They’re making a list: the inexorable rise of the special political adviser

The government has released its annual data on the number of special advisers it employs. Andrew Defty assesses the figures and discusses how the numbers have grown over successive governments.

Theresa May with Number 10 staff. Picture: Number 10, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Every year since 2010, usually at around this time of year, the government publishes a list of special advisers and their salaries. The latest data release, which took place this week, on 19 December, revealed another rise in the number of these highly paid political appointees.

Special advisers are temporary civil servants employed by government to provide political advice to ministers. Their roles vary considerably from providing media advice to policy expertise but, unlike permanent civil servants, special advisers are not required to be politically impartial. As political appointees, special advisers generally leave office when a government changes and new governments bring their own advisers, many of whom will have been employed by the party when in opposition.

The use of political advisers by governments is not a new phenomenon, but the number and role of special advisers has expanded considerably in recent years. The most significant expansion followed the election of the Labour government in 1997. Through 18 years of opposition and particularly in the run-up to the 1997 election, Labour had developed a large cadre of advisers and, in particular, media strategists whose services they wished to retain. Following the 1997 election, many of these individuals found themselves working alongside ministers and civil servants and in certain circumstances were even given the authority to issue instructions to civil servants.

There has been some movement towards regularising the work of special advisers in recent years. On appointment special advisers become employees of the civil service, rather than the party. As such they are covered by the Civil Service code and in 2001 the Cabinet Office produced a separate code of conduct for special advisers. This describes special advisers as ‘a critical part of the team supporting ministers’ but also suggests that their appointment may help to protect the civil service from accusations of politicisation:

They add a political dimension to the advice and assistance available to Ministers while reinforcing the political impartiality of the permanent Civil Service by distinguishing the source of political advice and support. Special advisers should be fully integrated into the functioning of government. They are part of the team working closely alongside civil servants to deliver Ministers’ priorities. They can help Ministers on matters where the work of government and the work of the government party overlap and where it would be inappropriate for permanent civil servants to become involved. They are appointed to serve the Prime Minister and the Government as a whole, not just their appointing Minister.

Government transparency and special advisers

In opposition the Conservative Party was critical of Labour’s use of special advisers. The Conservative Party manifesto for the 2010 general election promised to reduce the cost of government and to make government more accountable and transparent. This included an unequivocal commitment to ‘put a limit on the number of special advisers and protect the impartiality of the civil service.’ This commitment to reducing special adviser numbers was repeated in the Coalition Programme for Government.

The special adviser data release is an admirable example of openness in government. Previous governments had also provided data on the employment of special advisers, but these had generally come in response to parliamentary questions. The first special adviser data release in June 2010 provided a model which has been followed every year since. It included the names of all special advisers then in post, their pay band and, in the case of the most well-paid special advisers, their actual salary.

The timing of the data release has not, however, been ideal in terms of encouraging scrutiny. The date of the release has varied but there has been a tendency to issue the data on a day when Parliament is going into recess or, in some cases, when Parliament is not sitting. Every year since 2014, including the current year, the data has been released on or just before Parliament rose for Christmas. Issuing the data just before a recess means that the release is often buried in a flurry of other announcements, it may also reduce the opportunity for uncomfortable parliamentary questions about the Government’s use of special advisers.

The inexorable rise in the number of special advisers

The possibility of uncomfortable parliamentary questions is perhaps enhanced by the seemingly inexorable rise in the numbers of special advisers and also the, not inconsiderable, salaries attached to some of these posts.

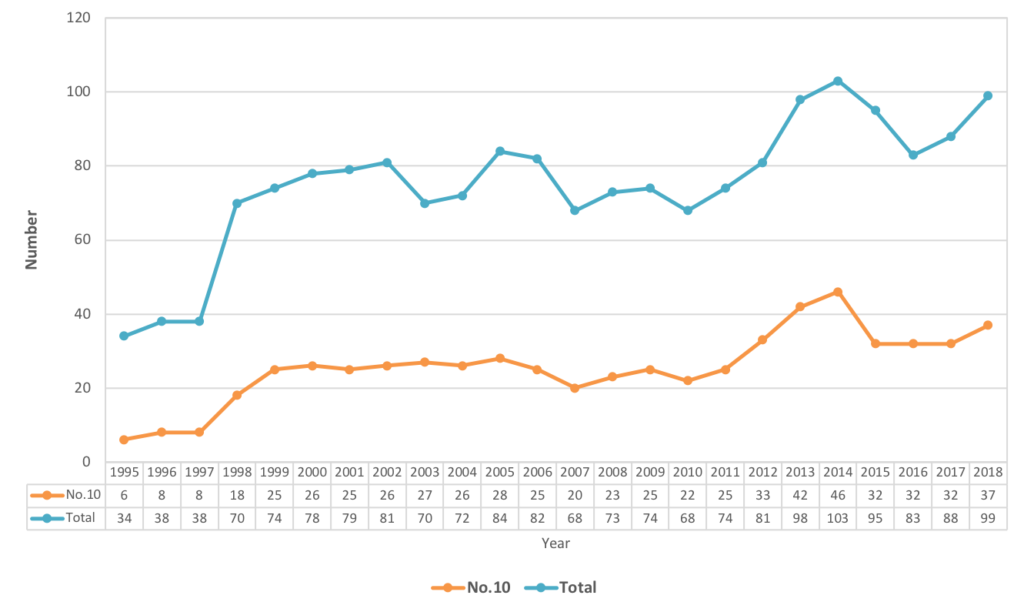

The total number of special advisers certainly increased considerably under Labour, almost doubling from 38 in the final year of the Major government to 70 at the end of Labour’s first year in power. The total number of special advisers under Labour peaked at 84 in 2005. Following the election of the coalition government in 2010 there was a slight fall in the number, but this soon began to rise. Despite promising to reduce numbers, by 2013 the number of special advisers employed by the coalition government had surpassed Labour’s peak and kept on rising.

Although the numbers fell again following the 2015 general election they have once again begun to rise. This year’s release reveals that 99 individuals are currently employed as special advisers, although three of these work part-time. There are currently more special advisers than at any point under Labour and almost as many as during the highest point of the coalition government.

Figure 1: Special adviser numbers since 1995

Although the number of special advisers employed by the coalition government can, in part, be explained by the need to provide advisers for both parties in the coalition, this does not account for all of the additional numbers. By the final year of the coalition there were 20 supporting the Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, and the other fourteen Liberal Democrat ministers. However, the total number had by this point risen to 103, with 83 of those supporting Conservative ministers.

Other more significant and long-term factors in the rise in special adviser numbers are the increase in size of the government and also the concentration of advisers in Downing Street. There is no statutory limit on the number of special advisers, but the Ministerial Code allows for the appointment of two special advisers to each Cabinet minister and one to any other minister attending Cabinet. The size of the Cabinet has grown under Theresa May, there are currently 23 full Cabinet ministers and a further six ministers attending. Moreover, some ministers are clearly exceeding their allocation. There are at present five Secretaries of State with three special advisers while the Home Secretary has four. Interestingly, in the last year, the number in the whips’ office has doubled from two to four. Moreover, there are no limitations on the number of advisers allocated to the Prime Minister. Since the late 1990s around a third of all special advisers have been located in Number 10, although this has also increased since 2010. Half of this year’s increase in special adviser numbers can be attributed to advisers appointed by Number 10.

Special advisers in context

Perhaps wary of the potential for criticism the government also now provides some contextual data with the annual special adviser data release. It notes that while there are 99 special advisers working in government, there are a total of 430,075 civil servants working across the country. It also notes that the total cost of special advisers at £8.1m per calendar year, is only 0.05% of the total civil service budget. This cost is also compared to the £9.8m of state funding which is provided through Short Money to support opposition parties with seats in the House of Commons, and the £1m of Cranbourne Money which supports opposition parties in the House of Lords.

This is certainly interesting contextual data although it does allow for a number of other conclusions. The number of special advisers is indeed tiny when compared to the massed ranks of civil servants, but the reason why parties in government have not historically relied upon special advisers, is precisely because they have been able to draw on the considerable resources of the civil service. Similarly, in relation to the funding provided to opposition parties, this is designed to allow opposition parties to be able to carry out their parliamentary business, in order to provide effective scrutiny of the government. It is paid to opposition parties and not the government, because opposition parties do not have the resources available to the government. While the data provided in the current release indicates that funding for opposition parties is slightly more than the total budget for special advisers, opposition parties receive no other state support, while governments are able to draw on the support both of special advisers and the civil service.

Moreover, it is very difficult to avoid the fact that special advisers are very highly paid individuals, operating at the higher levels of the civil service in Whitehall. While there are considerable drawbacks to being a special adviser, not least job-insecurity, they are considerably better paid than most civil servants and, in many cases, than most Members of Parliament. On the basis of the figures provided in the current release, the average salary for a special adviser is more than twice the average salary for the other 430,075 civil servants, while 22 special advisers currently earn more than the current basic salary for an MP of £77,379.

The growth in numbers, cost and influence of special advisers has been a source of considerable concern for some time. Several inquiries have recommended a cap on special adviser numbers and opposition parties have often been critical of their use. Yet in government no party has felt able to arrest the trend begun by Labour in 1997. At a time when the impartiality of the permanent civil service is frequently being brought into question, some attention might justifiably be focused on the impact of this small, yet ever-expanding, group of highly paid political appointees.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Andrew Defty is a Reader in Politics in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln. He runs the Watching the Watchers blog at Lincoln University and is co-author, with Hugh Bochel and Jane Kirkpatrick, of Watching the Watchers: Parliament and the Intelligence Services, published by Palgrave.

Andrew Defty is a Reader in Politics in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln. He runs the Watching the Watchers blog at Lincoln University and is co-author, with Hugh Bochel and Jane Kirkpatrick, of Watching the Watchers: Parliament and the Intelligence Services, published by Palgrave.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.