Strategic voting in the 2015 general election: why Liberal Democrats didn’t vote for their own party

When do people not vote for their preferred party? Isaac Hale finds that in 2015, Liberal Democrat supporters abandoned the party when they thought it had no chance of winning a seat and a tactical vote could affect the outcome in their constituencies. This shows how in a first-past-the-post electoral system smaller parties can be caught in a vicious cycle of low expectations and strategic voting by their supporters.

Nick Clegg with Lorely Burt in Solihull for 2015 general election campaign. Picture: Liberal Democrats/(CC BY-ND 2.0) licence

Why do voters sometimes vote for a candidate who is not their first choice? Often, it is because they believe that their preferred candidate has no chance of victory. Political scientists refer to this phenomenon as ‘strategic voting’. Any time voters make choices based on their expectations about the results of an election as well as their sincere candidate preferences, strategic voting is taking place.

The cause of strategic voting is fundamentally psychological: voters are averse to ‘wasting’ their votes on parties who are unlikely to emerge victorious in their electoral district. In countries like the UK, the US or Canada that use a first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system the single district-level victor emerges with all the spoils – there are no proportional mechanisms that could encourage voters to stick strategically with their preferred candidate. In such a system, we should expect to see strategic voting among people who sincerely prefer candidates and parties they think are not among the top-two competitors in their district.

Despite the intuitive appeal of strategic voting, there is mixed evidence that it actually occurs. The 2015 UK general election was the perfect opportunity to collect new evidence. Because of the dramatic negative shift in fortunes for the Liberal Democrats, which was widely publicised during the lead-up to the election, the behaviour of Liberal Democrat voters in the 2015 general election is a most likely case study for strategic voting. There is evidence that the British public was well aware of the doomed fate of the Liberal Democrats in the run-up to the 2015 election and understood that the following government would likely be formed by either the Conservatives or Labour. Additionally, the two largest parties in the UK are quite polarised, making voter indifference between them less likely.

In an article recently published in Parliamentary Affairs, I test whether Liberal Democrat voters in the 2015 UK election voted strategically for Labour and Conservative candidates to maximise their odds of affecting the electoral outcome in their constituency. Drawing on data from the British Election Study (BES), I calculate two quantifiable predictors of strategic voting, both of which derived from each voter’s perceptions of the likelihood of each party winning the seat in his/her own constituency. The first variable (‘no chance’) indicates how far behind voters perceive the Liberal Democrats to be relative to the party they perceive to be most likely to win. The higher the value of this variable for a Liberal Democrat voter, the more certain they are that their party will lose in their constituency – and thus the more likely it is the voter will vote strategically for another party’s candidate.

The second independent variable that my analysis centres on can be thought of as ‘closeness’. This variable indicates how close the race between the Labour and Conservative candidates is in the constituency of the voter. Higher values of ‘closeness’ indicate the voter perceives the difference in the likelihood of victory between the Labour and Conservative candidates in their constituency to be closer. As the race between those two candidates gets tighter, voters should be more likely to vote tactically for one of them, contingent on the Liberal Democrat having a sufficiently high ‘no chance’ score.

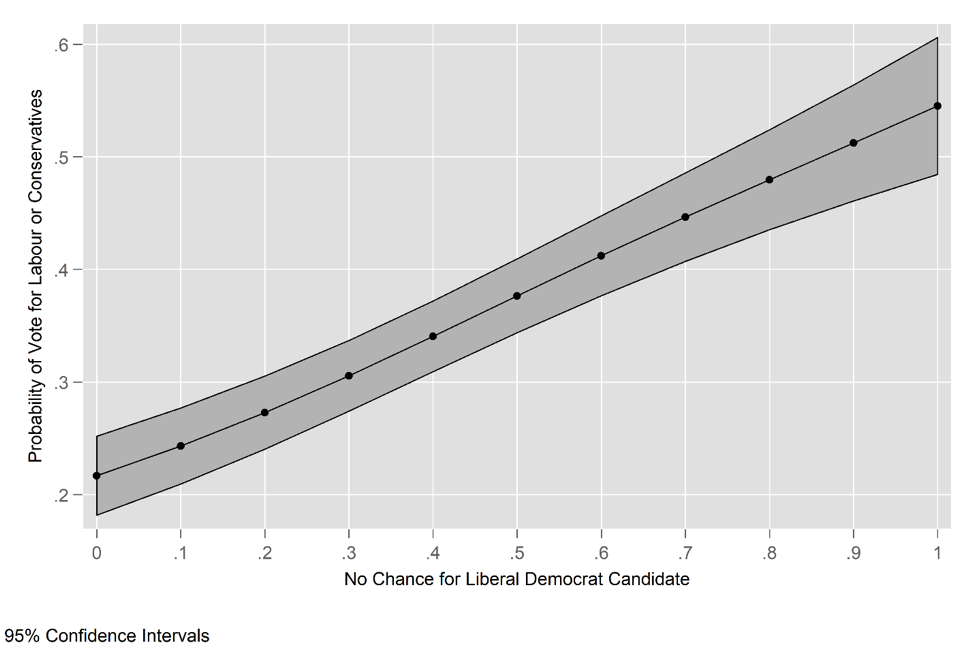

The key findings of this study are presented in Figures 1 and 2, which show the probability of a Liberal Democrat voter engaging in strategic voting in 2015. Figure 1 shows the effect of perceptions of the likelihood of the Liberal Democrat losing in the voter’s constituency (‘no chance’) on his/her probability of voting strategically for a Labour or Conservative candidate.

Figure 1: Probability of strategic voting of Liberal Democrat supporters by ‘no chance’ perceptions

As we can see, Liberal Democrat voters’ chances of strategic voting increased as their belief that the Liberal Democrat candidate will lose increases. When the Liberal Democrat candidate is perceived to be the most (or tied for most) likely to win (a no chance score of 0), 22% of Liberal Democrat voters are still expected to defect. However, when the Liberal Democrat candidate is perceived to have no shot at winning (a no chance score of 1), 55% of Liberal Democrat voters are expected to defect – a 33-point increase.

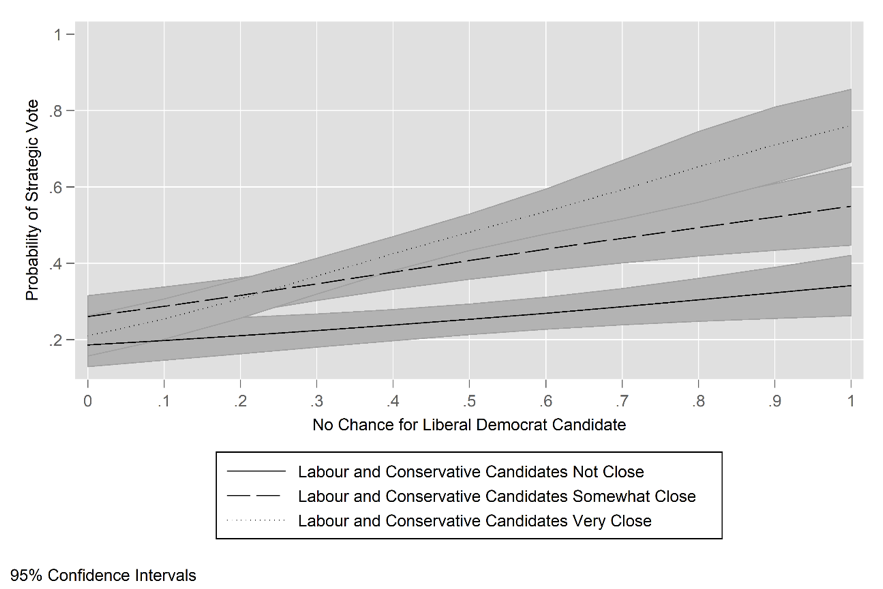

However, the magnitude of this effect is conditioned by how close the Liberal Democrat voter thinks the race is between the Labour and Conservative candidates in their constituency (‘closeness’). Each line in Figure 2 corresponds to a different group of Liberal Democrat voters: those who perceived the race between the Labour and Conservative candidates in their constituency to be either close, somewhat close or not close.

Figure 2: Probability of strategic voting of Liberal Democrats by ‘no chance’ and ‘closeness’ perceptions

While the probability of strategically voting barely increases as ‘no chance’ increases, when either the Labour or Conservative candidate is perceived to have no shot at victory (a ‘not close’ race between the Labour and Conservative candidates, represented by the solid line in Figure 2), the probability increases more noticeably when the two-party Labour–Conservative likelihood of victory margin is perceived to be close (the ‘somewhat close’ dashed line in Figure 2), and the odds of strategic voting increase dramatically when the Labour and Conservative candidates are perceived to have similar odds of winning the constituency (the ‘very close’ dotted line in Figure 2). This plot shows that the effects of ‘no chance’ and ‘closeness’ on strategic voting are multiplicative. When the Liberal Democrat candidate is perceived to be inviable and the race between the Labour and Conservative candidates is perceived to be close, the probability of strategic voting among Liberal Democrats is highest.

This research provides additional insight into the causes of the Liberal Democrats’ electoral rout in 2015. While some Labour and Conservative voters may have ‘come home’ in 2015 after supporting Liberal Democrat candidates in 2010, Liberal Democrat voters were also reluctant to continue supporting their party when they believed such support would result in a wasted vote. The Liberal Democrats appear to have been caught in a vicious cycle of negative public perception: ominous polling and souring attitudes towards leader Nick Clegg lowered expectations of the party’s performance in the election and these lowered expectations in turn further drove down voter support for the party – even among its own partisans.

In summary, Liberal Democrat voters acted strategically and were reluctant to waste their votes when they clearly perceived their own party to be inviable and believed their vote could affect the outcome among the alternative parties. More generally, when a party’s chances take a nosedive in the public eye, we should be on the lookout for strategic voting from that party’s previous supporters. We should expect strategic voting to be particularly likely in countries like the UK that use majoritarian voting systems (like FPTP) but have a fragmented, multi-party system.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s article, ‘Abandon Ship? An Analysis of Strategic Voting among Liberal Democrat Voters in the 2015 UK Election’ published in Parliamentary Affairs.

About the author

Isaac Hale is is a doctoral candidate in Political Science at the University of California, Davis. His research focuses on electoral systems, legislative representation, political behaviour and public opinion.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

To their credit, the LibDems have always understood this – which is why they have hisotrically made such a show (when able) to turn the tables on the argument and point out in campaigning literature that “only the LibDem can beat the Conservative/Labour candidate here”. This is also not new and works against the other parties too. Immediately after the 1997 landslide for Labour, there was effectively a re-run of a contested seat (Winchester) where the Tories and LibDems had almost tied. In that by-election, still high in the polls, Labour lost its deposit, having at the General Election itself achieved over 10% of the vote.

The history of Westminster voting in Scotland from the late 1960s, and specially in those two General Elections of 1974, gave us all a taste of what could emerge: if the Brexit Party catches the time right (Peterborough by-election and Europarl Elections), it could almost overnight establish that fourth force in English politics which UKIP occupied briefly for half a decade before it supposedly “achieved what it had been campaigning for”…