Lessons from Ireland’s recent referendums: how deliberation helps inform voters

Ireland’s 2015 referendum on equal marriage and its 2018 one on abortion both had their origins in deliberative assemblies. But did such processes influence the result? The evidence suggests that the information and debate that came with these assemblies had an impact both on vote choice and turnout, writes Jane Suiter.

‘Repeal the 8th’ cookies. Picture: Sebastian Dooris/public domain

‘Repeal the 8th’ cookies. Picture: Sebastian Dooris/public domain

Ireland has made history in recent years with two landmark socially progressive referendum votes on abortion and marriage equality. The votes revealed a growing liberal consensus and generational change in the once conservative Catholic nation; but the votes were also notable for the new deliberative procedures they employed, and which appear to have had an impact on understanding, vote, and turnout.

Referendum research has revealed the importance of voters understanding the issues at stake in driving both turnout and votes in line with attitudes and values. A good deal of the research has focused on Ireland which has a long history of referendums due to a combination of fairly restrictive constitutional provisions for consulting the people and extensive social and political change. These referendums can be classified into three categories: those relating to sovereignty (EU Treaties largely); administrative or technical; and moral or social. It is the latter category which have made the headlines in recent years.

These votes tend to draw from a deep-rooted conservative-liberal cleavage in Irish politics and have delivered some of the divisive and bitter referendums of recent years. Divorce passed by just 9,000 votes in 1995; abortion referendums from the 1980s and until 2002 were noted for the deep hostilities they exposed; a Children’s Right referendum as recently as 2015 passed by just 58–42% on a turnout of just 33.5%, despite almost no opposition. As a result, successive governments were reluctant to hold further referendums on abortion despite calls from the UN and the European Court of Justice. Yet in 2015, marriage equality was passed by a large majority with a high turnout. In 2018, the abortion proposal was passed with an even larger majority on a higher turnout, confounding many analysts who had predicted a narrow victory.

So what had changed in the Republic? Ireland of course was becoming more liberal, partly the result of a generational shift and partly as a result of widespread revulsion at cases of clerical sex abuse in the Catholic Church. But there is another factor: Ireland’s new deliberative assemblies. Both referendums are notable for having their origins in these assemblies and for the extensive campaigns with widespread political and civil society involvement which accompanied them. These national citizen assemblies or constitutional conventions are made up of randomly selected citizens (in the case of the convention one-third are politicians). Experts on both sides give evidence and the members deliberate in small groups voting at the end of the session. In both cases, the attendees voted for a referendum on these issues and in favour of progressive change following deliberation on the evidence.

For many politicians, the initial advantage of stabling these assemblies may have been the passing of responsibility for a contentious issue to citizens. But the assemblies had other advantages. The idea is that deliberation in advance of a referendum can structurally undermine populist rhetoric, increase knowledge levels, and provide a closer match between values and vote choice. Specifically, it is argued that these assemblies can assuage the most common criticism associated with referendums: that they represent ‘the tyranny of the majority’, which is based on voter ignorance and the tendency to vote based on heuristics rather than evidence.

Indeed, we find in both referendums that voters who are familiar with the Convention or Assembly to vote differently from those who are not. This suggests that the establishment of assemblies in advance of the referendum has an impact on the deliberative nature of the referendum in the wider community. In both referendums there is a positive and statistically significant effect on the probability of voting Yes by those who felt they fully understood the issues. Further research to clarify the mechanisms and impact is currently being undertaken by the research team.

Prior to the establishment of these assemblies, information provision was left solely to the Referendum Commission – an independent body that explains the subject matter of referendum proposals, promotes public awareness of a referendum, and encourages the electorate to vote. However, the Referendum Commission cannot and does not provide any arguments on the substance of the proposal. Arguably as a result many referendums have fallen short of deliberative ideals with confusion and uncertainty amongst voters across many referendums.

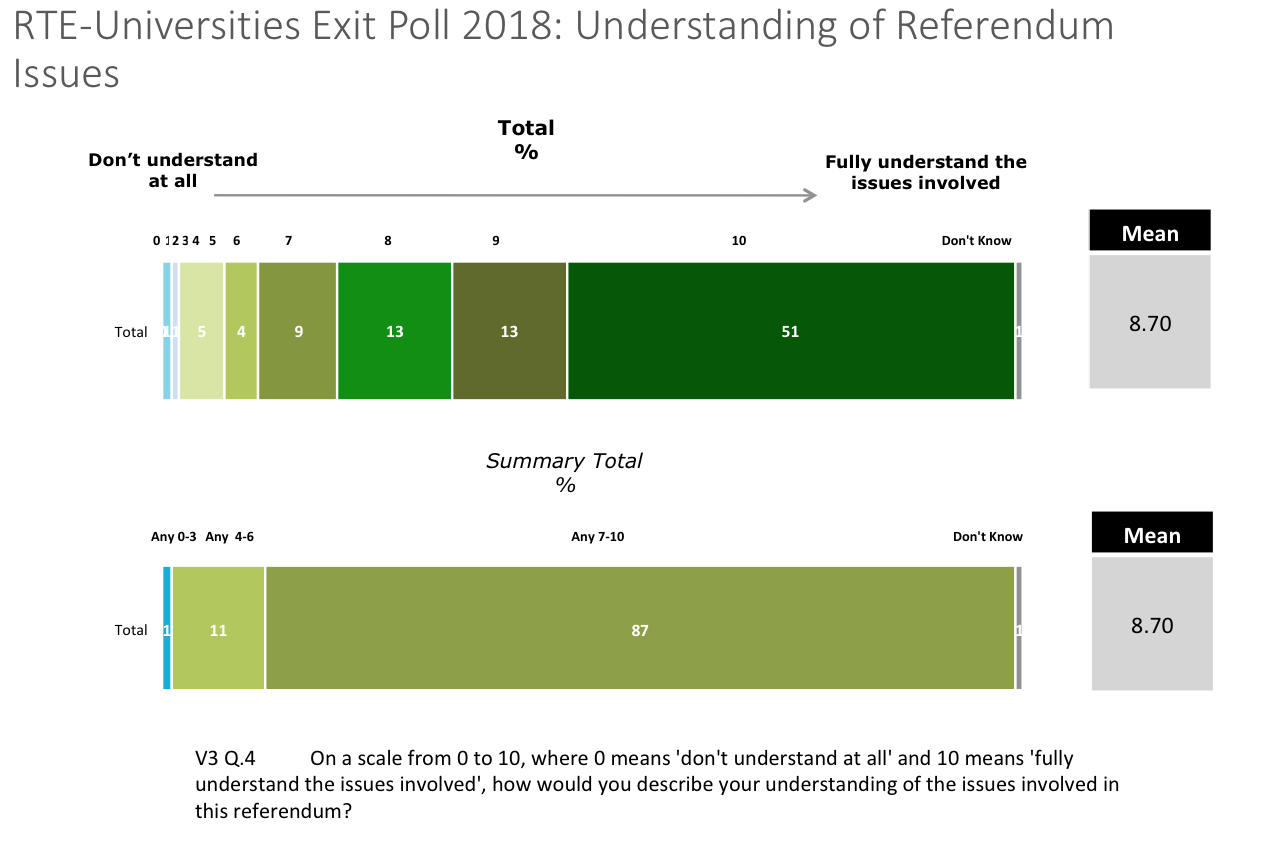

Following the deliberative assemblies and substantial civil society involvement in the marriage equality and abortion referendums, close to 90% of voters felt they fully understood the issues. This compares with just 47% (admittedly just among No voters due to the poor data collected) in the Children’s Referendum just a few years earlier. Those who are more informed are more likely to vote, and more likely to vote Yes, thus significantly contributing to the referendum outcome.

There may also be a turnout impact. Turnout in the marriage referendum was 62.1%, a 20-year record in the history of Irish referendums. Abortion was even higher at 66.4% with reportedly high turnouts of younger voters. However, given we have to rely on an exit poll rather than on a referendum study we cannot be sure of the exact demographic make up of the vote.

The tentative answer then for referendums (in Ireland at least) is that information provision matters; experts matter; and deliberation matters as well. But there are fewer answers for abortion provision in Northern Ireland, where ‘its laws breach human rights, and its people back change, but politicians remain resistant to change’. The DUP is vehemently pro-life and Theresa May, no doubt mindful that the DUP is crucial to propping up her government, has already insisted that the question is a matter for Northern Ireland’s own leaders. In addition, there is no constitutional barrier to abortion. Nonetheless, an advisory referendum preceded by a deliberative assembly may well lay the foundations for a change in the law.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It was first published on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

About the author

Jane Suiter is Associate Professor at the School of Communications at Dublin City University. She is part of the Voters, Parties and Elections research group with DCU, UCD and UCC which took part in the RTE/Universities Exit Poll.

Jane Suiter is Associate Professor at the School of Communications at Dublin City University. She is part of the Voters, Parties and Elections research group with DCU, UCD and UCC which took part in the RTE/Universities Exit Poll.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.