Losing the ‘Europeanisation’ meta-narrative for modernising British democracy

Contrary to claims of Britain’s enduring political and constitutional distinctiveness, in the period from 1997 to 2016 the UK in fact modernised its polity by following several strong ‘Europeanisation’ trends. British democracy came to increasingly resemble other European liberal democracies in some fundamental ways. Yet now this meta-narrative may be lost following Brexit. Patrick Dunleavy explores some implications of the UK’s possible lapse back into rudderless idiosyncrasy.

Picture: By Ilovetheeu, via a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence, from Wikimedia Commons

One of the least appreciated aspects of the 2016 Brexit referendum vote may be the disappearance of a previously influential narrative of what has been happening to British democracy, and of a template for where it will go in the years ahead. The advent of the Labour government under Tony Blair in 1997 sparked a whole series of major constitutional changes. Traditionalist critics (like Anthony King in his book The British Constitution) complained that there was no coherent plan behind Labour’s changes, that ministers had tinkered with a huge range of institutions without being clear what they were trying to achieve.

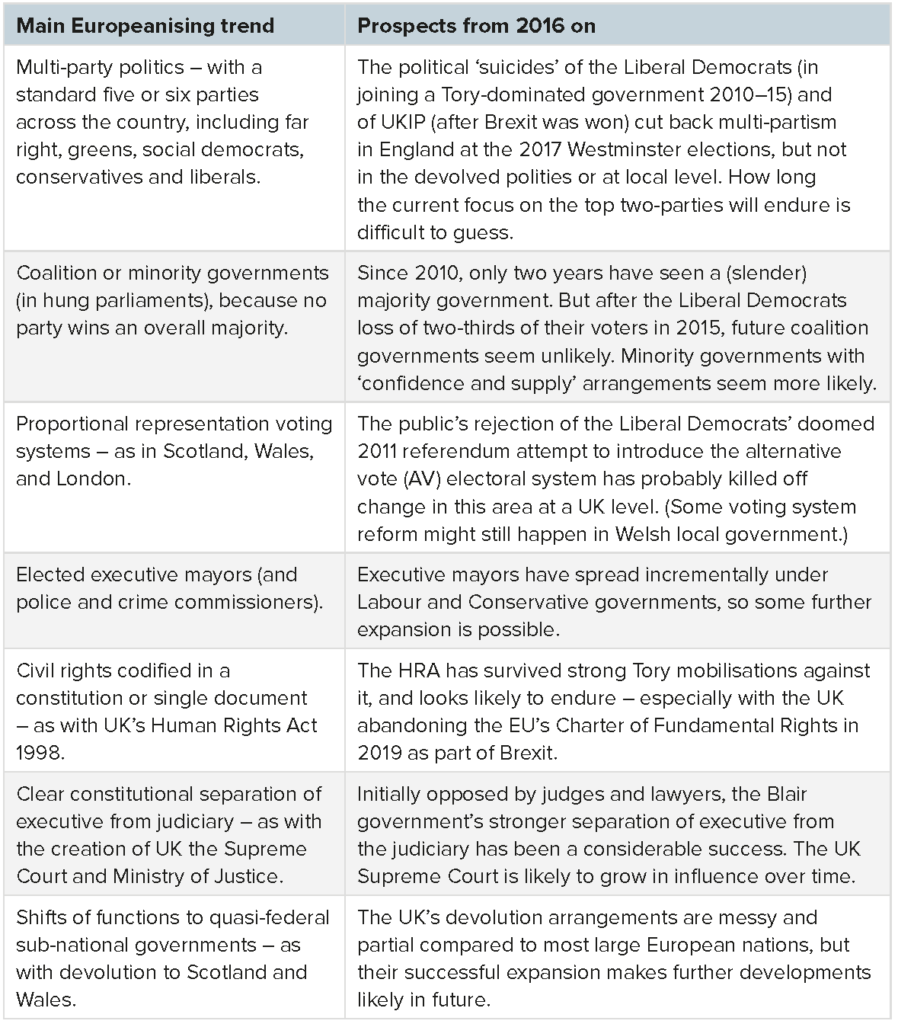

There is an alternative interpretation, however, namely that from 1997 to 2016 the UK was strongly Europeanising, falling into line with patterns of political development that were (and still are) common to almost all countries across western Europe. The cumulative effect of these changes was to ‘normalise’ and ‘modernise’ UK democracy, moving away from past patterns of British exceptionalism and uniqueness compared with neighbouring states. Table 1 shows some of the most important ‘Europeanising’ trends over these two decades, and asks whether they are likely to continue post-Brexit.

Figure 1: Six main ‘Europeanisation’ trends within the UK 1997–2016, and their likely future prospects

Source: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit (edited by Patrick Dunleavy, Alice Park and Ros Taylor), Chapter 8.2, Figure 1.

Can the ‘British political tradition’ provide an alternative modernisation template to the Europeanisation/normalisation pathway after exit from the EU in March 2019? Some critics argue that Brexit, plus the SNP push for Scottish independence, taken together with a prevailing mood of ‘anti-politics’ distrustful of established elites, mean that the Westminster model has never been more contested. Its ‘focus on strong rather than responsive government distances Westminster from citizens’, according to Marsh and colleagues.

Nonetheless, given the history of the UK’s political evolution, it is not out of the question that Brexit leads to a re-emphasis on British exceptionalism, a renewed emphasis on traditional or historical themes in a ‘back to the future’ mode. Echoes of such a position are strongly present amongst Conservative Brexiteers, and powerfully underlie Boris Johnson’s (much misquoted) complaint against May’s Chequers deal, that: ‘We have wrapped a suicide vest around the British constitution – and handed the detonator to [the EU]’. What might be the elements of a resurgence of UK exceptionalism? Some possible pieces are already on the board, including: the 2011 referendum rejection of the alternative vote as a ‘reform’ of plurality rule; the 2017–18 revival of two-party dominance (produced by the successive collapses in support for the Liberal Democrats and UKIP) in England; and the re-creation of some mass membership parties.

Combined with the cultural backlash that Brexit represents, especially if a charismatic leader like Johnson becomes Prime Minister at any stage, it is conceivable that these and other developments may bring the Europeanisation trends above to a juddering halt, so that the UK’s previous ‘exceptionalism’ from European democratic patterns continues indefinitely.

The final scenario is that Europeanisation trends peter out over time, but that the challenges posed by Brexit and some radically new problems (like adapting to digital-era politics and the growth of social media) mean that the UK’s political system stagnates, or deadlocks, or moves randomly from one uncertain situation to another, with no coherent map or narrative of future development. ‘Taking back control’ of economic regulation, trade, immigration and much more is the biggest change in UK governance for half a century. It has already produced enduring crises for the party system, Parliament and the core executive, with uniquely contested governance over critical issues, and a rapidly changing political landscape. There may well be more of the same ahead as the UK lapses into rudderless idiosyncrasy, with no meta-narrative of political or constitutional progress at all.

This article was first published on LSE’s European Politics and Policy blog. It draws on material from our new open access book edited by Patrick Dunleavy, Alice Park and Ros Taylor, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit (published by LSE Press on 1 November 2018).

About the author

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the London School of Economics, and Centenary Professor at the University of Canberra. He is the lead editor of The UK’S Changing Democracy (LSE Press, 2018), published free and open access.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the London School of Economics, and Centenary Professor at the University of Canberra. He is the lead editor of The UK’S Changing Democracy (LSE Press, 2018), published free and open access.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] so as the Brexit process unfolds. There is both huge opportunity and risk in these changes. The ‘Europeanisation’ of political life we have experienced over the last two decades – with the introduction of […]