General election 2019: a different contest in Scotland

Ahead of the Westminster election on 12 December, James Mitchell explains how party competition in Scotland is shaped by interrelated questions of policy, competence, independence and Brexit, which for short-term tactical reasons places the Tories and SNP in direct competition, and squeezes Labour and the Lib Dems, while most likely leaving longer term issues unchanged until after the Scottish parliamentary elections of 2021.

Scottish Independence protest, 2019. Photo by Adam Wilson on Unsplash

‘And over to Scotland where a different election is being fought….’ This has been the refrain for many elections now. But the extent to which Scottish elections are different is exaggerated just as the extent of uniformity was in the past. Even in the supposedly halcyon days of British electoral uniformity there was always a distinct Scottish dimension.

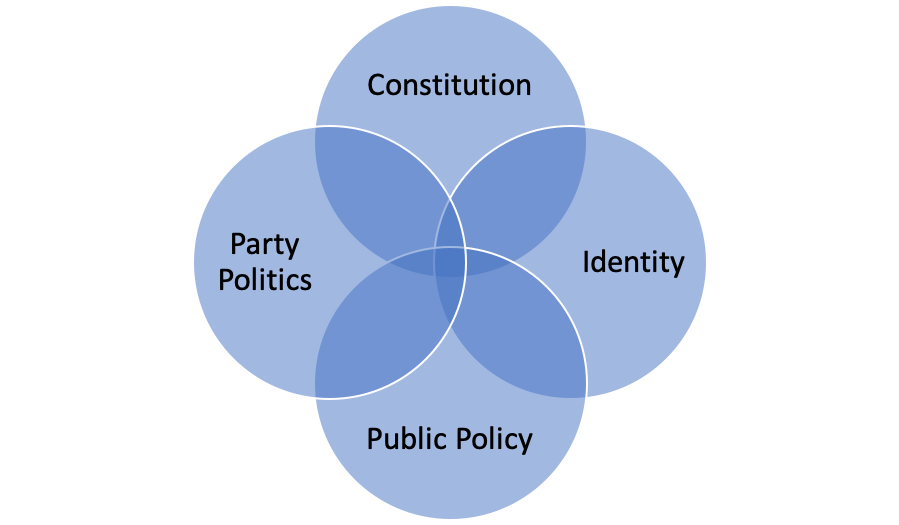

The main difference is the Scottish Question, often mistakenly assumed to be a single constitutional question informed by national identity. The Scottish Question is more complex; it is a series of related questions and many are no different from those facing voters across the UK and beyond. It is their inter-relationship that makes the distinct Scottish Question.

The SNP came to be the largest Scottish party because it was perceived as competent. Supporting Scottish independence contributed to its image as the party most willing to stand up for Scottish interests but in the past independence held it back as much as it has assisted it electorally. Today, with the electorate split down the middle on independence, the issue is an unambiguous asset in a multi-party system in which the SNP has no serious competitor for the independence vote. As its opponents fight amongst themselves for the title as most anti-independence party, the SNP glides unhindered on a sea of independence voters. The Scottish Greens support independence but remain a fringe party, able to pick up enough regional list votes to give it seats in the Scottish Parliament but not enough to win constituencies in Holyrood or the Commons. The Greens look like an earlier version of the SNP – an idealistic, oppositional amateur activist party.

The Scottish Question

What took support for independence to 45% in the 2014 referendum was the combination of national identity, party politics and policy preferences. Instrumental reasons played a significant part in the result and are likely to be the determining factor in any future referendum. For many voters the key focus is on good government, public services and the economy but seen through the prism of which constitutional order would deliver best outcomes.

In many respects, the SNP is a version of what Labour once was – respectable, cautious and hostile to the Conservatives. The SNP and Labour are like rival siblings, with all the intensity of family feuds though aghast at any suggestion they are related. The shift of Labour voters to the SNP involved the replacement of an old tired model with a shiny new one rather than a mass conversion.

Scottish electoral politics is often defined by what parties oppose. The Conservatives have long been Scotland’s political Aunt Sally, an easy target with opponents competing to be most hostile. Labour’s past strength lay in its anti-Tory position. Devolution provided the SNP with the opportunity to challenge Labour as Scotland’s most effective anti-Tory party.

The dynamics have changed. The SNP became the Aunt Sally when it rose to prominence and provided the Tories with an opportunity in outbidding Labour and the Lib Dems as most hostile to the SNP and independence. The constitution also allows the Scottish Tories to avoid having to defend their government’s record at Westminster. The Tories need the SNP and the threat of independence to retain existing levels of support.

Many erstwhile Labour voters moved to the SNP, having voted for independence in the 2014 referendum. Labour has struggled to win these voters back while maintaining strong opposition to independence. By focusing almost exclusively on independence, even all but abandoning the Conservative label, the Tories won over some Labour voters. SNP seek to win Labour voters by portraying themselves as anti-Conservative while the Tories seek Labour voters by portraying themselves as anti-SNP.

Brexit added a dimension in 2017. Leaders of all parties in Holyrood campaigned for Remain which 62% voted for in Scotland. But there was a significant element of the Scottish Conservative Party that supported Leave. With no other major party in Scotland claiming to represent the Leave minority, the Tories were able to combine a strong anti-independence message while harnessing the minority Leave vote. This appears to be their strategy in this election again.

A significant anti-SNP vote will remain so long as the SNP is in power in Holyrood and continues to demand a second independence referendum. Both the SNP and Tories know that there is little, if any, prospect of an independence referendum this side of the next Holyrood elections in 2021 but each maintains the fiction of a 2020 independence referendum to shore up its own support. Labour suffers the same fate familiar to the Liberal Democrats of being caught in the middle in an adversarial polarised battle, and will continue to struggle so long as independence and Brexit dominate Scottish politics.

The Liberal Democrats had high hopes at the start of the campaign in Scotland with a Scottish MP as leader and a clear position on Brexit, but Jo Swinson struggles with that classic problem of whether her party leans more to the left or right. Paddy Ashdown abandoned Lib Dem ‘equi-distance’ and leaned left. Jo Swinson leans to the right which makes it more difficult to win disaffected Labour votes. The Liberal Democrats struggle with a leader distracted by her inability to distance herself from her part in the Tory–Lib Dem coalition and who needs Tory voters to hold her East Dunbartonshire seat.

The SNP sees Brexit through a short-term tactical lens. The Brexit referendum highlights divergence of opinion north and south of the border to its advantage. It seeks to frighten voters at the prospect of Boris Johnson and a hard Brexit. But the SNP is almost silent on the implications of a hard border between the rest of the UK outside the EU and an independent Scotland in the EU. Greater focus on opposing Brexit while parking an independence referendum until a more realistic time after the next Holyrood elections would make voting SNP more palatable to many pro-Remain independence sceptics.

The results of the election will make Scotland look very different from the rest of the UK but that appearance hides a more important reality. What happens in Scotland in this general election is unlikely to have a major impact on the outcome or developments over independence before the next Holyrood elections.

This article gives the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

James Mitchell holds chair in public policy, Edinburgh University. His books include Hamilton 1967, Luath Press, 2017; with Rob Johns, Takeover: explaining the extraordinary rise of the Scottish National Party, London, Biteback Publishing, 2016, and The Scottish Question, Oxford University Press, 2014. He co-directs the SNP/Scottish Green Party ESRC study ‘Recruited by referendum’, RG13385-10. He tweets @ProfJMitchell.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Indeed, the triple mandate for a second referendum we already hold has been ignored for several years now. I strongly suspect that even if the SNP take every single seat in Scotland it will be ignored in terms of letting us have a Section 30.

Though there are other methods we could employ. Constitutional lawyers say it is still arguable whether or not the original Section 30 order in the Edinburgh agreement is still in force. So the SNP could take that to court and should have done when the Maybot first said ‘now is not the time’.