Why do ‘niche parties’ perform so well in European and subnational elections?

Single-issue parties, such as the Brexit Party and Greens, tend to do better in local and European elections across Europe. Emmy Lindstam examines why, and finds that voters are willing to vote switch on an issue they think is overlooked by their preferred party, particularly if they think the stakes are low for that election.

Picture: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Nordrhein-Westfalen / (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence

The recent European elections saw a range of small, single-issue parties perform exceptionally well. In the United Kingdom, the Brexit Party received 30.7% of the votes. In Germany, the Green Party made remarkable gains, winning 20.5% of the votes. Green parties also performed well in countries such as France, Sweden and Finland, as did anti-immigration far-right parties. Although these strong results may be viewed as inevitable consequences of fragmenting party systems linked to the growing importance of issues such as climate change, immigration and national pride in public debate, these results in fact fit a longstanding pattern: single-issue parties – sometimes referred to as ‘niche parties’ – tend to receive higher vote shares in European and subnational elections (so called ‘second-order elections’) than in preceding and subsequent national elections. Why is this the case?

Political scientists have long shown an interest in the motivations guiding vote switching between electoral arenas. Many of these explanations have to do with the notion that voters think there is ‘less at stake’ in European and subnational elections than in general elections. As a consequence, some propose that voters switch parties in second-order elections because they feel freer to vote sincerely (they experience less pressure to vote strategically for one of the top contenders of the election). Others propose that voters use these elections as a kind of ‘mid-term referendum’, using this less important vote to show dissatisfaction with the national government. Despite a range of aggregate- and individual-level studies pointing to different explanations why voters switch parties in these kind of elections, we know quite little about what explains switching from mainstream parties to niche parties, in particular.

In a recent article in Electoral Studies, I engage directly with this question. Although many different valid explanations may account for this pattern, I focus on a particular potential explanation: voters may switch to niche parties not because they sincerely prefer those parties, but because they hope to signal the importance they attach to a certain, overlooked issue to their preferred mainstream party. Different motivations guide vote choices. While many voters simply vote for the party they want to win, others face a trade-off when deciding how to vote. Their preferred party might be the best option available, but it would be significantly better if it made some kind of policy adjustment. Such voters can either vote for their preferred party or strategically defect to a less preferred party hoping this will reveal their policy preferences and induce a change in their preferred party’s policies.

Why would such ‘signalling’ be more common in European and subnational elections than in general elections? And why would niche parties gain, in particular? To account for this, it can be helpful to think of the costs and benefits of signalling; the cost of voting for a non-preferred party in the present has to be weighed against the potential benefit of the preferred party making a policy change in the future. Certain factors are likely to increase the likelihood that voters’ expected benefit of switching outweigh the expected cost. For instance, the expected benefits of switching should be higher the less voters care about the election outcome in the present. This may explain why motivations to signal are particularly strong in second-order elections where less is generally perceived to be at stake. Moreover, the expected benefit of signalling should be higher the more voters care about future policy change. Mainstream parties tend to mount weaker campaigns leading up to second-order elections than for general elections. Voters might therefore place more relative weight on issues outside of the mainstream parties’ main policy repertoire during such campaigns. Finally, the expected benefit of signalling through a party switch should depend on the perceived probability that the preferred mainstream party will be receptive to the signal, and adjust its policies accordingly. Electoral defections to a party that campaigns almost exclusively on one single issue should be more easily interpretable and more likely to provoke a concrete policy response than defections to a party that campaigns on a range of issues. Voters with incentives to signal policy concerns should therefore be more likely to switch parties when a niche party, rather than another mainstream party, campaigns on the issue the voter cares about.

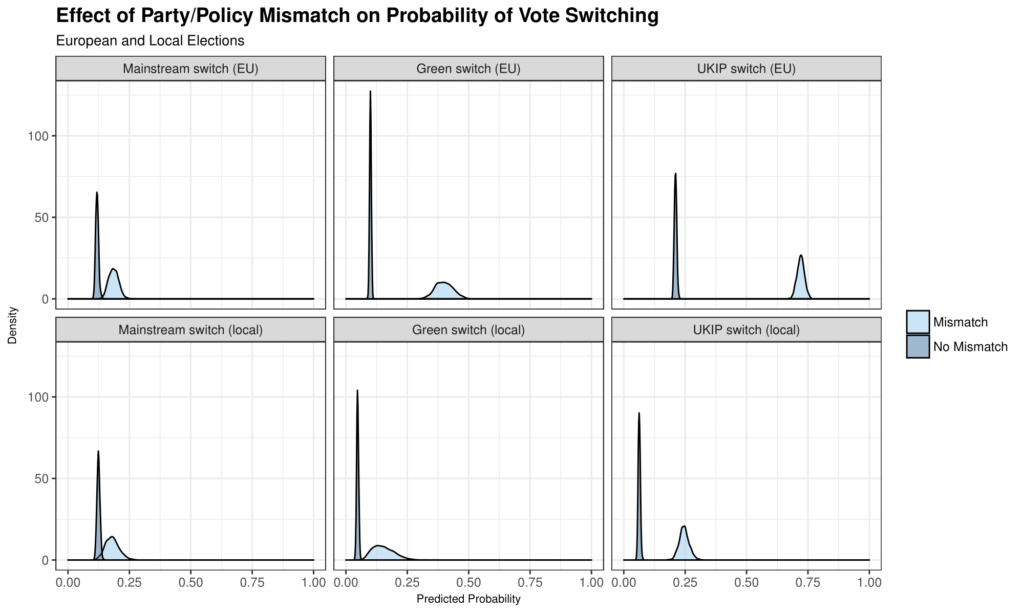

Evidence from the British Election Study Internet Panel lends support to the idea that switching is not driven entirely by sincere preferences over outcomes, but rather by voters’ efforts to signal how much they care about a certain issue. First, many voters who switch to niche parties do not identify with, or much like the party they switched to. The data suggest that 76% of those voters who switched from a mainstream party to UKIP in the 2014 European election and 68% of those who switched to the Greens claim to have voted for a party other than the one they identify with. In the local elections of 2014, 66% of UKIP switchers and 61% of Green switchers did so. The evidence stands in contrast to the idea that voters are switching to their first preference. Second, voters who perceived a mismatch between the party they identify with and a party they name as best at handling an issue of importance to them (those with incentives to signal policy preferences) were particularly likely to switch parties in second-order elections — more so than voters who had other reasons to ‘protest vote’, such as being dissatisfied with government performance, or feeling disillusioned with democracy. Finally, as can be seen in Figure 1, perceiving a party/policy mismatch was much more likely to lead voters to switch if this mismatch was perceived between a mainstream and a niche party, than between two mainstream parties. This suggests that niche parties are particularly likely to attract votes in elections where incentives to engage in signalling are high.

Figure 1: Predicted probabilities of switching given a ‘party/policy mismatch’, European and local elections, 2014

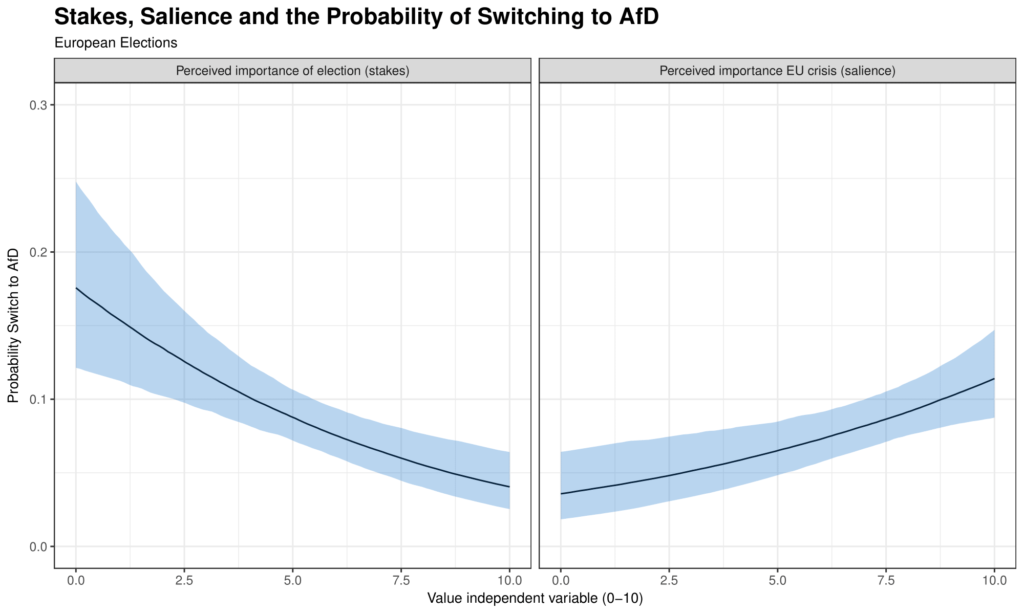

Evidence from a panel study in Bavaria collected by Making Electoral Democracy Work lends additional evidence to the idea that signalling explains niche party switching. In particular, voters who perceive there to be less at stake in European and regional elections become more likely to switch to a niche party in those elections. I also find that voters who place much importance on an overlooked issue, in this case the EU eurozone crisis, become more likely to switch – consistent with the ideas that stakes and issue salience drive incentives to signal (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Predicted probabilities of switching to AfD in the European elections 2014 given changes in perceived stakes and issue importance

Taken together the results suggest that incentives to signal policy preferences are likely to explain at least part of the important niche party gains in European and subnational elections. The fact that the results replicate both in European and subnational elections imply that switching does not correspond only to arena-specific concerns (such as voting on ‘European issues’ in European elections); voters who perceive a mismatch between party and policy preferences are likely to switch their vote in second-order elections, even in elections where the ‘niche issue’ cannot be effectively pursued. In sum, different motivations guide vote choices. Switching parties between electoral arenas may be a way to solve tensions between competing voting motivations among those who are torn between voting for a preferred party and signalling specific policy preferences.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s recent article ‘Signalling issue salience: Explaining niche party support in second-order elections‘ published in Electoral Studies.

About the author

Emmy Lindstam is a PhD candidate at the University of Mannheim. She carries out research on political behaviour with a focus on identity politics and a regional interest in Europe and India.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.