Unpaid internships in Parliament are a barrier to widening political participation

Many people who work in Parliament have previously worked unpaid for MPs, or found their current job through personal connections. Rebecca Montacute argues that to create a Parliament that is trusted and better represents the electorate, it is time to change these practices to ensure people from less privileged backgrounds have equal opportunities to pursue a career in politics.

UK Youth Parliament. Picture UK Parliament/CC BY-NC 2.0/Parliamentary Copyright

Last week, the European Parliament decided to ban unpaid internships in the offices of MEPs. From July, all interns working there will be paid directly by the Parliament itself. This follows steps taken in Washington last year to reduce the number of unpaid internships in Congress. After a successful campaign by the organisation Pay Our Interns, there are now ringfenced funds for interns in both the House and the Senate, ensuring that money is available for all interns to be paid. Countries across the world are moving to end unpaid internships in politics.

However, in Westminster unpaid work in politics is still too common. Recent Sutton Trust research found that almost one-third of all staffers working in Parliament are either currently unpaid, or have previously worked unpaid for an MP. In the Labour party 36% of staffers were currently or have previously worked unpaid, compared to 28% of those working for Conservative politicians.

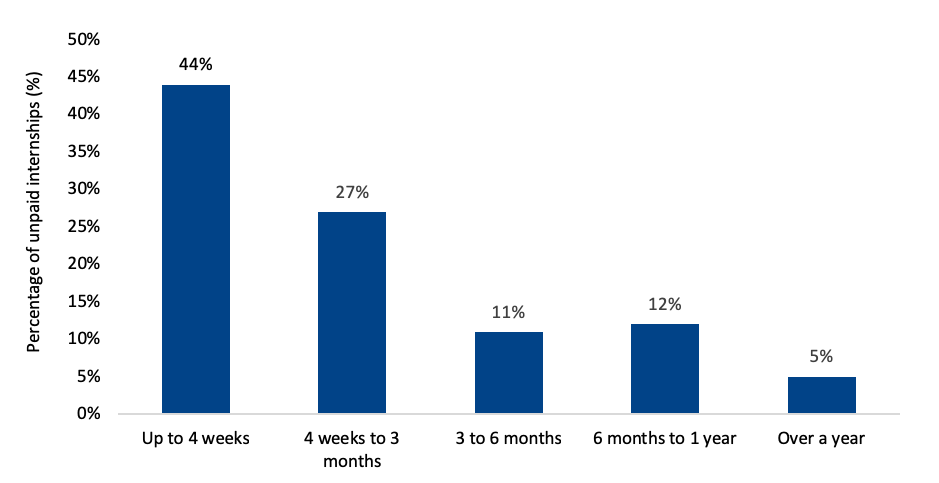

Over half (56%) of those who worked unpaid for an MP did so for over four weeks, and almost a fifth (18%) did so for longer than six months. An unpaid internship in London will set an intern back over £1,000 per month, putting these placements out of reach for young people without access to the large funds needed to work for free.

Figure 1: Length of unpaid internships in Parliament

These young people aren’t just locked out of working for MPs, they are also likely to then be shut off from other roles in politics because they can’t get that first foot in the door. Many staffers in Westminster go on to work in prominent roles in politics, policy and public affairs, in large part thanks to the knowledge and connections they gain from having worked in Westminster. Some even go on to become MPs themselves, with 25% of MPs having previously worked in politics and 8% in public affairs before running for office. The upshot is that people from more privileged backgrounds are substantially over-represented in Parliament, with 29% of MPs having been educated privately, compared to just 7% of the population.

While we know there is a problem with unpaid work in Westminster, to tackle the issue, we need much more information about how many unpaid internships are happening in Parliament and why. There are a variety of possible reasons, including a lack of funds, convenience and avoiding bureaucracy. We need to know whether MPs have sufficient resources to pay their interns, or whether it would help to ringfence funds for this purpose, as is now the case in the US. The money available for MPs to pay their staff is decided by the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA), the regulator set up in the aftermath of the parliamentary expenses scandal. However, IPSA does not currently monitor the number of unpaid internships taking place in Parliament.

That means that IPSA also does not know whether any of these unpaid Westminster internships are illegal under current minimum wage law. If such placements expect set work to be done by the intern which is of value to the intern’s employer, they are illegal, even if they have no set hours. (There are some exceptions if, for example, the internship is part of a university course.) We have previously found that illegal internships like this are being advertised in Parliament.

The Sutton Trust and others have argued that the law as it stands is not clear enough. The government have said they have no plans to change the law, but if MPs themselves do not understand the law and are taking on interns illegally, it shows that change is needed. That’s why we’re calling for a ban on unpaid internships over four weeks in length, to give clarity to both interns and their employers.

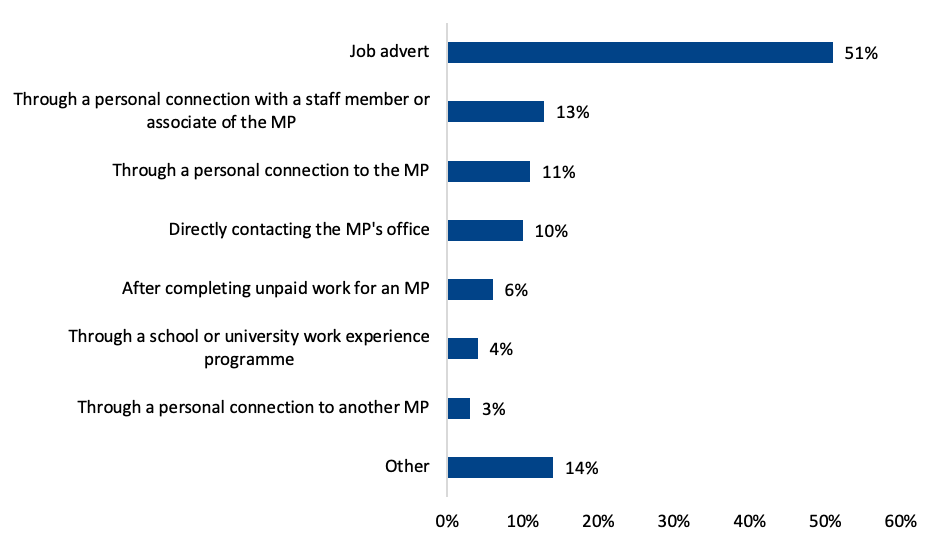

However, lack of pay isn’t the only barrier for someone hoping to work in Parliament. Our research has found that over a quarter of Westminster staffers found their current role through a personal connection, either with the MP themselves (11%) a member of staff in their office (13%), or with another MP (3%). Looking at breakdowns by political party, 29% of staffers working for Conservative politicians got their role through a personal connection, compared to 20% of those from the Labour Party. Many internships, in Parliament and elsewhere, are never publicly advertised. Not openly advertising positions locks out young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, who often will not have the networks needed to secure these positions.

Figure 2: How Westminster staffers found their current role

Parliament should be open to everyone, regardless of their background, so that it is more representative of the population as a whole. This issue is particularly stark in the current political climate, in which parliamentary democracy is being tested to its limits. Now more than ever, public faith in politicians is vital. Banning unpaid internships and requiring that all positions in Parliament are openly advertised are important steps towards opening up our democracy, to make it truly accessible to all.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit. An earlier version of this blog was published by the Sutton Trust.

About the author

Dr Rebecca Montacute is Research Fellow at the Sutton Trust and co-author of ‘Pay As You Go?’.

.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.