Press freedom is necessary to advance environmental protections across the globe

Journalists face increasing threats and obstacles to investigating environmental conditions internationally. In new research, Jeff Ollerton, Matt Walsh and Ted Sullivan find that press freedom goes hand in hand with a higher level of environmental protection. Therefore, for countries to address the climate crisis, they need an open, well-resourced media.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

Environmental protection is vital if countries are to conserve the natural capital and ecosystem services on which 21st-century societies depend, and is enshrined within the international treaties, policies and legislation that support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Progress towards these goals and others such as the IPCC’s targets for reduction in greenhouse gasses and IPBES’s reversal of landscape degradation, requires monitoring by governments, NGOs, and by civil society at large. A free and independent press is a vital part of this monitoring process if democracies are to hold governments and corporations to account, as investigative journalism has demonstrated in high-profile cases such as The Guardian newspaper’s exposé in 2009 of toxic waste dumping in Ivory Coast by the multinational company Trafigura. Journalists also have a role to play in promoting issues and campaigns, for example reduction in single-use plastic, pollinator conservation, wildlife crime, and climate change. In this regard, the relationship between NGOs and the press is vital. NGOs campaign on issues, but usually to niche audiences, whereas press coverage can elevate public concern over an issue, leading to pressure for political change. The EU’s moratorium on neonicotinoid pesticides is just one example of this process, as is the ban on CFCs following concerns about ozone layer depletion and restrictions on the use of DDT. More recently, the print media’s championing of climate activist Greta Thunberg and the organisation Extinction Rebellion demonstrates the way in which the press brings global environmental issues to the public’s attention.

We hypothesised that there is a causal link between press freedom and environmental protection, a relationship that has been examined regionally – see for example Wang’s (2005) study of the role of print media in the Pearl River Delta – but has never previously been evaluated at an international level. We tested this relationship using two robust, global, country-level measures: the World Press Freedom Index (WPI) by Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF; 2018) and the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), developed jointly by Yale University, Columbia University, and the World Economic Forum.

The World Press Freedom Index uses an expert questionnaire plus data on abuse and violence towards journalists in each country. Global in approach, it brings together qualitative and quantitative data from 180 countries to produce an analysis of press freedom that reflects indicators such as government pressure, self-censorship, and levels of violence towards journalists. The Environmental Performance Index includes twenty indicators that cover all aspects of environmental health and ecosystem function and protection, including air and water quality, pollution, protection of biodiversity, deforestation, the state of fisheries, greenhouse gas emissions, and sustainable agriculture. Both the WPI and the EPI are produced annually by their respective organisations.

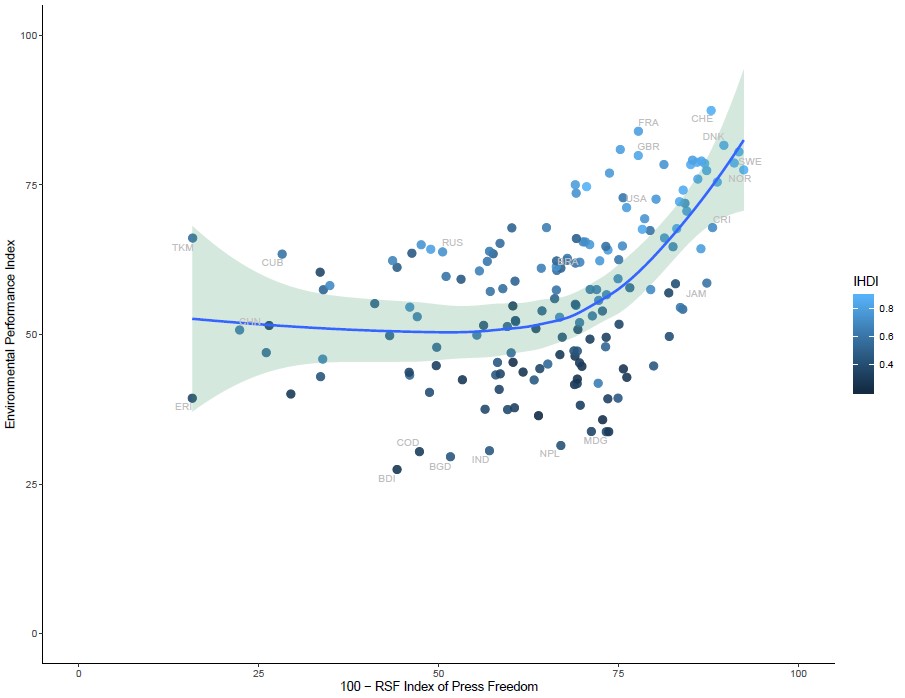

As predicted there is a significant relationship between the degree of press freedom in a country and the level of environmental performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The relationship between the World Press Freedom Index (WPI) and the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) for 168 countries in 2017

Note: The WPI has been rescaled as 100-WPI. A LOESS regression has been fitted with a ribbon showing 99% confidence interval. LOESS cannot be used to calculate R2 but the closest approximation to this relationship, a two-order polynomial of the form y=0.0002x2-0.0165x+0.849, gives an R2=0.26. The UNDP’s Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) has been assigned to each country. In the few cases where a country’s IHDI has not been calculated, the average for the region in which that country is situated has been used.

Countries that suppress media activities and abuse their journalists tend to score low on the EPI, and thus the protection they give to the natural environment and to the health of a populace. Conversely, countries with a culture of press freedom also tend to do well in terms of environmental performance, protecting both ecosystems and human populations. This relationship between press freedom and environmental performance is non-linear: below a critical point environmental performance is low regardless of the level of press freedom. Above that point, environmental performance rapidly increases as a function of press freedom.

It is possible for countries to have a relatively restrictive press yet have a mid-ranking environmental performance; in Figure 1, Turkmenistan, Cuba and Russia are examples of this. Conversely some countries have a high degree of press freedom yet a poor environmental performance, for example Nepal, Madagascar and India. However, no country has both a highly restricted press and good environmental performance: a free press is a prerequisite for a country to protect its environment and peoples.

Although the pattern is clear from the data, and we would argue for an indirect causal link between the two, clearly there is a large amount of variation in a country’s environmental performance that is not explained by press freedom. Many drivers affect the ability or desire of governments and large corporations to protect the environment, including affluence, level of education, warfare, public awareness, NGOs, legal frameworks and their enforcement, corruption, and corporate social responsibility of businesses. Some of these are clearly influenced by the ability of journalists to investigate and report on failures of environmental protection, but others are beyond the normal influence of the press. The UNDP’s Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) captures some of these variables by combining measures of human health and longevity, education, and standard of living and has been mapped onto each country in Figure 1. Those countries with a higher IHDI tend to enjoy better environmental conditions and have greater press freedom, but that is by no means inevitable and exceptions exist across the range of IHDI values. One other important source of variation is that journalism differs in its nature even between countries with a high degree of press freedom. If the content that is being published is effectively ‘churnalism’ (Davies 2008), because the news organisations lack the resources to deliver investigative reporting, then one might expect a poor relationship between what appears to be a free press and environmental protection.

Countries for which an assessment has been made of press freedom but for which environmental data are not available are a source of concern. For example, Syria (WPI=81.49) and North Korea (WPI=84.98, the highest value of any country) both lack EPI evaluations due to those countries’ particular circumstances. We would predict that the environments in which the populations of those countries exist will be poor indeed, and this is backed up by local reports.

We estimate that just over one quarter of the variation in the EPI of countries is explained by press freedom. That such a compelling signal of the role of journalists comes through the data is indicative of the value of having a strong and independent press. It is therefore worrying that press freedoms are being increasingly restricted in many countries. This was highlighted in a recent RSF report (Reporters Sans Frontières 2016) but the situation is, if anything, getting worse: there have been more recent accounts of journalists being excluded from briefings by government environmental bodies in the USA and beaten up while investigating allegations of pollution in China. Indeed it is estimated that 40 journalists were murdered because of their coverage of environmental issues between 2005 and 2016. This should concern all journalists and the public: restrictions on press freedom within a country have the potential to result in a deterioration in the health of both people and the ecosystems on which they depend.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position Democratic Audit.

About the authors

Jeff Ollerton is Professor of Biodiversity at the University of Northampton in the UK, with an international profile in the field of biodiversity, focused particularly on understanding and conserving plant-pollinator interactions, advising governments, media, and charities, and lectures and writes for the general public as well as his peers. His work has been published in Nature, Science, Ecology, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, and Ecology Letters. He has long been fascinated by the relationship between people and the environment, and is currently completing a book entitled Pollinators and Pollination: nature and society, which is due for publication in spring 2020.

Matt Walsh is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Before moving into academia in 2014, he was a working journalist for twenty years, mainly in broadcast and digital media. He was deputy editor of the ITV News Channel, producing and editing ITV News programmes covering the 9/11 attacks, the Iraq war and the 7/7 suicide bombings, as well as producing ITV’s coverage of the 2004 American presidential election. In 2006 he moved to The Times & Sunday Times as head of multimedia and launched several podcast and digital video series. In 2008, he returned to ITN as an executive producer developing new services for the broadcaster.

Ted Sullivan is a Senior Lecturer in Journalism recently retired from the University of Northampton, specialising in media law and public administration. In a 40-year career he has worked as a journalist, PR practitioner and educator in Canada, Asia and the UK, contributing to outlets such as the BBC, CBC, the Wall Street Journal and the South China Morning Post. For the past two years he has been working on media research projects on behalf of Reporters Sans Frontieres, the Paris-based press freedom NGO.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.