Elections to the European Parliament: what if more people voted?

Can the rise of Eurosceptic and extremist parties be blamed on the mobilisation of people who previously had abstained from the polls? An analysis of the 2009 and 2014 elections to the European Parliament suggests that support for Eurosceptic parties would be largely unaffected by changes in voter turnout, write Uwe Remer-Bollow, Patrick Bernhagen and Richard Rose. Extremist parties would even have lost vote shares if turnout had reached the higher levels observed at national general elections.

European Parliament, Strasbourg. Picture: © European Union 2018 – European Parliament/(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Turnout at elections to the European Parliament (EP) is much lower than at national general elections. But while EP election turnout has decreased continuously since the first direct elections in 1979, the trend slowed down and almost came to a halt at the 2014 elections. These elections also saw a surge of Eurosceptic parties, and some commentators have linked increased voter participation to gains for extremist parties. Recently, researchers at the European Council on Foreign Relations have suggested that higher voter mobilisation at the 2019 European Parliament elections might lead to the views of a silent pro-European majority getting drowned out when the new parliament gets elected between 23 and 26 May 2019. While turnout might indeed matter, our analysis shows that increased participation might instead actually harm extremist parties.

Why should turnout matter at European Parliament elections?

EP elections are second-order national elections, where vote choices are primarily based on domestic political conflicts and debates. At these elections, turnout is much lower, so any increases in voter participation can potentially have much larger consequences for candidates and parties. Across the 2014 EP elections, the average turnout rate was 24 percentage points lower than average turnout at the most recent general elections in the member states (in 2009, the difference was 25 percentage points). Moreover, at EP elections, extremist parties tend to perform well, as large and moderate parties find it more difficult to maintain the mobilisation levels of their supporters. Extremist parties are also frequently the ones that hold the clearest Eurosceptic positions. Far-right parties oppose European integration on the grounds of national identity and sovereignty being threatened by the EU, while far-left parties object to the neoliberal character of the European project. However, attitudes and positions on European integration form a distinct policy dimension of its own, and some Eurosceptic parties, such as the Christian Union in the Netherlands, are not particularly extremist in terms of left–right ideology.

The 2007/2008 financial and economic crisis and its consequences have given a boost to Euroscepticism. While the 2009 EP election has seen only modest, if any, gains for Eurosceptic parties, their vote shares increased considerably at the 2014 elections. Since this took place against a backdrop of nearly stagnant voter turnout, it is tempting to conclude that Eurosceptic and extremist parties would benefit from a mobilisation of erstwhile non-voters. To find out whether they would, we have to estimate how non-voters would vote if they decided to become voters.

Higher turnout would strengthen the left and the centre

Using survey data from the 2009 and 2014 European Election Studies, we estimated party vote shares at increased turnout levels. To this end, we simulated the vote choice for each self-confessed non-voter based on their sociodemographic characteristics and political attitudes. We then added these simulated votes to the observed votes until a higher turnout rate was reached, starting with those most likely to be mobilised and correcting for any over-reporting of turnout and misreporting of party choice by survey respondents. As a plausible higher turnout rate, we chose the turnout at the most recent general election in each member state, which takes into account country-specific voter mobilisation.

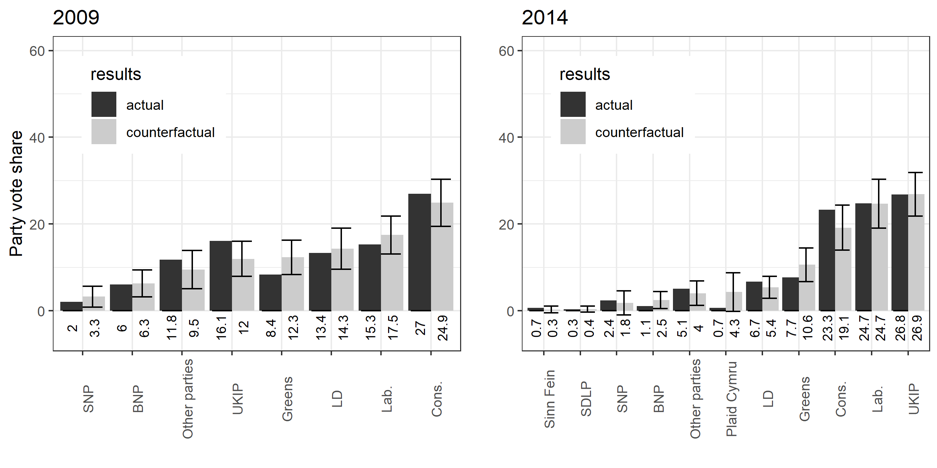

For about one-third of all parties, higher turnout would have made no difference to their vote share in 2009 or 2014. Yet, some parties would have experienced considerable gains and losses. Figure 1 shows the turnout effects at the 2009 and 2014 EP elections in the UK. The dark grey bars show the parties’ vote share according to the survey data, and the light grey bars indicate the simulated vote shares that we would expect if turnout had been as high as at the 2005 and 2010 UK general elections, respectively. The thin error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals and reflect that some of the votes are simulated rather than reported. In 2009, higher turnout mainly would have benefitted the Green Party, while UKIP would have lost vote shares. Any gains and losses for the other parties are not statistically significant. For the 2014 EP election, none of the estimated party vote changes are statistically significant, although the Greens and Plaid Cymru come close and might have each gained about 3 percentage points.

Figure 1: Vote shares of UK parties at the 2009 and 2014 EP elections: Actual results and simulations of counterfactual higher turnout

Note: Differences in the number of parties included are due to data availability.

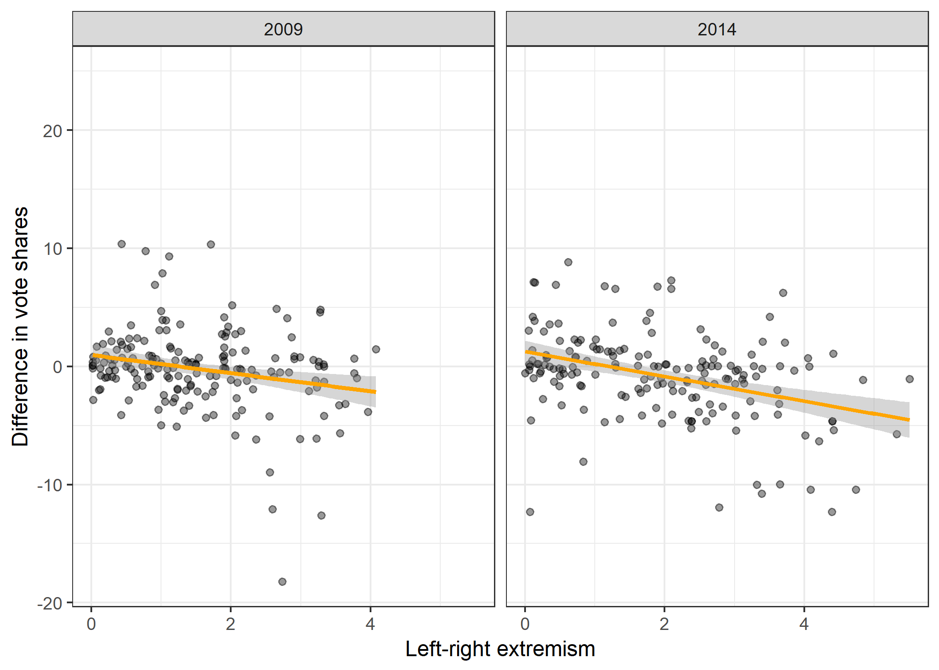

Analysing the effect of turnout on the vote shares of all parties across the EU, we found that leftist parties as well as moderate parties would benefit significantly from higher turnout. With each point that a party moves away from the moderate end of the 6-point scale of left-right-extremism, it would have lost 0.75 percentage points of its vote share if turnout at the 2009 EP election had been as high as at the most recent previous national general election (0.65 percentage points in 2014, see also Figure 2). However, parties’ positions on European integration on its own is unrelated to voter turnout. Finally, parties that are both Eurosceptic and extremist would have benefited somewhat from higher turnout at the 2014 elections, but not in 2009.

Figure 2: the negative effect of higher turnout on extremist parties

In sum, because so few people vote at EP elections, there is considerable scope for higher turnout to make a difference for parties’ vote shares. On average, right-wing parties and extreme parties would have suffered under a scenario of higher turnout both in 2009 and in 2014. On the basis of these findings, leftist and moderate parties would be well advised to intensify efforts at getting out the vote. Taking these effects into account, Euroscepticism per se would be neither boosted nor contained by changes in voter turnout, although extremist Eurosceptic parties would have slightly benefited from higher turnout in 2014. Readers should bear in mind, however, that higher turnout might have consequences other than those predicted by our analysis. First, if parties would expect higher turnout at the 2019 elections, they might re-direct there campaign efforts to gain the support of newly mobilised, yet undecided voters. Second, any stimulus capable of mobilising hitherto passive citizens might at the same time make them reflect on their partisan inclinations. Across the EU, our findings suggest that extremist parties would have strong incentives to try and appeal to a larger pool of electors if turnout went up, as they would otherwise lose vote shares. Finally, the resulting incentives for all parties to work harder, both at mobilising additional voters and appealing to the undecided, would strengthen the representational ties between European citizens and elites.

This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of Democratic Audit. It draws on their article ‘Partisan consequences of low turnout at elections to the European Parliament‘, published in Electoral Studies.

About the authors

Uwe Remer-Bollow is a Researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences,

Department of Political Systems and Political Sociology, University of Stuttgart.

Patrick Bernhagen is Professor of Comparative Politics and Head of the Department of Political Science and Political Sociology at the Institute for Social Sciences, University of Stuttgart.

Richard Rose is Professor of Politics and Director of the Centre for the Study of Public Policy, University of Strathclyde.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] elections to the European Parliament‘, published in Electoral Studies. It first appeared on the Democratic Audit. Image: European Parliament, Strasbourg. Picture: © European Union 2018 – European […]

My comment has disappeared after being up earlier, so I will try again – your use of the word ‘extremist’ to describe parties of which you disapprove is inflammatory and unacademic. To use such words is dangerous and irresponsible without explaining what you fully mean by ‘extremist’ and who you specifically are talking about. Failure to do this is both cowardly and wrong, and an attempt to smear your political opponents. Your article makes a good point about what might happen in the event of higher turnout, but is rendered invalid by its fake news style approach to those the authors do not agree with or disapprove of. As I said before, try again and remove your emotions from the piece…

Dear Mr. Hockney,

Thank you for your interest in our article. Our measurement of extremism is based on the left-right ideological position of a party, which is standard practice in political science research on elections and parties. To gauge that position we averaged the left-right-placement that respondents to the European Election Studies Voter Survey gave for each party of their party system on an 11-point scale. Thus, rather than imposing our own perceptions of parties’ ideological stance, we use those of the survey respondents (1,000 randomly selected citizens in each EU member state). To measure ideologically extreme positions, we fold this left-right scale at the midpoint (5). As a result, parties are coded as more extreme, the closer they are to either the left or the right end of the ideological spectrum. Using this method, we coded 180 parties for the 2009 EP elections and 172 parties for the 2014 election. We cannot list all these parties and their scores here. However, to illustrate, at the 2014 European Parliament election in the United Kingdom, UKIP was coded an extreme-right party by this measure. No extreme-left party contesting that election in the UK was large enough to escape the category of “other parties”, and for that category we did not code left-right positons as it contains very different parties. We fail to see how this measurement of extremism has anything to with cowardice, emotions, or the approval or disapproval on our part of any of these parties. Further details are provided in the full research article and the associated extensive online appendices.

Sincerely,

Patrick Bernhagen