Representing interest groups: umbrella organisations enjoy preferential access to the legislative arena but not to the media

Lobbying for access to parliamentary and media debates potentially allows organisations to represent the interests of their members and exert political influence. Wiebke Marie Junk looks at which types of interest groups are favoured when it comes to lobbying access in the United Kingdom and Germany. She finds that access to the legislature is higher for ‘umbrella’ organisations that unite many member groups, while representing a higher number of individual people does not seem to matter.

Photo by Craig Whitehead on Unsplash

Many interest groups today function as highly complex machineries of political representation. The UK Chamber of Shipping, for instance, presents itself as the ‘voice of the UK shipping industry’, bringing together professional organisations and associations of shipowners to organise the interests they have in common. Similarly, the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) joins eight trade unions spanning diverse sectors from metalworkers (IG Metal) to the union of service providers (ver.di), and claims to represent the voice of all these unions to political decision-makers. Jointly the unions in the German Trade Union Confederation represent roughly six million individual members, meaning a number of people comparable to the entire population of Denmark.

Political parties that compete in elections are therefore not the only actors promising to organise and represent diverse economic and societal interests in our modern democracies. However, when it comes to interest groups and their ‘umbrella organisations’, which is what we call the parent organisations that unite many national or subnational member groups, it is harder to assess the extent to which they successfully or rightfully offer voice to the interests they represent.

In a recent article in the journal Governance, I analyse how a sample of 286 interest groups gain a voice in political discussions on twelve concrete policy issues in the UK and Germany. More specifically, I look at which of the active groups on the issues 1) have access to a legislative hearing in parliament and/or 2) have access to media debates by getting a say in print newspaper articles on the specific issue.

What I was especially interested in was to assess whether ‘umbrella’ organisations like the UK Chamber of Shipping or the German Trade Union Confederation have advantages in getting access to parliamentary and media debates. By extension, this would mean they have a bigger chance to affect policy discussions and outcomes and, therefore, are more powerful players in policy processes today than organisations that have no member groups. At the same time, I wanted to probe whether umbrella organisations gain access depending on the number or scope of their member organisations, or rather because of the number of individual citizens that are direct members or supporters of the organisation, or which the interest group claims to represent more indirectly.

My results show two important patterns: firstly, I do not find evidence that claiming to represent a higher number of people – either direct members or indirect constituents – has a positive effect on access to parliamentary hearings or on media debates on the sampled issues in the UK and Germany. Secondly, I find that that representing member organisations matters a great deal more. Yet interestingly, access to media debates and access to parliamentary hearings function by different logics in this regard and therefore benefit different types of interest organisations. In short: while umbrella organisations enjoy higher legislative access, they have less voice in media debates.

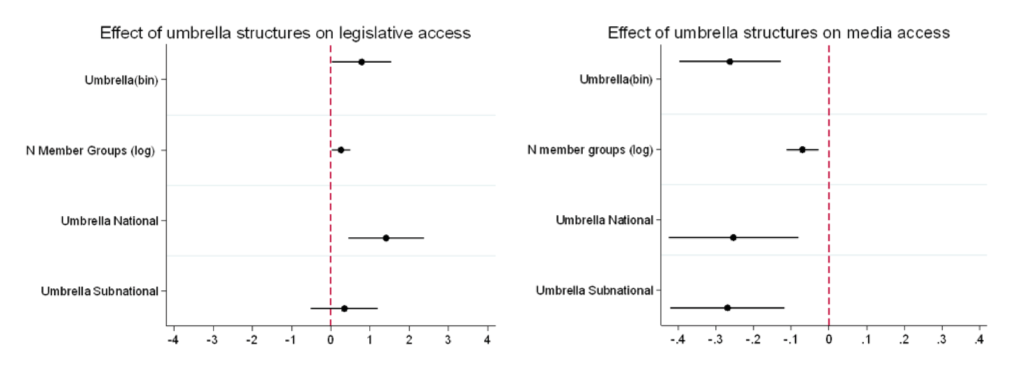

Figures 1 and 2 visualise selected coefficients in my regression analyses and show that media and parliamentary access are essentially mirror images of each other when it comes to giving voice to umbrella organisations. The figures show the estimated positive or negative effects of different measures of umbrella structures: these include the mere status as an umbrella, its size in terms of the number of member groups, and the national or subnational scope of the umbrella. Irrespective of which measure I chose, I find a strong general pattern of a reversed access logic in the two arenas of policy discussion.

As regards parliamentary access, the effect is positive and we see that (especially larger and national) umbrellas enjoy significantly higher access to legislative hearings. In contrast, there is a robust negative effect in the media, which means that (larger, national and subnational) umbrella organisations have lower media access than interest groups without member organisations.

Figures 1&2: Coefficient plots of the effects of umbrella structures on legislative and media access

Note: Plots show the coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals estimated based on the main models (1–6) in the journal article. Note that estimations are made for different operationalisations of umbrella structures to measure whether the mere status as an umbrella (Umbrella bin), the size of the umbrella (N member Groups log) and its scope depending on whether member groups are only subnational or also national organisations (Umbrella Subnational and Umbrella National) affect lobbying access positively or negatively. For more information on the models and operationalisation of variables, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

These patterns make sense from a perspective of enhancing efficient consultation in parliamentary hearings. Umbrella organisations that unite the views of many member organisations should be an asset: they can provide pooled expertise from their member groups, increase input legitimacy and may ease future policy implementation by pledging cooperation of many member organisations. Conversely, it seems that the characteristics that aid legislative voice are a hindrance in the news media. This can be explained using theories of how ‘news value’ is generated. From this perspective, aspects that increase the appeal of a news story are for instance personalisation, audience identification, and negativity. In these respects, umbrellas are unlikely to have systematic advantages – or may even have disadvantages – compared to organisations without member associations.

These findings shed important new light on political representation through interest groups. While groups do not seem to gain access and voice based on the numbers of individual members or constituents they claim to represent, their organisational membership matters as an access good in the legislative arena. Practically, this may make consultation processes more efficient. Normatively, we can ask what biases – potentially in favour of larger, well connected, and professionalised organisations – this introduces into the policy process.

It is worth noting, however, that my analysis in limited in the sense that it cannot tell apart the extent to which the patterns are driven by the behaviour of legislators and journalists or by interest groups themselves. Do umbrella groups target the legislature, whereas their member organisations target media debates, when jointly trying to affect policy? My findings may also be explained by such a division of labour between interest groups, where umbrellas and their member groups act like differentiated organs of complex bodies of interest representation, targeting different institutions in our political systems. I hope that future research can attend to these roles of both individual and highly networked interest groups in policy discussions and decision-making.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit. It draws on the article ‘Representation beyond people: Lobbying access of umbrella associations to legislatures and the media‘, published in Governance.

About the author

Wiebke Marie Junk is a Postdoc at the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen and a member of the GovLis Project (‘When does Government Listen to the Public?’) on political responsiveness to citizens and interest groups.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.