Has the gender gap in voter turnout really disappeared?

While the gender gap in electoral representation is widely acknowledged, it is often assumed that there is no equivalent underrepresentation of women in voter turnout. However, Filip Kostelka, André Blais and Elisabeth Gidengil find that, while women vote in equal numbers in first-order national elections, less high-profile local and supranational elections still see a disparity in turnout between men and women, which has implications for equal participation.

Women campaigning for US mid-term elections. Photo by Mirah Curzer on Unsplash

Women campaigning for US mid-term elections. Photo by Mirah Curzer on Unsplash

While women represent about half of the global population, they hold fewer than a quarter of legislative seats worldwide. They contact their elected representatives, work for political parties and protest less frequently than men. Even in the most advanced democracies, women’s voices are underrepresented in politics.

Many believe that gender equality has been achieved at least in the most fundamental and common form of political participation: voter turnout. Studies in political science commonly refer to the ‘well-known [gender] equivalence in voter turnout’, observing that women vote as much or even more than men. Our new article, published in West European Politics, significantly qualifies this optimistic assessment. It demonstrates that full gender equality has been achieved only in the most important elections, which are typically the national elections. In elections that voters consider to be of lesser importance, such as elections to regional assemblies (i.e., subnational elections) or the European Parliament (supranational elections), women still participate at significantly lower rates than men.

Two findings in the literature motivate our study. First, previous research has shown that women are less psychologically engaged in politics. In surveys, they typically report lower levels of political interest and give fewer correct answers when asked political knowledge questions. Second, as some pioneering theories in political science suggest, psychological engagement in politics is likely to matter more in what have been termed second-order (i.e., less important) elections. In such elections, political competition receives weaker media coverage and parties strategically invest fewer resources in campaigning. Additionally, the competencies of the elected bodies are often unclear to ordinary citizens and, particularly in the case of the European Parliament, the link between election outcomes and policy seems tenuous.

Second-order elections thus provide citizens with an environment that is less conducive to electoral participation: the stakes are less clear, information is scarcer and social pressure to participate is weaker. When compared to first-order elections, voting in second-order elections is costlier and less rewarding. Those who care less about politics, whom earlier research called ‘peripheral voters’, would be expected to abstain more often. Based on what we know, women should be over-represented among peripheral voters and, therefore, should vote at lower rates then men in second-order elections.

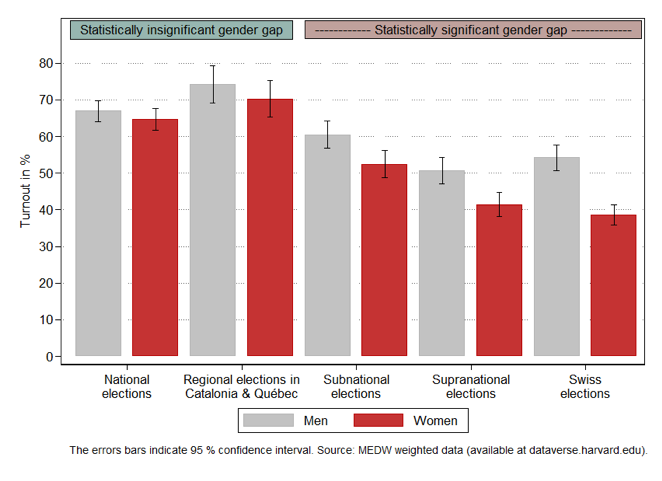

We test this theory using two datasets (Making Electoral Democracy Work and the European Election Study) with survey data that cover voting in national, subnational and supranational elections in a large variety of European democracies and Canada. The results support our hypothesis. In most countries, men do not vote at significantly higher rates than women in national elections (i.e. the difference between the sexes is statistically insignificant). By contrast, there is a statistically significant gender gap, with women being less likely to vote, in both subnational and supranational elections. This gender gap is also observed in Swiss national elections, whose importance is reduced by the existence of a power-sharing deal and frequent use of referenda. Conversely, no gender gap is observed in Catalonia and Quebec’s subnational elections, where the importance is boosted by the heated question of regional autonomy and the presence of strong regional parties. This variation is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Gender gap by election type

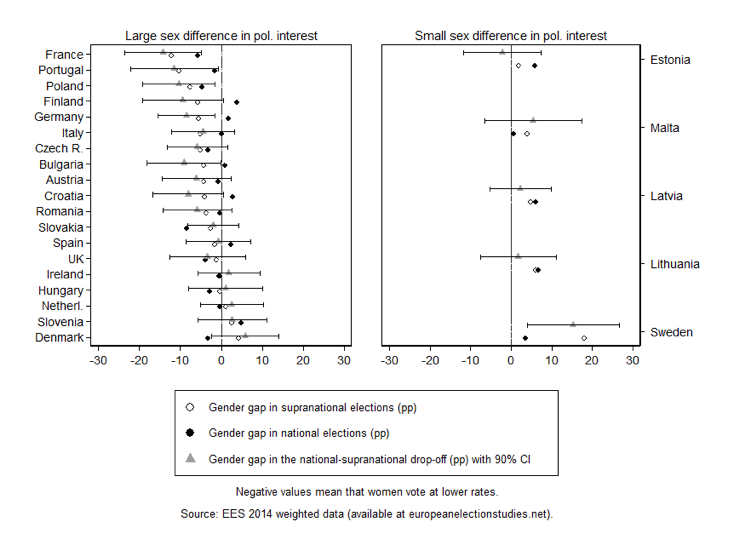

In conformity with our theory, the magnitude of the gender gap in voter turnout varies proportionally to the gender gap in psychological engagement in politics. In those countries where the difference in political interest between men and women is small, women vote as much or even more than men in supranational elections. By contrast, in those countries in which women are significantly less interested in politics than are men, there is a gender gap in supranational elections. As a consequence, women are over-represented among those citizens who vote in national elections but do not vote in supranational elections.

Figure 2: Gender gap by country (national and supranational elections)

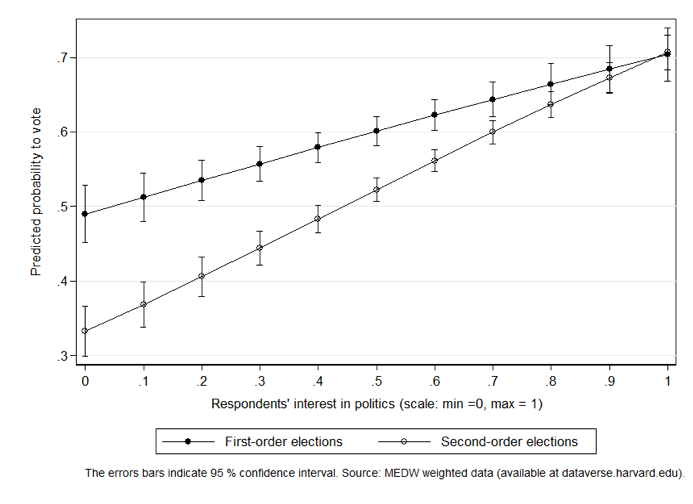

The core causal mechanism at work is graphically illustrated in Figure 3. The figure shows the relationship between political interest and electoral participation in first-order and second-order elections. While the most interested participate at the same rate in first-order and second-order elections (about 70% in our data), the least interested are 15 percentage points less likely to vote in second-order elections when compared to first-order elections (i.e. the voting rates are 48% and 33% respectively). This has implications not only for women but also for other groups with lower levels of political interest, such as young people and less educated citizens. The voices of these groups are likely to be even more underrepresented in subnational and supranational elections than in national elections.

Figure 3: Political interest and voting in first-order and second-order elections

With regard to the main research question, these findings demonstrate that the gender gap in voter turnout has not yet completely disappeared. In many countries, women still participate at lower rates than men in subnational or supranational elections. This is substantively important. Although those elections are usually called second-order and voters care less about them, the elected bodies do decide on important issues and, lately, their competencies have tended to grow. Normatively, the observed gender gap in voter turnout clashes with the ideal of democratic equality. Our research suggests that that the best way to address this issue is to reduce sex differences in psychological engagement in politics, which, as many studies suggest, probably originate in the processes of socialisation. Therefore, our societies may need to change the way people learn about politics and build their political identities.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. For more details of their research, see Filip Kostelka, André Blais & Elisabeth Gidengil (2018), ‘Has the gender gap in voter turnout really disappeared?’, published in West European Politics.

About the authors

Filip Kostelka is Lecturer in Government at the University of Essex.

Filip Kostelka is Lecturer in Government at the University of Essex.

André Blais is Professor in the Department of Political Science and holds a Research Chair in Electoral Studies at the University of Montreal.

André Blais is Professor in the Department of Political Science and holds a Research Chair in Electoral Studies at the University of Montreal.

Elisabeth Gidengil is Hiram Mills Professor in the Department of Political Science at McGill University and a member of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship.

Elisabeth Gidengil is Hiram Mills Professor in the Department of Political Science at McGill University and a member of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.