How not to recruit postal voters in the UK

Joshua Townsley and Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte tested the ability of parties to recruit postal voters in a field experiment carried out during the 2018 local elections in London. The result? Sending personal letters persuading voters to become postal voters is not an effective recruitment technique.

Photo by Kirsty TG on Unsplash

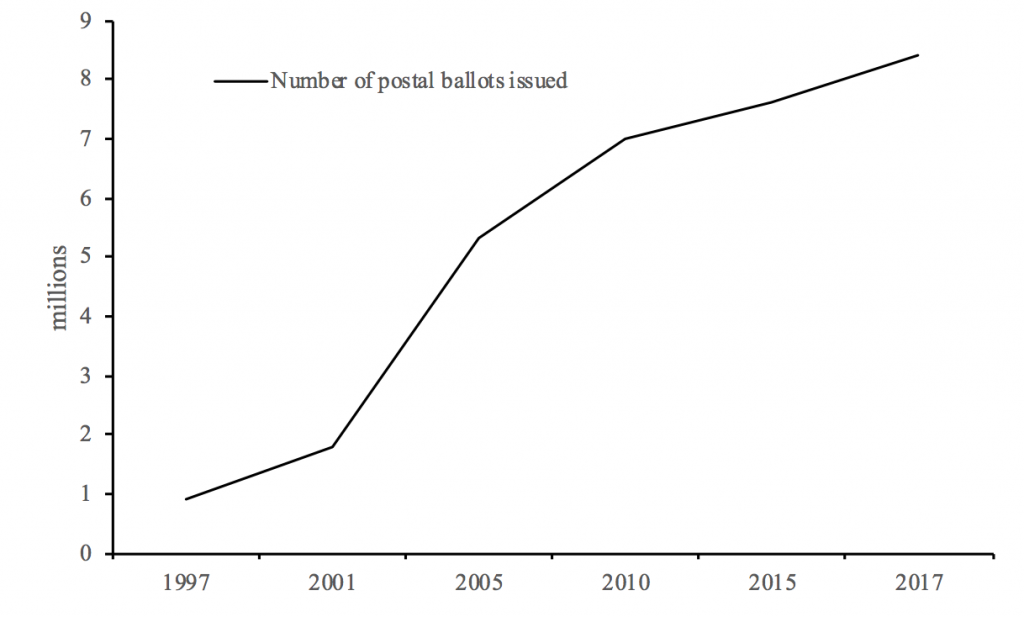

Postal voting, in line with other forms of early or ‘absentee’ voting, is a growing phenomenon internationally. Historically, allowing some citizens to cast their ballots prior to election day was a wartime procedure, introduced in order to allow soldiers who were stationed overseas to participate in elections. But in many countries, postal voting is becoming increasingly accessible to ordinary voters. In Britain, for example, the uptake of postal voting has risen at each of the last six general elections (Figure 1). The result is that votes cast by post are an increasingly important aspect of modern elections. But we know far less about how postal voting impacts on parties’ election campaigns.

Figure 1: UK postal voting trends (1997–2017)

For instance, the rise in postal voting has implications for campaign planning. As more and more voters now cast their ballots before election day, Philip Cowley and Dennis Kavanagh have noted that there are effectively multiple polling dates that campaigns have to prepare for. As well as the traditional ‘in-person’ polling day, a substantial and increasing bloc of voters now receive and cast their ballots several weeks prior to this.

To adapt to this trend, many parties now look to ways in which they can capitalise on accessible postal voting to maximise turnout of their party’s supporters. By trying to sign would-be supporters up to the more convenient postal voting, parties hope they will be more likely to actually vote – and to vote early. Banking supporters’ votes early in the campaign can only help parties, as they can focus their resources on the labour-intensive Get Out The Vote efforts needed later in the campaign. However, academic research into these practices and their efficacy is limited.

Experiment

We carried out a field experiment in cooperation with the Liberal Democrats to test whether parties are able to recruit their supports onto postal ballots. The experiment was carried out during the May 2018 local elections in a part of England where the party had enjoyed considerable electoral success in recent years.

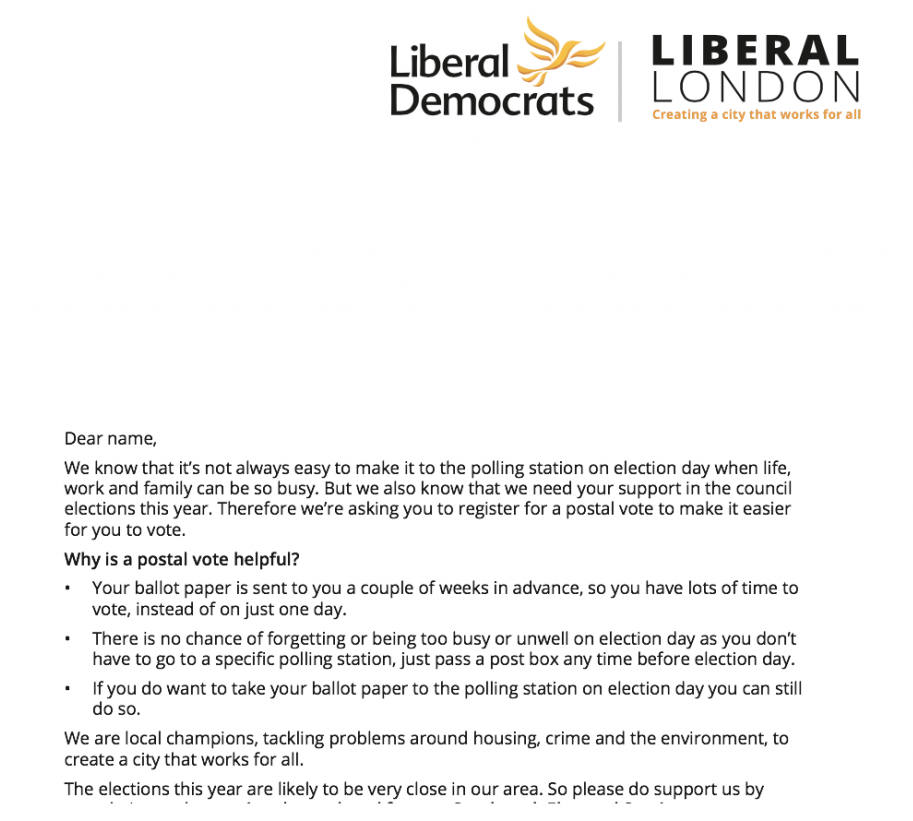

Firstly, we complied a dataset of 3,083 individuals who had been identified by the party in earlier canvassing efforts to be likely supporters of the party. We then randomly assigned 1,500 households (1,639 individuals) into the treatment group and 1,583 households (1,701 individuals) into control. Individuals in the treatment group received a personal letter (Figure 2) from the local party alongside an enclosed postal voter registration form.

Figure 2: part of the treatment letter

The letter encouraged individuals to become postal voters by emphasising the convenience of voting by post as well as promoting the local issues important to the party to encourage turnout. All of the individuals from both treatment and control groups were excluded from the party’s other local canvassing and political activities.

Results

After the election took place, we obtained the electoral register from the local council to measure our results. We were interested in two outcome variables. Firstly, we assessed if the letters had any effect on recruiting postal voters. In other words, did treatment assignment (allocation to the group that would receive the letter) increase the proportion of postal voters? Secondly, we analysed if the letters had any effect of turnout. Given that we cannot observe who actually received the treatment (we do not know if recipients opened or read the letter) we assess what is known by experimental researchers as the intent-to-treat (ITT) effect.

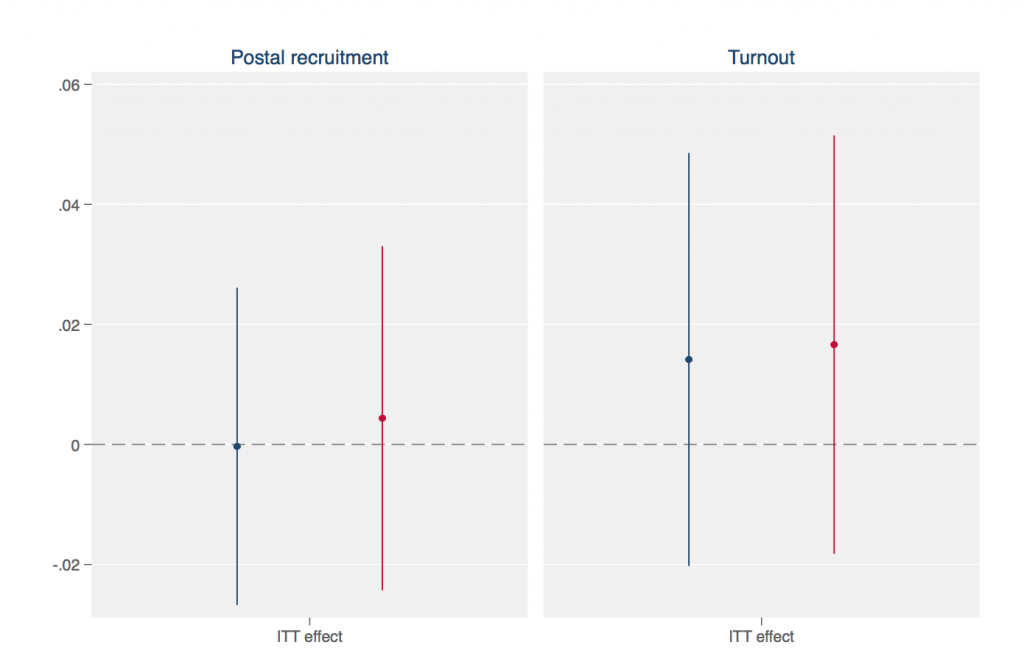

Figure 3: effects of intent-to-treat on outcome variables

Figure 3 displays the main findings. In the left-hand panel, we plot the estimated effects of treatment assignment of postal voter enrolment. In the right-hand panel, we plot the estimated effect on electoral participation. The navy lines present the modelled effect without considering confounding co-variates (gender, past participation, electoral ward) whilst the red lines represented the modelled effect of covariate-adjusted ITT effects.

In the cases of both outcome variables, treatment assignment appears to have had a negligible effect. In other words, the results of the experiment suggest that the party was unable to persuade people to alter their voting status and become postal voters.

Conclusion

The results do not necessarily mean parties should discount postal voter recruitment activities altogether. For instance, the results could be down to the local circumstances, or simply that postal voting looks less appealing to voters in densely populated London. The results do suggest, however, that parties might want to consider recruiting postal voters through face-to-face interactions, which have been shown to successfully mobilise voters in other studies.

The role that postal voting plays for party campaigns remains of interest. The ‘prize’ associated with encouraging supporters to vote at a higher rate (i.e. maximising the party’s vote share) merits further research. Not only can postal voting radically alter how local campaigns are fought, if future research establishes that postal voting increases overall participation, then this could be an avenue worth pursuing by governments and electoral authorities as a means to increase voter turnout at elections.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog. This article is based on the authors’ published work in Electoral Studies.

About the authors

Joshua Townsley is a Research Associate at the Sheffield Methods Institute and a Teaching Fellow at the University of Warwick. He researches electoral campaigns and political behaviour. Joshua also runs the LSE’s Democratic Dashboard. He tweets @JoshuaTownsley.

Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte is a PhD Candidate in Politics in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He works on comparative politics in the European Union and researches political parties, campaigns, and elections.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.