). Opposition parties also have the benefit of a degree of state funding (called ‘Short money’ and again related to votes received) but this is only available to those parties with at least one MP. The bulk of the funds so far has gone to fund the leaders’ offices of Labour, the SNP and Liberal Democrats.

Political finance nonetheless still matters immensely in UK politics because two types of spending are completely uncontrolled, namely: (iii) supra-local campaigning and advertising in the press, billboards, social media and other generic formats; and (iv) general campaign and organisational spending by parties, which is crucial to parties’ abilities to set agendas and create media coverage ‘opportunities’, especially outside the narrowly defined and more media-regulated election periods themselves.

In terms of private donations Figure 5 shows that the Conservative Party gained just over half of the total across the 2013–17 period, mostly from very rich people. Labour, meanwhile, received a smaller 32%, partly from mass membership and trade union fees, with some large individual donations also. The Liberal Democrats, in government until 2015, also gained some large gifts – as did UKIP.

Figure 5: Donations to political parties, 2013–17

| Party | £ millions | % of all donations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total 2013–17 | ||

| Conservatives | 15.9 | 29.2 | 33.2 | 17.5 | 37.1 | 132.9 | 50.5 |

| Labour | 13.3 | 18.7 | 21.5 | 13.9 | 16.1 | 83.5 | 32 |

| Lib Dems | 3.9 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 31.6 | 12 |

| UKIP | 0.67 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 0.65 | 7.4 | 2.8 |

| SNP | 0.04 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 6.5 | 2.5 |

Source: Electoral Commission

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Donating to parties is supposedly transparent. All gifts must be declared and sources made clear, and funding is regulated by the Electoral Commission. But unlike many liberal democracies, there are no maximum size limits on UK donations, although donations from overseas have been clamped down on. Critics argue that ‘the fact that political parties are sustained by just a handful of individuals makes unfair influence a very real possibility even if the reality is a system that is more corruptible than corrupt.’ Close analysis also shows a strong link between donations to political parties and membership of the House of Lords, now almost entirely in the gift of party leaders. Despite supposedly stronger rules applying to ‘good conduct’ in public life (following scandals around 2009). In the past Conservative and Labour leaders have both been very reluctant to give up the lubricating role of the honours system in sustaining their funding hegemony and easing internal party management. The Tories (and Liberal Democrats in a lesser way) continue to take full advantage of this. However, Corbyn has made only two Lords appointments, and the SNP will take no seats there. Meanwhile the Liberal Democrats have far and away the highest ratio of peerages and knighthoods amongst their past MPs of any UK political party.

Although party finance regulation is impartially implemented in a day-to-day manner, there is little to stop a government with a majority from legislating radically to change party finance rules in ‘sectarian’ ways that maximise their own individual party interests and directly damage opponents. In the UK’s ‘unfixed’ constitution, only elite self-restraint, Tory party misgivings or perhaps House of Lords changes (which made a difference to the anti-union law in 2016) can prevent directly partisan manipulation of the opposition’s finances.

Conclusions

The conventional wisdom of ‘parties in decline’ does not now fit the recent history of the UK well, with some membership levels growing, and others fairly stable. Some ‘new party’ trends emerged (for a while) within Labour and the SNP, utilising different, more digital ways of mobilising and stronger links to parts of civil society. Internal party elections of most key candidates (not leaders) are generally stronger now than in earlier decades (except within UKIP). So parties are not yet just the self-serving ‘cartels’ that critics often allege.

Yet many problems remain. The Brexit divide cuts across party lines in an acute way, producing deliberate vagueness in what each of the two top parties say to voters on this crucial issue. The provisions for party members to elect leaders were left unused in the Conservative Party in 2016, and for a time created almost insupportable strains within Labour under Corbyn. The problem of a ‘club ethos’ uniting MPs in the main parties was evident in the over-protection that the Westminster election system grants Conservatives, Labour and now the SNP; in the very partial regulation of political financing and the (only weakly regulated) effective ‘sale’ of honours; in the ability of governments to legislate in sectarian ways to weaken their opposition parties; in weak internal democracy controls or influence over parties’ policy stances and manifestos; and in the sheer scale of parliamentary party remoteness from membership views that can arise.

About the authors

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE, co-director of Democratic Audit and Chair of the Public Policy Group.

Sean Kippin is a PhD candidate and Associate Lecturer at the University of the West of Scotland and a former editor of Democratic Audit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] representing other political parties are captured. Given the complex nature of Britain’s party system, the campaign efforts of parties and candidates beyond the traditional ‘big three’ may become […]

I cant fail to be impressed with such a knowledgable and articulate academic paper. My problem is that it generally does not seem to relate to me as a citizen who feels he has no control over UK politics – effectively disenfranchised. So just a couple of points:

Firstly, your criteria: “Parties should be able to raise substantial political funding of their own,” doesn’t seem to be in the least democratic. Why should the rich have a party that is so well resourced, while the poor do not. It’s rigged.Funding is crucial to campaigning. How much money could a poor person contribute to a party that would represent them? I doubt they could manage £10. So why aren’t donations capped at £10?

Secondly, under “threats”, why is there no mention of the massive effects of micro-targeting and other techniques in social media campaigns? How can this not be brainwashing? It needs really drastic action.

With the greatest respect to both Sean and Prof Dunleavy, please either use the term ‘Great Britain’ rather than ‘UK’, or include the DUP and Sinn Fein.

Thank you.