Campaign spending and voter turnout: does a candidate’s local prominence influence the effect of their spending?

At election time, political candidates in Britain routinely spend significant sums of money on their local campaigns. Generally speaking, the more individual candidates spend, the higher turnout in that constituency. But while some candidates are major contenders in their area, many candidates who are unlikely to win also spend substantial sums on their campaigns. By analysing candidate spending data from the 2010 general election, Siim Trumm, Laura Sudulich and Joshua Townsley find that the money spent by viable contenders has a greater impact on voter turnout than spending by candidates who are unlikely to win.

SNP election campaign. Picture: The SNP, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

SNP election campaign. Picture: The SNP, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

During elections, constituency candidates from all parties and none routinely raise and spend money on their electoral campaigns. This spending covers, among other things, the printing and distribution of leaflets and letters, the use of a local party office and IT resources. In essence, money is spent with the purpose of mobilising voters, and to provide information to voters in the run-up to an election. Unsurprisingly, most studies show that the more candidates spend at election time, the more people vote.

But not all candidates are equal. While some are big players locally – likely to finish first or second place in the constituency – many are not. Is the connection between the amount spent on a campaign and the level of turnout conditional on how ‘viable’ the candidate is locally?

Studies that have compared the effects of spending by different parties have mostly focused on the traditional ‘big three’ parties – Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. But given the rise of other, so-called ‘minor’ parties in recent years – the SNP, Plaid Cymru, Greens and UKIP, among others – local electoral dynamics often involve different combinations of ‘viable’ and ‘less viable’ candidates in different seats.

Consider the marginal seat of Watford in 2010, where the three viable contenders were the usual suspects: Labour, Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. Between them, they secured 94% of all votes cast. Meanwhile, in the Na h-Eileanan an Iar constituency in Scotland, the viable contenders were the SNP, the Scottish Labour Party and an independent candidate, Murdo Murray, who received a combined vote share of 88%.

Instead of focusing on the traditional ‘big three’, we separate the effect of the ‘viable contenders’ in each constituency from the ‘other contenders’ – whichever party they represent. In so doing, we allow for different combinations of ‘viable’ and ‘minor’ candidates in each constituency.

We counted as ‘viable contenders’ those candidates who are in with a realistic chance of winning based on their performance at the previous election. For example, in a safe seat, the only ‘viable contender’ is the party that finished first at the previous election. In two-way and three-way marginal constituencies, the ‘viable contenders’ are the top two and three parties, respectively.

The Ochil and South Perthshire constituency, for instance, was a three-way marginal following the 2005 general election with Labour on 31.4%, SNP on 29.9%, and the Conservatives on 21.5%. In this case, the viable contenders were Labour, SNP and the Conservatives, with the other candidates representing ‘other contenders’. Whereas the conventional approach would only capture the campaign spending of Labour and the Conservatives in this seat, our approach also captures the efforts of the SNP.

Campaign spending and voter turnout

We take the amount spent by candidates in constituencies in Britain, and divide it by the legal spending limit in each constituency. This is because candidate spending in Britain is limited by law and varies according to the size of the electorate and the geography of the constituency. Therefore, we test the impact of relative spending on turnout.

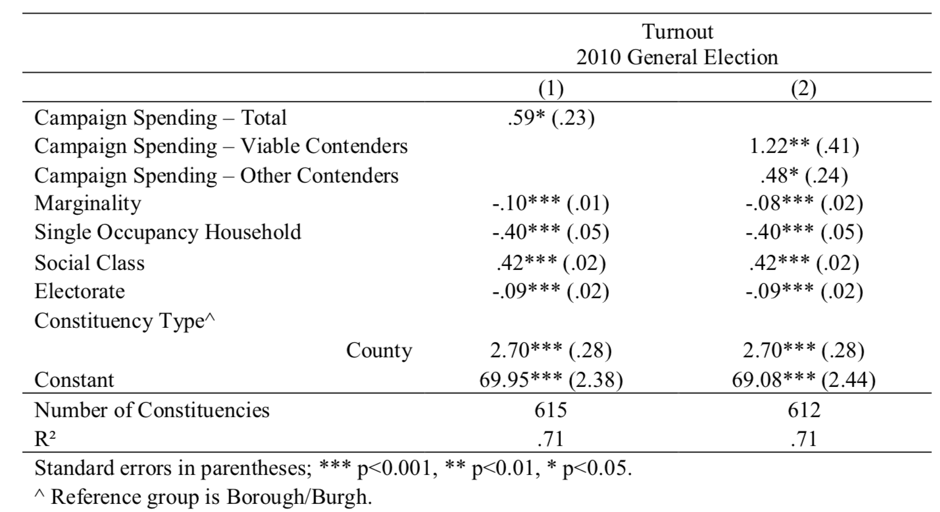

Table 1 presents two regression models, both with voter turnout (%) as the dependent variable. We control for marginality (the bigger the margin of victory, the lower turnout is), and a series of other constituency-level factors that also influence turnout (proportion of single occupancy households, social class, size of the electorate, and whether the constituency is a county or a borough/burgh).

Table 1: Explaining variation in voter turnout with campaign spending

Model 1 shows that the more candidates spend, the higher turnout is in that seat. For every 1 percent that spending (as a proportion of the legal maximum) rises, turnout rises by around 0.6 percent.

Model 2, meanwhile, distinguishes between the spending of ‘viable contenders’ and ‘other contenders’. By separating out the two, we can see that the former has a stronger impact on turnout. When the spending of viable candidates goes up by 1 percent, turnout rises by 1.22 percent. Meanwhile, when the spending of other candidates rises up 1 percent, the associated turnout boost is much lower (0.48 percent).

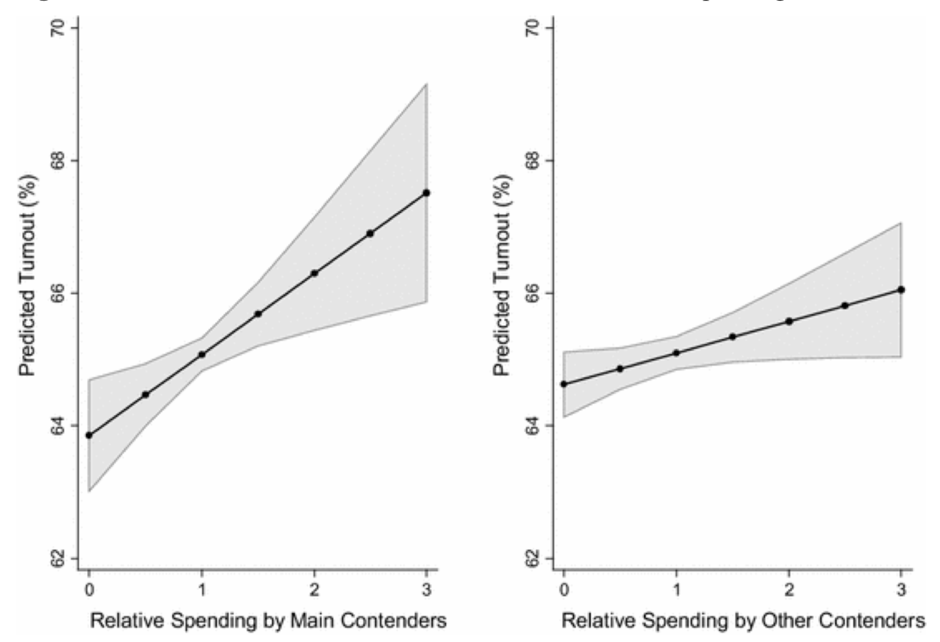

In order to illustrate this, Figure 1 shows the predicted turnout at all levels of campaign spending by viable contenders and other contenders. The difference in the steepness of the lines indicates that the effect associated with spending by viable and other contenders varies notably.

Figure 1: Effect of viable contenders’ and other contenders’ spending on turnout

Conclusion

Campaign spending increases turnout. We show that candidates also differ in their capacity to mobilise voters, according to their prominence in the constituency. When candidates spend more on their local campaigns, the level of participation in that constituency increases – and the higher the local standing of the candidate, the stronger their ability to mobilise voters.

In further analysis presented in the paper, we also find that these effects are not conditioned by how competitive the race is in each constituency. In other words, these mobilising effects are consistent in ‘safe’ constituencies, where the winner is hardly challenged, and in marginal constituencies, where the result is likely to be close.

The study therefore testifies to the relevance of local electoral campaigns when it comes to mobilising voters. We also present a template by which future studies can ensure the substantial sums spent by candidates representing other political parties are captured. Given the complex nature of Britain’s party system, the campaign efforts of parties and candidates beyond the traditional ‘big three’ may become increasingly important.

This article represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

It is based on the authors’ paper, ‘Information effect on voter turnout: How campaign spending mobilises voters’, published in Acta Politica.

About the authors

Siim Trumm is Assistant Professor in Politics at the University of Nottingham. His areas of research include British politics, party politics, parliaments and legislative behaviour, electoral campaigns, and public policy.

Laura Sudulich is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Kent. Her research focuses on electoral campaigns, digital media and voting behaviour, public opinion and the effects of information on political behaviour.

Joshua Townsley is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of Kent. He researches electoral campaigns and political behaviour. Joshua also runs the LSE and Democratic Audit’s Democratic Dashboard voter information project. He tweets @JoshuaTownsley.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Unfortunately this whole argument slightly flounders without considerations of spending that is not counted as spend, but which nonetheless overwhelms the tiny amounts allowed in constituencies. For example, state radio and tv in the Uk – nationally and locally – gives free advertorial style coverage in supposed ‘news’ broadcasts worth millions of pounds to the “main” parties and often uses a distorted version of Orwellian ‘balance’ rules to bar smaller and diverse parties from appearing in these same news and current affairs broadcasts. Political advertising is supposedly banned, but all this means is that the main parties are handed tedious endless ad-ed minutes by the state (in reality, advertising as there is little journalism to it) masquerading as news and current affairs coverage. And the state and main parties then conspire to keep anyone else off the airwaves. Without taking into account these type of massive financial advantages handed to the main parties (dutifully divided up over all the constituencies – it is a cash advantage), you cannot really get a true picture of the impact of the tiny amount spent by those in the constituency within the rules. It is simply overwhelmed and almost irrelevant. On the other side of this argument is the commitment of those marginalised in this way to accessing social media, much of which is outside of the radar of official spending.

You have to ask yourself why UKIP actually grew the way that it did – once it realised before a decade ago that it was effectively barred from access to meaningful tv and radio during campaigns, it focused on social media and online campaigning. It had to until about a decade ago (hence Nigel Farage’s powerful speeches to the EU Parliament were copied on to tens of millions of people while never ever being allowed to actually appear on tv in the UK).

A movement grew in defiance of the state and its broadcast arm and then state radio and tv (BBC and ITV) could not ignore it once it was realised that UKIP probably would (and did) win the 2014 European Elections in the UK. 20k on old fashioned campaigning during an election is, frankly, a sideshow unless what it is used for is designed to be picked up by tv.

The choice of the 2010 election is ironic as it was the last gasp of the old style of elections anyway. Twitter was tiny in the UK in 2009, and by 2015 it was massive. The take-up stats show that only too well. So a few pennies on leaflets might have had a tiny affect still in 2010, but that is all now swept away with what has happened since.No point now spending a few extra grand on headed paper and tired old pizza-style ‘Vote For Me’ leaflets in the constituency of Cumbernauld West Central & Garscadden East with Ecclefechan calling at all stations to Kirkcubright.