Is the resurgence of Europe’s far-right a cultural or an economic phenomenon?

There has been a spectacular rise in support for far-right parties in Europe over the last two decades, but what has driven this electoral success? Drawing on new research, Vasiliki Georgiadou, Lamprini Rori and Costas Roumanias demonstrate that different types of far-right party have benefitted from different factors: economic insecurity has helped increase support for ‘extremist right’ parties, while cultural factors have been associated with the growth of the ‘populist radical right’.

Photo by slon_dot_pics from Pexels

In a recent study, we find robust evidence that both economic insecurity and social backlashes are associated with rises in the vote shares for far-right parties in Europe. We distinguish between two different groups of parties, those that are part of the ‘extremist right’ (ER) and those that are part of the ‘populist radical right’ (PRR). Support for the extremist right is mostly associated with economic insecurity, while support for the populist radical right is associated with a cultural backlash.

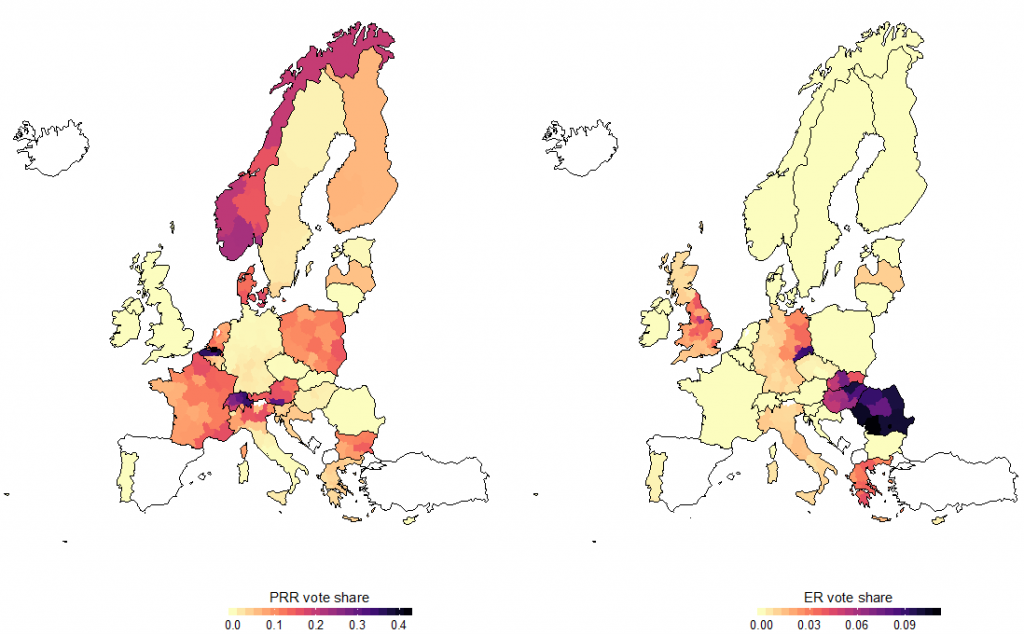

Figure 1: Average vote share for far-right parties in Europe (2000–13)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Electoral Studies.

By and large, theoretical accounts of voters’ support for far-right parties focus on economic and cultural insecurities. Economic insecurities turn voters of lower and more vulnerable social strata towards paternalistic far-right parties. Social backlashes associated with cultural insecurities are caused both by rapid social and demographic changes in post-modern economies and by value changes reacting to multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism. So far support for these theories has been mixed, with studies identifying both positive and negative effects.

We focused on two key premises to explore the correlates of European far-right politics. First, we noted the heterogeneity of far-right parties, accounting for differences in extremism and anti-system stances between the more moderate populist radical right parties and the more reactionary extremist right parties.

Second, we recognised the potential importance of regional effects for the way constituencies vote. Covering 28 countries, 1,170 first and second order elections and using data from 266 European NUTS 2 level regions, our analysis provides a pan-European comparison at the finest level for which a large number of diverse socio-economic controls were available.

We tested for the possible effects of indices of economic insecurity (unemployment, tax rates, growth) and cultural backlash (various indices of immigration). In the case of unemployment, we found a significant and systematic relationship between unemployment vote shares for populist radical right and extremist right parties in both national and European elections throughout Europe. With respect to other economic indices, we found that both the populist radical right and extremist right vote shares fell with rising GDP, but differed to each other with respect to growth: support for populist radical right parties was unresponsive to growth, whereas the extremist right vote share fell in economically booming regions.

Although there is evidence of a positive relationship between immigration and the far-right vote, the connection was both more pronounced and more robust for populist radical right parties. The effect of immigration on the extremist right was less strong and did not have statistical significance in some cases.

Do economic and cultural insecurities reinforce each other?

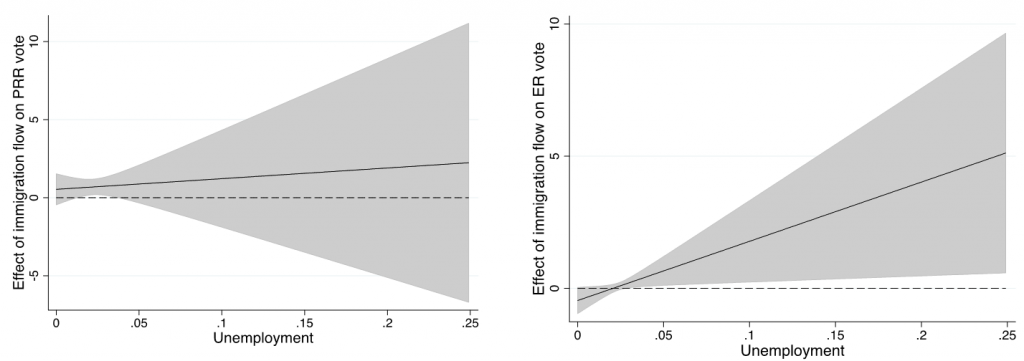

In the case of extremist right parties, we found significant interaction effects between unemployment and immigration. For populist radical right parties, the effect was positive but not statistically significant. Figure 2 captures the interplay between unemployment and immigration for the two types of far-right party considered in our analysis. In the case of populist radical right parties, immigration has a direct effect on electoral shares. For extremist right parties, the effect of immigration is mediated (amplified) through the feelings of economic insecurity experienced in periods of high unemployment.

Figure 2: Partial effects of unemployment and immigration

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Electoral Studies.

Increasing inequality had a positive and significant impact for populist radical right support, but a negative and significant impact for extremist right parties. Aside from populist radical right parties being rewarded for their anti-elite stances, growing inequality offers such parties an opportunity to also denounce the perceived drivers of inequality, such as globalisation.

Extremist right parties on the other hand are typically anti-system parties. One possible explanation for the negative relationship between inequality and support for these parties is that the ‘winners’ from growing inequality are likely to shy away from backing complete systemic change. Meanwhile those who lose from inequality have little incentive to back extremist right parties as they often recognise inequalities as ‘natural’, in contrast to populist radical right parties.

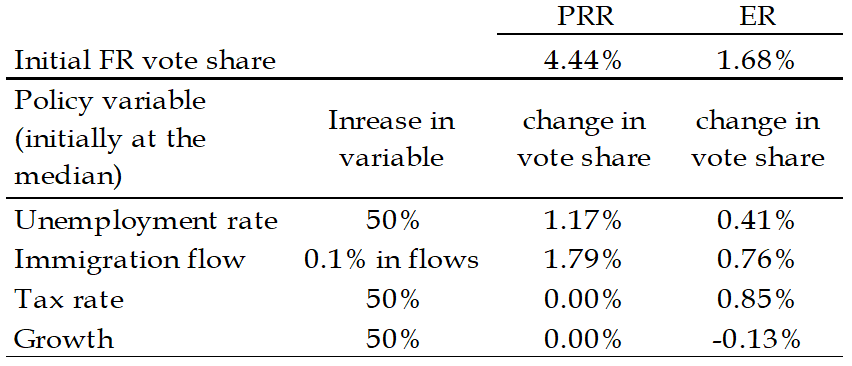

Table: Effects of key variables on far-right vote share

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Electoral Studies.

How do our findings relate to potential shocks in the economy and abrupt shifts in the cultural synthesis of the population? The table above reports the effects on the far-right vote of a 50% increase in the median of a number of key explanatory policy variables. Other things being equal, unemployment has a similar effect on both the populist radical right and extremist right: a 50% rise in median regional unemployment contributes to a 1.17% and 0.41% increase in PRR and ER electoral shares respectively.

A 0.1% rise in immigration flows (from 0 to 0.1%) will increase the populist radical right vote by 1.79% and will cause a rise of 0.76% in extremist right vote shares. A 50% rise in the effective tax rate from 10% to 15%, will leave the populist radical right vote unaffected but will cause a 0.85% rise in the extremist right vote share. Finally, a 50% rise in median growth rates will not affect the populist radical right vote but will reduce the extremist right vote share by 0.13%.

Our analysis suggests that in order to slow down or even reverse the ascending course of the European far-right, policy measures adopted might need to be tailored to the specific characteristics of the parties in each country. Regions that have witnessed a surge by populist radical right parties should focus mostly on reducing current social backlashes and inequalities, whereas in regions with strong extremist right parties, it might pay to focus more on reducing economic insecurity caused by a slowing economy and rising unemployment.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Electoral Studies.

This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog.

About the authors

Vasiliki Georgiadou is an Associate Professor at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences in Athens and Director of the Centre For Political Research. Her current research interests focus on comparative analysis of far right parties, populism, radicalism and violent extremism.

Lamprini Rori is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Exeter. Her research projects focus on the far right in Europe, political violence, the role of emotions in radicalisation and the dynamics of political networks in social media. She is currently Principal Researcher of the LSE Project “Low-intensity violence in crisis-ridden Greece: evidence from the radical right and the radical left” and the Early Career Fellow of the British School at Athens.

Costas Roumanias is an Assistant Professor at Athens University of Economic and Business. His research interests include formal voting models, empirics of elections, radical voting, comparative politics and behavioural economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.