‘How We Vote’: British Columbia faces a complex choice about its electoral system

British Columbia’s voters face their third referendum on reforming the province’s electoral system. Christopher Stafford looks at the choices they face, and notes that the participation (or not) of undecided voters will be key to the result of this postal-vote referendum.

BC Attorney General presenting report on electoral reform proposals. Picture: Province of British Columbia, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

BC Attorney General presenting report on electoral reform proposals. Picture: Province of British Columbia, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Between 22 October and 30 November 2018, the Canadian province of British Columbia will be holding a referendum on whether or not to change the system used to elect provincial representatives. Currently, such representatives are elected using a ‘first-past-the-post’ system and B.C. voters are being asked if they wish for this to continue or if they would like to change to a system based on proportional representation. This is British Columbia’s third referendum on electoral reform, with prior votes in 2005 and 2009 not resulting in any change to the electoral system. This latest referendum is the result of a coalition between the left-leaning NDP and Green parties, both of whom promised a referendum during their 2017 provincial election campaigns. This election initially resulted in a minority Liberal government, a much more right-leaning party than their national namesake, but was soon replaced by the coalition who sought to make good on their promise.

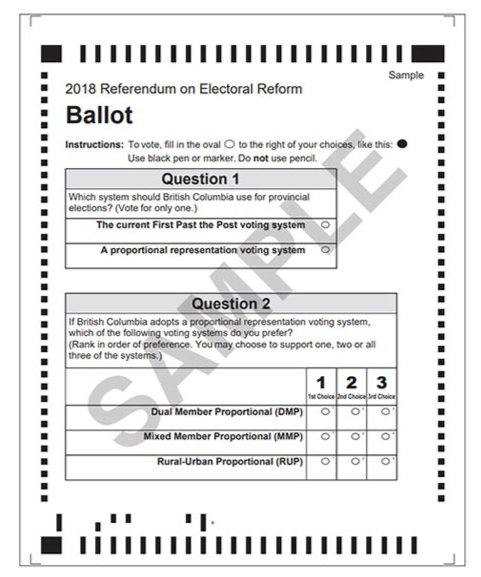

The ballot, conducted via post, will present voters with two questions. The first will ask voters if they wish to stick with the current system or change to one based on proportional representation. The second question then asks voters which of three PR options they would prefer to see implemented if the majority vote for change, asking them to rank three different systems. These three systems are ‘dual member proportional’ (DMP), ‘mixed-member proportional’ (MMP) and a ‘rural-urban’ proportional system.

The Ballot Paper. Source: https://pressprogress.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/referendum-ballot.jpg

The dual-member proportional system is currently a theoretical system, and while it has been an option on several reform referendums in Canada it has yet to be implemented anywhere. Under this system, each electoral district would have two representatives, and in most cases political parties will field a team of two candidates in a district, a primary and a secondary. The first seat in a district would be allocated to the primary candidates of the party that wins the most votes there. The second seats would then be allocated based on the overall vote, with the idea being that parties would receive seats in districts where they performed strongly. Ideally, this would therefore result in the proportion of seats for each party roughly reflecting their proportion of the overall vote.

The second proposed alternative, the mixed-member proportional system, is the same system used in legislatures in countries such as Germany and New Zealand, as well as Scotland, Wales and the London Assembly in the UK (where it is generally known as AMS, additional member system). Voters would have two votes, the first being used to choose a local representative in a single-seat constituency, and the second to support a political party. Seats in the legislature would then initially be filled based on the candidates who win the most votes in each district. Once all these seats have been determined, the votes cast for each political party would be taken into account, with the remainder of the seats in the legislature allocated proportionally to reflect the share of the vote for each party as closely as possible.

The final option, the rural-urban proportional system, is a hybrid system, where in rural areas representatives would be chosen using the aforementioned mixed-member proportional system. In urban areas the single transferable vote (STV) method would be used, with voters ranking the candidates in order of preference and there being a quota of votes needed for a candidate to be elected in multi-member constituencies. If no candidate reaches this quota in the first round of counting, the candidate with the lowest share of the vote is eliminated, and the alternative preferences of those who voted for them are taken into account, with this process continuing until enough candidates reach the quota and all of the seats are assigned.

Although the official campaign period started on 1 July 2018, it was somewhat of a phoney war, with no significant campaigning occurring until the referendum date loomed closer in late September and early October. The governing NDP and Green parties support a move to PR, while the recently ousted Liberal Party have opposed it, but the key campaigners have been the official ‘no’ and ‘yes’ campaigns, with social media being used to good effect. The proponents of moving to a PR-based system claim that the systems on offer would be much fairer because they would result in parties getting a similar share of seats to votes and as such a more consensual style of governing. Those opposed to PR claim that it is too confusing and provides unstable government, threatening that it is the ‘prefect platform’ for extremism.

A major problem in this referendum is that the finer details for the three proposed alternatives would not be determined until after the public have made their choice, meaning there are a lot of unknowns regarding exactly what kind of system voters would be choosing. Those campaigning against PR have managed to take advantage of this, using the lack of clarity to make bold and mostly unsubstantiated claims about extremism, backroom deals and lack of local accountability. It is, for example, somewhat disingenuous to claim districts would be too large to offer effective local representation when at this point in time no one actually knows how the province will be divided up.

Of course, similar arguments can be applied to claims made by the pro-PR camp, with many of the supposed benefits that would accrue from a move to PR being based on assumptions of ideal implementation after the referendum. Those in favour of a change have relied on studies of other countries that suggest PR is generally believed to increase voter turnout and also aid the representation of women and minorities, the latter of which is important in Canada and specifically in B.C. where First Nations and other minorities are often seen as underrepresented. Proponents have used the standard arguments, such as those presented by Lijphart, that consensus-based politics fostered by PR systems results in better democracies, with more cross-party cooperation benefitting a broader range of peoples.

While for some, consensual government is a good thing, others believe that it slows down democratic processes and that the deals struck between parties in coalition agreements are beyond the control of voters. Given how long a coalition agreement can take to negotiate, such claims are not without merit. However, claims that representatives will no longer be chosen by the people, but by algorithms and shady backroom deals are less convincing given what is actually known about the proposed new systems, all of which propose that all assembly members will be chosen by the voters from open lists (where voters can express a preference for individual candidates as well as for their chosen party). Even the ‘assigned’ MPs, who would be the minority in the legislature, are chosen based on personal candidate votes. Of course, these open lists are predetermined by the political parties, but candidates in FPTP systems are similarly determined by political parties, with voters having little say on who they are or where they are from.

All of this uncertainty is of course likely to affect undecided voters the most, who according to some polls account for a third of voters, the other two-thirds being split almost evenly between support and opposition to PR. Those convinced of the merits of PR are willing to take the risk on a new, but not yet fully developed system, while those opposed to it are also unlikely to change their mind. Assuming such messages reach the undecided, the result will likely depend on which side of the campaign is more convincing – whether it is scare tactics or messages of hope that resonate most with voters. Perhaps more crucially though, voters need to be motivated to fill in and return their ballot, rather than it just sitting forgotten under a bunch of flyers and other unwanted mail.

Turnout at the 2005 and 2009 referendums was 61.48% and 55.12% respectively, and with the former referendum the majority of voters actually endorsed the change on offer, but support fell just a couple of percentage points short of the threshold needed to enact the change. However, both of these referendums only offered a simple choice between the status quo and an STV-based system, whereas this latest referendum offers voters much more of a choice. Whether this abundance of options encourages voters to participate in a decision about their democracy or proves abstract enough to put them off doing so altogether, remains to be seen.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Christopher Stafford is a PhD student at the University of Nottingham, focusing on democracy and representation. His current research investigates how MPs have reacted to the result of the EU membership referendum and how this relates to the opinions of their constituents.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.