Do early elections provide a financial advantage for parties in power?

If parties in power have the discretion to call an election when they wish, rather than being restricted to fixed electoral terms, do they have an advantage in terms of raising campaign funds? Looking at the case of Denmark, Lasse Aaskoven finds that they do, which could have implications for the UK, and its rules about electoral terms.

In most Western parliamentary democracies, the incumbent government has the ability to call early elections before the official electoral term is over (though the specifics of a government’s election-calling power can vary). Early elections were for a long time a core feature of British political system until the Fixed-term Parliaments Act of 2011 removed the government’s discretionary power to call elections. However, as the 2017 British general election (and current speculation) shows, early elections may not be a thing of the past for British politics. In other parliamentary democracies, such as the Netherlands and Denmark, early elections have also been prevalent in the post World War II period.

Research into the causes and consequences of these early elections have mainly focused on the government’s strategic incentive to call early elections, as well as their electoral consequences. One of the core questions within this area is whether the government can increase its chance of re-election through its ability to determine when an election takes place, for example by choosing to call one when opinion polls are favourable to them and/or when the economy is doing well, or whether voters react negatively to early election-calling and view them as a sign of government opportunism and/or lack of competence, as well as indicating worse expectations for future performance.

However, might early elections also provide a relative advantage to the incumbent party or parties with regards to raising private campaign contributions? In most countries, especially the UK, private contributions from actors such as trade unions, employers’ associations, private firms and individuals are an important part of funding political parties and their electoral campaigns. While the specific electoral consequences of these private campaign contributions are still up for debate, there is no doubt that political parties view such donations as important and spend time and energy raising private funds.

In a recent research article in Acta Politica, I investigate the link between early elections and private contributions to political parties using data from Denmark between 1991 and 2013. While there are significant differences between Denmark’s political system and the UK’s, including frequent coalition governments, a proportional system of representation and relatively generous public funding for political parties, it also shares similarities, including a parliamentary system of government and a tradition of close financial ties between political parties and organisations such as trade unions (mainly on the centre-left) as well as private employers’ associations and private firms (which usually donate to the main centre-right parties).

I hypothesise that early elections provide incumbent government parties with a financial advantage relative to opposition parties for two reasons. First, in most cases the government will know well before opposition parties that an early election is coming. This might enable the government parties to contact and signal to their private donors that they should antedate their contributions to the government parties, since these parties will need these funds sooner than previously expected. On the other side, donors to opposition parties will have the funding for their party budgeted mainly for the year in which the government’s term formally expires. Furthermore, a government party that knows an early election is coming has more time to activate their members and fundraisers, which might also help them raise more private contributions during early elections than opposition parties. These factors should give the incumbent government parties a relative financial advantage in early election years, especially if the electoral campaign is fairly short.

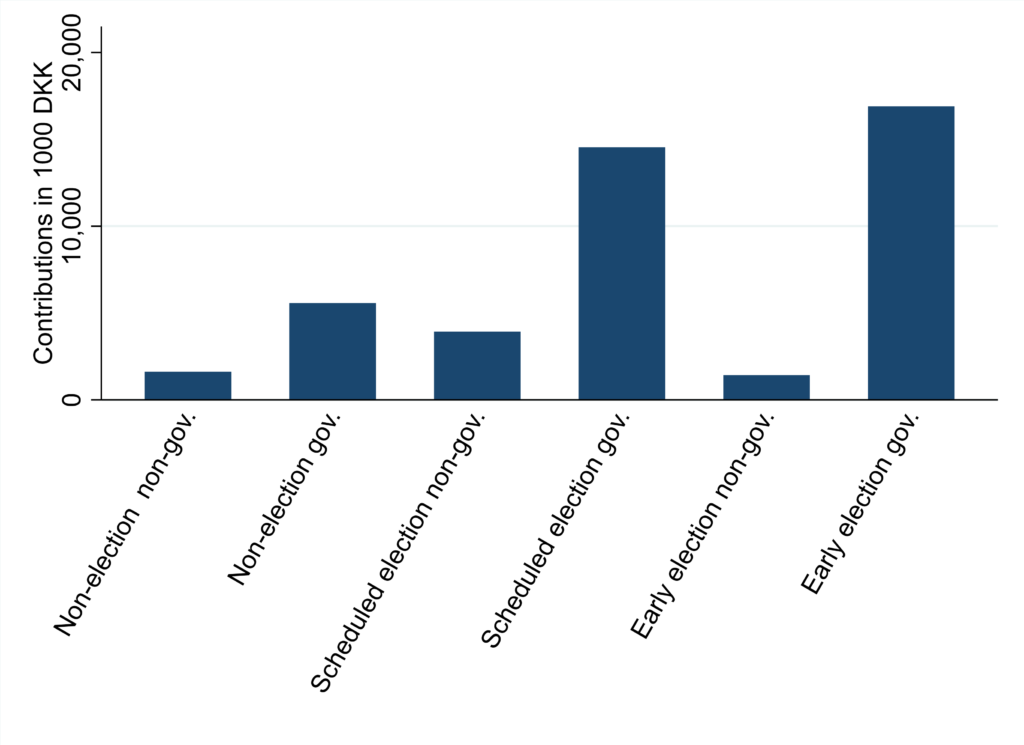

I test this hypothesis on the Danish party finance data using statistical methods. In simplified terms, in Figure 1, I show the average level of private contributions (in 1000s of DKK) to Danish political parties split by whether the party is in government and whether the year in question is a non-election year, a scheduled election year (held close to the time the government’s term formally expires) or an early election year.

The trend in this data provides substantial evidence in favour of the hypothesis. All types of parties seemed to have received more private contributions in scheduled election years relative to non-election years. Government parties also seemed to have received more private contributions than other parties in all types of years. However, the relative advantage for government parties with regards to private contributions was much higher in early election years compared to scheduled election years. In early elections years, non-government parties received a much lower level of private contributions compared to scheduled election years, while government parties received a slightly higher level of private contributions. Early elections thus seemed to have provided Danish government parties with a relative financial advantage.

Figure 1: Average private contribution to Danish parties 1991–2013

In Denmark during the period from 1991 to 2013, early elections seemed to have provided government parties with a substantial relative financial advantage. While there are differences between Denmark and the UK, one might still speculate about whether some of the same mechanisms might be a play in British politics. The question then naturally arises as to whether the Fixed-term Parliaments Act of 2011, to the extent it will actually lead to more predictable electoral cycles, will have limited this potential advantage? Any future discussions about the desirability of the government’s discretionary election-calling power, both in the UK and other democratic countries, should at least consider the potential advantage for government parties relative to the opposition in raising private funds ahead of any early elections they call.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s article, ‘The electoral cycle in political contributions: the incumbency advantage of early elections’, published in Acta Politica.

About the author

Lasse Aaskoven is Lecturer at the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.