Local elections 2019: the directly elected mayoral contests

On Thursday, 2 May, local government elections are being held across England. At the same time, many voters will also be able to vote for a directly elected mayor to lead their council or metropolitan area. Elections for these mayoralties use the supplementary vote electoral system. The Democratic Audit team explains how these elections work, what will be on your ballot paper, and what we know about candidates’ prospects in each area.

Middlesbrough Town Hall. Picture: Paul Hudson/(CC BY 2.0) licence

This week there are council seats up for election in 248 English councils (plus Northern Ireland’s 11 local councils). Overall in England, the Conservatives are forecast to do particularly badly, partly as this set of council seats were last up for election on the same day as the 2015 general election, an electoral high-point for the party when they won 59% of the council seats contested, and partly because the expectation is the Tories will be punished for the Brexit impasse. However, for the mayoral elections taking place the prospects are slightly different. This is partly because of where they take place – none are currently held by Conservatives – and also because the system focuses on individual candidates and so has encouraged independent and local party candidates, who have had considerable success in previous contests.

Directly elected mayors were introduced to England in 2000, with the system used in London made available as an option for electing an executive leader of all local councils, either established via local referendum or (since 2007) simply introduced by the council. Currently there are 16 such mayors of local councils. In 2017 directly elected mayors were also introduced to oversee six metro and regional combined authorities, including Manchester, Liverpool and the West Midlands, with Sheffield City Region joining the club in 2018. The eighth such post, the mayor for the North of Tyne combined authority, will be elected for the first time this year.

How does the electoral system work?

No voting system for a single powerful office (such as a mayor, governor or president) can operate in a proportional way. Instead the supplementary vote electoral system is used in England, which tries to involve as many voters as possible in deciding who becomes the winner. The ballot paper features two columns, one for voters’ first choice and one for their second choice. They put an X vote against their chosen candidate in the first preference column, and then (if they wish) an X also in the second preference column. Initially, only first preference votes are counted. If any candidate receives more than 50% at this stage they are elected straightaway, and counting ends.

However, if no one wins majority support, the top two candidates go into a run-off stage on their own. All other candidates are knocked out of the race at the same time, and the second preference of their voters are checked on the ballot papers. Second choice votes for the two candidates still in the race are added to their piles. Once all relevant second votes are added in, whoever of the two top candidates has the most votes overall is the winner.

This process of knocking out all the low-ranked candidates at once, and redistributing their voters’ second choices, ensures that the largest feasible number of votes count in deciding who is elected. The person elected can only be one of the initial top two runners (unlike the alternative vote system, rejected at the 2011 referendum), and they always have a majority of eligible votes cast.

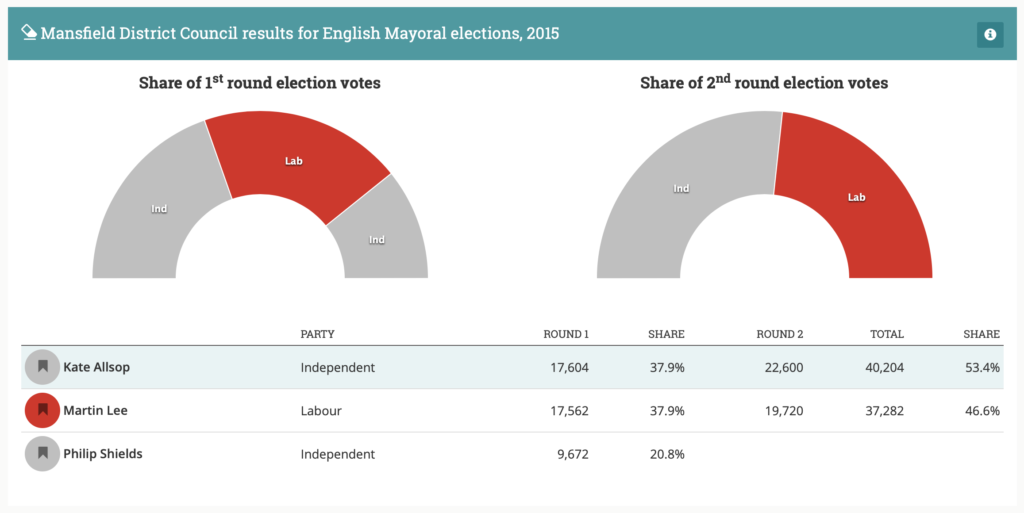

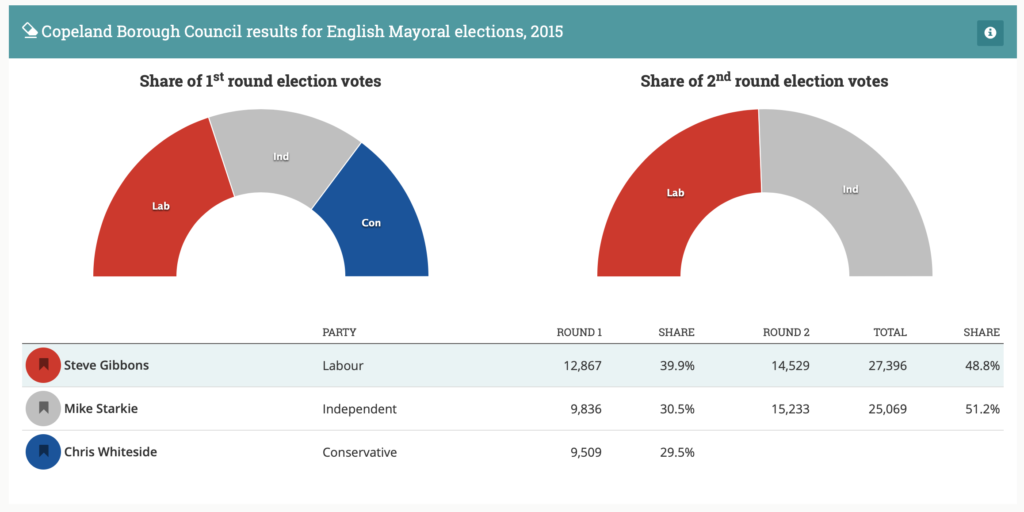

In 16 out of 36 SV contests since 2009 in conventional local authorities, one candidate won outright at the first-preference vote stage, so that second votes did not need to be counted. However, as can be seen from past Mansfield and Copeland results (see below), second preference votes can be decisive. The proportion of voters shaping elections (by casting either a first or second vote for one of the top two candidates) has generally been high in both local council and metro mayoral contests.

Where are mayoral elections happening in 2019?

There are five directly elected local authority mayoral leader elections taking place in 2019: Bedford, Mansfield, Leicester, Copeland and Middlesbrough.

Among these five contests, the result in Leicester looks most certain. Leicester has had a directly elected mayor since 2011, during which time Labour’s Peter Soulsby has been the incumbent. In both 2011 and 2015’s elections, Soulsby won over 50% of first preference votes alone (which means there is no transfer of preferences in a second round). Candidates this time include Baroness Sandip Verma (Conservative), as well as representatives of UKIP, Green, Lib Dems, Socialist Alternative, and an Independent. However, this looks set to be a Labour hold.

In Bedford too, which has had a directly elected mayor since 2002, a win for the incumbent looks likely. The mayoralty was held by independents, the Better Bedford Party, for the first two elections, but it was taken by the Lib Dems in a by-election in 2009 and subsequently held by the party in 2011 and 2015. Incumbent Lib Dem Dave Hodgson led in first preference votes, and comfortably won on the second round thanks to transfer votes from other supporters. Dave Hodgson again looks likely to win this year, and is standing against Labour’s Jenni Jackson, and Conservative Gianni Carofano, plus UKIP, For Britain and Green candidates.

Source: Democratic Dashboard

Previous results have been somewhat closer in Mansfield. The post has been held by the Mansfield Independent Forum since its creation in 2002, first by Tony Egginton from 2002 to 2015, and Kate Allsop since 2015. However, results in 2011 and 2015 have been close. The result in 2015 was decided by only a few thousand votes, as the Independents relied on second round transfer votes to win after finishing behind Labour in the first round (see Figure above). Mansfield Independent Kate Allsop will be hoping to retain the mayoralty next month, as she stands against Labour candidate Andy Abrahams and Conservative George Jabbour, as well as two other Independents.

Source: Democratic Dashboard

Copeland’s incumbent mayor Mike Starkie is also an Independent, having won the first election to the position in 2015. He came from second place on 30.5% in the first round to first place on 51.2% in the second round, by taking more of the third-placed Conservative candidate’s second preference votes than Labour, who ultimately came second. Standing against him this time is Linda Jones-Bulman for Labour and Conservative Ged McGrath. Mike Starkie will be hoping to secure enough second preference votes from Conservative supporters to retain the position this year.

Middlesbrough has had a directly elected mayor since 2002. Independent Ray Mallon held it from 2002 to 2015 (winning in each election with more than 50% of the first preference votes). In 2015, Labour candidate Dave Budd took it on second preference votes, beating independent Andy Preston. Dave Budd is standing down this time, however, and is replaced as Labour candidate by Mick Thompson. The Conservative candidate is Ken Hall, and Andy Preston is standing again as an independent. Though Labour has a clear majority on the current council, popular scepticism with established parties and their leaders is currently running high, and the mayoral race was a tight contest last time, with only 0.6% between Preston and Labour after second preferences were counted. As such, Middlesbrough is likely to be the race to watch in 2019.

North of Tyne

This new combined authority area covers Newcastle, North Tyneside and Northumberland, and it is electing its mayor for the first time. Labour’s Jamie Driscoll will be favourite to win the mayoralty, as the party controls both North Tyneside and Newcastle local authorities. Other candidates include John Appleby (Liberal Democrats), Charlie Hoult (Conservatives), William Jackson (UKIP), and John McCabe (Independent). One thing is certain from this list: whoever wins, still none of England’s eight combined authority metro-mayors will be women. (There are currently only four female directly elected mayors in England out of 24, all representing single local authorities.)

NB. The explanation of the SV vote is adapted from The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Chapter 2.2 ‘The reformed electoral systems used in Britain’s devolved governments and England’s mayoral elections‘, by Patrick Dunleavy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.