Are there any benefits to divided parliamentary parties?

Intra-party dissent is generally considered a bad thing – for parties seeking power and for voters wishing to make sense of political conflicts. However, using a survey experiment to test people’s responses to different forms of intra-party policy disputes, Eric Merkley finds that there are circumstances in which voters find moderate divisions useful as cues for evaluating policy choices in light of their own preferences.

Anna Soubry, Dominic Grieve, Amber Rudd, David Davis and Jacob Rees-Mogg. Pictures UK Parliament/Open Government Licence (CC BY 3.0)

As hard as it might be to imagine with the recent goings on of UK politics, but parliamentary parties are typically highly disciplined operations. Historically MPs only infrequently cross-party lines in sizeable numbers to vote against their party’s position on matters before Parliament.

This is a good thing according to most observers and scholars of parliamentary democracy. Disciplined parties provide clear choices to voters about packages of policies they can support with their vote, and can allow them to more easily hold parties accountable if they do not follow through on their commitments. For example, what exactly is a voter to make of the Conservative Party’s position on Brexit when the party is so deeply splintered between former supporters of Remain, and hard and soft Brexiters?

There is another, less obvious benefit of disciplined parties. Most citizens form opinions and preferences on politics and policy with little information. There are few incentives to become fully informed about politics, so people often rely on heuristics – cognitive short-cuts – in the political environment to make low effort decisions that are generally in line with their interests and values. One such heuristic is to adopt the positions taken by the political party they support. Disciplined parties send consistent signals to their supporters about the policies they should or should not support. Divided parties sow confusion in their supporters’ ranks.

In a paper recently published in Parliamentary Affairs, I examine possible consequences of divided parties. I ask whether or not there are consequences of intra-party dissent over policy on the public’s support for that policy. And, if there are important implications: is it all bad? Does dissent from the party line simply confuse voters, or does it provide valuable information in its own right?

I argue that under certain circumstances divided parties can provide useful information to citizens. Dissent from the party line is a costly signal, particularly in Westminster systems. Party leaders and MPs prefer to maintain their party’s brand by forming a united front, and the latter face discipline from the former if they deviate from the party line. Parties are united more often than not, so dissent signals to citizens that there is something unusual about the party’s policy stance, like that it occupies an unfamiliar ideological space for a given party. Of particular interest for me here is that centrist dissent – where dissenters agree with the opposing party’s elites – may indicate that policy is more extreme than citizens might expect if the party was united.

Method and findings

I conducted a survey experiment to test this proposition. I exposed respondents to a series of mock newspaper articles on a policy debate on an education initiative put forward in the legislature of the Canadian province of British Columbia. These articles were designed to appear to be from legitimate and popular news sources, and respondents were led to believe the debate was recently in the news. Respondents were given a set of articles where the government party was either modestly divided or united on the initiative. And, if they were divided, dissenters either opposed the policy because it was too extreme (i.e. centrist dissent) or because it didn’t go far enough (i.e. extreme dissent).

The traditional expectation is that dissent within the government party should confuse supporters of the government and reduce their support for the policy compared to what it would have been with a united party. This should occur regardless of whether or not dissent was extreme or centrist. My expectation, however, is that dissent should reduce support among supporters of the opposition party, but only when dissent is centrist – such dissent tells opposition party supporters that the policy is further from their preferences than they might otherwise expect with a united government party.

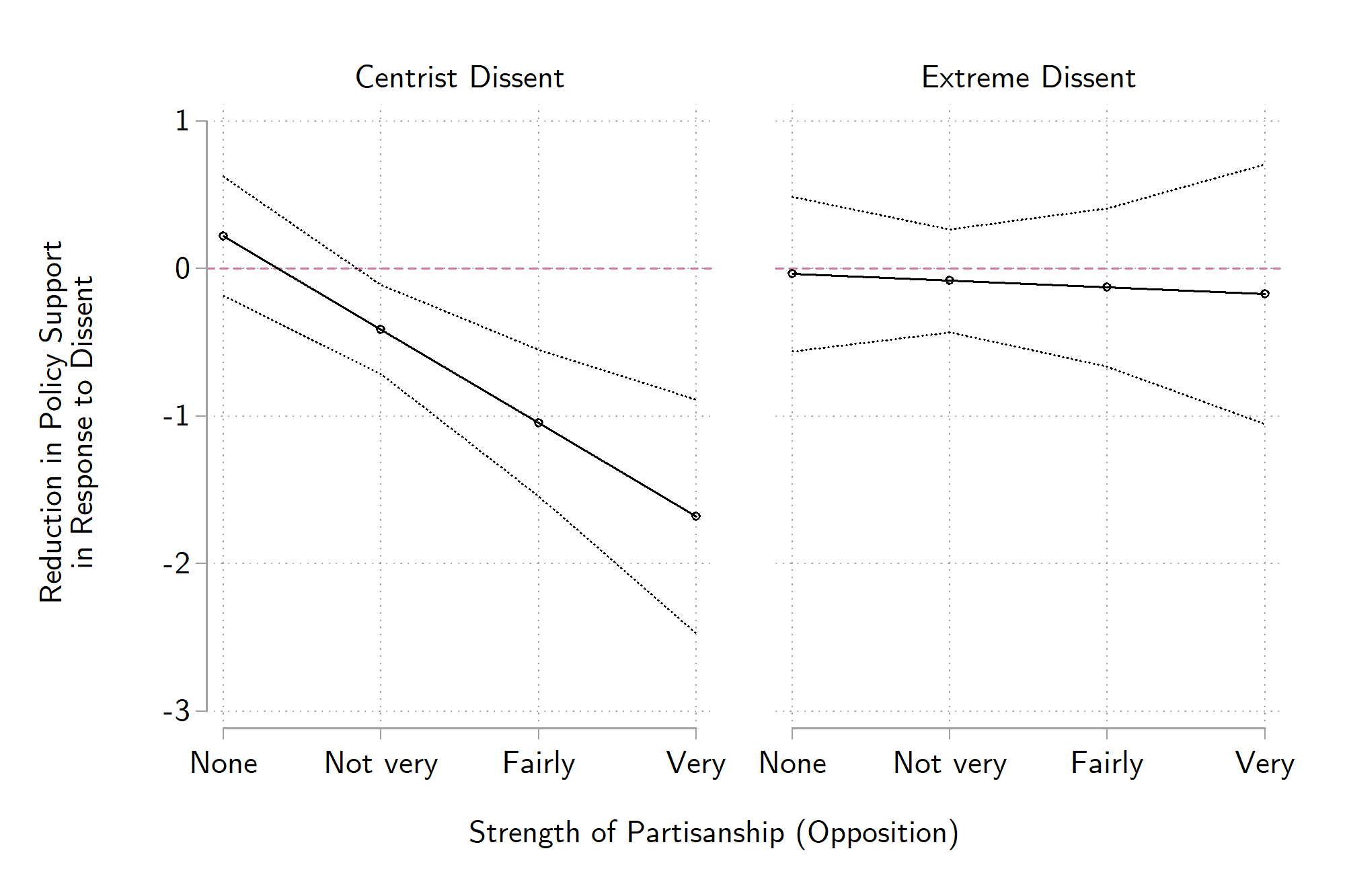

Figure 1. Estimated reduction in policy support in response to centrist (left) and extreme (right) legislator dissent across strength of opposition party partisanship.

Note: policy support measured on a 1-7 scale. 90% confidence intervals.

Note: policy support measured on a 1-7 scale. 90% confidence intervals.

The results fit more closely with my expectation. As shown in Figure 1, policy support is much lower among opposition party supporters in response to dissent on government benches, but only when it is centrist. In contrast, there are no significant effects of dissent on government supporters across both types of dissent. Respondents who support the opposition party appear to have taken a cue from centrist government dissenters that the policy might be further from their preferences than they would otherwise expect.

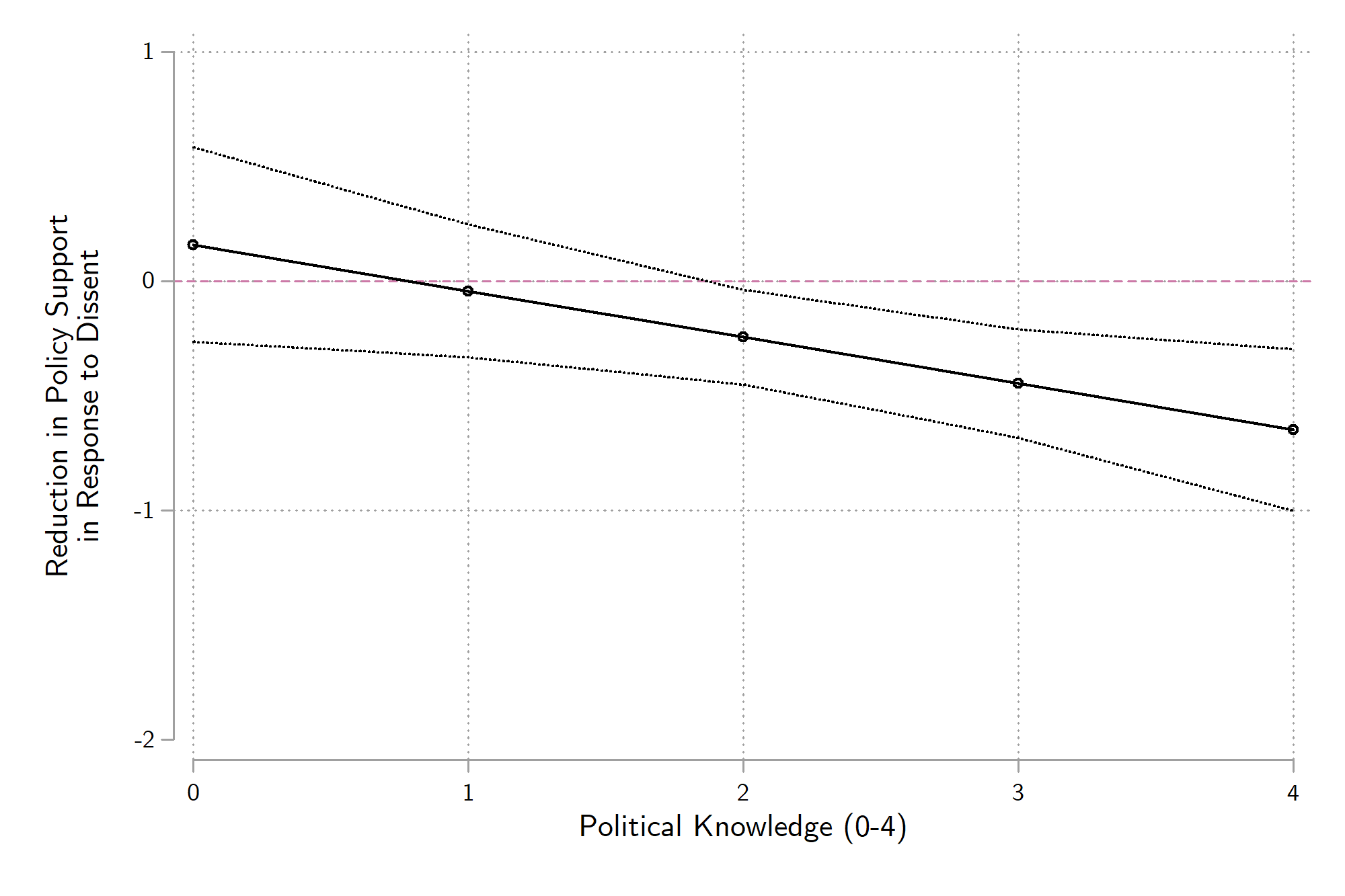

The process I have outlined for how citizens may use divided parties to inform their evaluations of policy requires them to understand why parliamentary dissent is unusual, and the implications of that dissent for the likely distance of a policy proposal from their own preferences. It is, in a word, complex, at least compared to people mechanically adopting policy evaluations in line with their partisanship. Consequently, I find that the effect of dissent on policy evaluations is stronger among those that have higher levels of political knowledge, as shown in Figure 2. If divided parties can be used as a short-cut for public opinion formation on policy issues, it is employed only by those with a strong understanding of politics.

Figure 2. Estimated reduction in policy support in response to legislator dissent across levels of political knowledge (4=highest level of knowledge).

Note: policy support measured on a 1-7 scale. 90% confidence intervals.

Note: policy support measured on a 1-7 scale. 90% confidence intervals.

Implications

So what does this mean for the practice of parliamentary politics? First, the findings suggest that government party leaders have little to fear from modest levels of dissent affecting public support for their policy agenda. Effects of dissent on support for a policy are found primarily among largely inaccessible voters – supporters of the opposition party. It is important to note, however, that this finding was made in the context of modest levels of intra-party dissent. Deeper, more widespread dissent, such as what is afflicting the governing Conservatives, may have different effects – a possible subject for future research.

Second, and more substantively, my findings suggest that we cannot be so easily dismissive of the value of divided parties. The novelty of intra-party parliamentary dissent can provide information to citizens about public policy that gets papered over by strong party discipline. Future research should not hesitate to make use of experiments to explore the implications of unity and division for public opinion.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s article, ‘Learning from Divided Parties? Legislator Dissent as a Cue for Opinion Formation’ published in Parliamentary Affairs.

About the author

Eric Merkley is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of British Columbia and a Joseph-Armand Bombardier SSHRC Scholar. He specializes in public opinion and political communication. He studies how elite behaviour shapes public opinion using experiments and time series methods.

Eric Merkley is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of British Columbia and a Joseph-Armand Bombardier SSHRC Scholar. He specializes in public opinion and political communication. He studies how elite behaviour shapes public opinion using experiments and time series methods.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Have I missed something here?

Last time I heard, Canada still has the British “first-past-the-post” electoral system. This system puts particular strains on parties to stay united over policies.

How might the results be different in countries with a representational democracy which requires a proportional voting system? This system enables a larger number of smaller parties to have a wider range of policies resulting in fewer intra-party divisions.