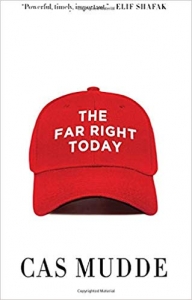

Book Review | The Far Right Today by Cas Mudde

In The Far Right Today, Cas Mudde provides readers with a comprehensive overview of contemporary far right politics: a pressing task considering that groups or parties once located on the fringe of mainstream politics have experienced a surge in popularity over recent years across Europe and beyond. The most worrying aspect of this surge, argues the author, is the mainstreaming and normalisation of the far right. This is an excellent, accessible and timely book that effectively challenges conventional thinking on the topic, writes Katherine Williams.

Picture: Johnny Silvercloud/(CC BY SA 2.0) licence

The Far Right Today. Cas Mudde. Polity. 2019.

In The Far Right Today, Cas Mudde gives an accessible account of the history and ideology of the far right as we know it today, as well as the causes and consequences of its mobilisation. Its ultimate aim is to equip readers with the tools needed to critically engage with the challenges the far right poses to liberal democracies across the world and enable them to effectively counter these threats.

The book is comprised of ten principal chapters, with topics running the gamut from history and ideology, to people and gender. The author also provides readers with four in-depth vignettes, a chronology of events, a glossary of key terms and recommendations for further reading. These extras will no doubt prove invaluable to those who wish to broaden their understanding of the contemporary far right: a time period referred to as the ‘fourth wave’ by Mudde throughout discussion.

While the book itself is designed primarily with non-academic readers in mind, they too must grapple with one of the more perplexing aspects of this debate: terminology. As frustrating as this can be, it remains an essential task. As scholars in the field well know, there is no consensus between academics when it comes to terminology, but most agree that the ‘far right’ is an umbrella term that encompasses the broader subgroups of the radical right and extreme right. In a nutshell, the differences between the two concern their attitude to democracy: the former operates within democratic institutions, and the latter, quite simply, does not. Mudde provides readers with a series of examples that contextualise these distinctions, and touches upon another term that has found a foothold in contemporary political debate: populism.

Mudde describes populism as a ‘thin’ ideology that views society as being split into two groups, the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’, and that politics should reflect the will of the people, or the volonté générale. In theory, populism is pro-democracy, albeit against liberal democracy. While the debates surrounding terminology may be viewed as an academic exercise, it is important for readers to understand these distinctions, particularly as they can vary on a country-to-country basis, as is the case with Germany where far right groups can face monitoring by the intelligence services if they are considered too extreme.

Commentators have struggled to pinpoint the reasons behind the recent success of the far right, and many theories have resurfaced following the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2016. Given the contentious nature of far right politics, this is hardly surprising, but, as Mudde wryly observes, following the breakthrough of a new far right party in one country or another, many academic and media commentators attempt to reinvent the wheel. There is, in fact, a wealth of existing scholarship on the topic. With this in mind, the author unpacks four of the most prominent debates in the ‘Causes’ chapter: protest versus support; economic anxiety versus cultural backlash; global versus local; and leader versus organisation. Do supporters of the far right express support against mainstream parties or support for the far right with their vote? Do individuals vote for the far right because of economic or cultural reasons? Is this support strictly local or is it more to do with globalisation and modernisation? What does the far right offer supporters?

The idea that the electorate are responding to economic concerns when they vote for the far right is a prominent one – the author himself asserted back in his seminal 2007 work Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe that ‘it’s not the economy, stupid!’ – but nonetheless, there are no simple answers. As Mudde notes, these debates are not easy to disentangle from one another as they invariably share many similarities, as discussed extensively throughout this section. The chapter also touches upon the role of the media in disseminating and thus mainstreaming the ideological agenda of the far right: prominent examples being the near-constant championing of Trump by Fox News, as well as the support of the Daily Express for UKIP when the party were at the height of their success. The author also discusses the role that social media platforms play in allowing individuals or groups to circumvent ‘traditional gatekeepers’, thus enabling them to position themselves at the forefront of political debate: a noteworthy example of this would be Breitbart News in the US.

Like most political entities, the far right is extremely gendered, with many groups holding traditional views on the role of women in society. Some openly promote women’s rights but their claims that gender equality has already been achieved betray an underlying conservatism. The author makes an interesting distinction between the ‘benevolent’ sexism inherent in the far right (i.e. the view that mothers and the traditional family unit are the foundation of the nation), and the ‘hostile’ sexism that can be encountered online. In the ‘Gender’ chapter, the author discusses the so-called ‘alt right’ and online ‘Manosphere’, thoughtfully illustrating the different manifestations of the far right as well as demonstrating the ‘real-world’ consequences of online mobilisation. In forums, young men (some of whom characterise themselves as ‘incels’, or ‘involuntarily celibate’) discuss their hatred of women (‘Stacys’ or ‘Beckys’), feminism, themselves and other men (‘Chads’). Some revel in graphic fantasies of enacting violence against women in response to women’s alleged lack of sexual interest in them. Consequently, women have been the primary target of self-described incels who have taken their fantasies offline and committed heinous crimes in retaliation to these perceived slights.

The chapter discusses prominent women who may already be familiar to readers, such as politicians like Marine Le Pen (Rassemblement national) or Alice Weidel (Alternative für Deutschland), but crucially it extends its analysis to note the ways in which so-called ‘alt-right’ personalities such as Lana Lokteff (from TV station Red Ice) or Lauren Southern (formerly of Rebel Media) consolidate the production, maintenance and reproduction of white supremacy – and indeed, male supremacy – through their various social media platforms. Invariably, there are many contradictions inherent in this particular brand of anti-feminist activism, particularly as some women do not live the type of lifestyle they doggedly advocate for other women, like having a lot of children in efforts to ‘secure’ their future.

As Mudde points out, men are often overrepresented in the academic literature on the topic of the far right more broadly, but there is evidently an urgent need to further address issues such as masculinity and the elements which underpin ‘male supremacy’. Either way, it becomes clear that responses to the far right would benefit from the inclusion of a gender perspective in order for academic and media commentators alike to effectively assess how gender is instrumentalised in the far right, and what challenges this may pose to counter-extremism efforts.

Throughout the course of his career, Cas Mudde has been instrumental in shaping scholars’ understandings of the far right, and The Far Right Today is an excellent and accessible primer for those new to the topic and a helpful refresher to those already familiar with its debates. Given the normalisation and mainstreaming of the far right online, in the news and increasingly within our political institutions, it becomes incumbent upon readers to educate themselves in order to counter the real threat the far right poses to liberal democracies across the world.

This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on the LSE Review of Books blog.

Katherine Williams is an ESRC-funded PhD candidate at Cardiff University. Her research interests include the role of women in far-right groups, feminist methodologies and political theory and gender in IR. You can follow her on Twitter: @phdkat.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.