Female parliamentarians still face a motherhood penalty, but the evidence globally suggests it can be ended

It has long been assumed that female politicians face a trade-off between having a family life and a successful parliamentary career, while their male colleagues do not. Devin Joshi and Ryan Goehrung find that, while female MPs are still more likely to be unmarried and have fewer children, the gap in parental and marital status of members of parliament varies considerably internationally. They argue that by implementing social reforms to reduce gender inequality, and introducing specific reforms to create more inclusive parliaments, this gap could be closed worldwide.

Italian MEP Licia Ronzulli. Few parliaments worldwide accommodate mothers in the same way. Picture: European Parliament/ (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Why do we still rarely see mothers, especially those with young children, represented in parliament? The rarity of scenes like the one above of women successfully balancing motherhood with a career in politics underscores an observable fact that relatively few members of parliament (MPs) are women with young children. A commonly held belief in many societies is that women who would like to serve in politics, especially those with young children, are heavily disadvantaged. Campaign funders, media elites and political party gatekeepers may inhibit the promotion and selection of female candidates with small children because they fear such candidates will lose votes among the electorate. By contrast, these same gatekeepers promote children as assets for male MPs, whose campaigns typically benefit from emphasising their fatherhood. So, what’s going on?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a lot of this dynamic has to do with gender role expectations. The basic underlying problem seems to be a perceived care conflict along gendered lines. Many believe that given limited time and resources, a female MP must necessarily choose between either a) caring for her own children/family members, or b) caring for her electoral constituents and/or society as a whole. By contrast, male MPs are rarely seen as facing this conflict because they are assumed to outsource care work to others. Mothers with young children also face much higher levels of scrutiny because of the busy schedules of MPs on top of gendered social expectations that mothers do most of the parenting and care work themselves.

Recent studies, however, suggest that some changes are underway. Experimental surveys have found prospective voters to prefer women candidates who are mothers and who are married over women who deviate from conventional gender role expectations. There also appears to be increasing confidence among voters that mothers in politics can juggle the demands of parliament with parenting. Studies of the media likewise observe a growing ‘normalisation’ of women in politics, whereby women now are less likely to be seen as outsiders or intruders in parliament compared to several decades ago.

Multi-country results indicate a gender gap persists

Previous research has often found that women who followed traditional gender expectations of getting married and having children were less likely to enter parliaments than their male counterparts. We conducted a study to see if this is still the case, building on earlier research on parliamentary websites and transparency. We obtained marital and child status information on MPs from all countries that post such background information on their parliamentary websites. This allowed us to examine family patterns of more than 4,000 MPs in 25 countries from diverse regions around the world.

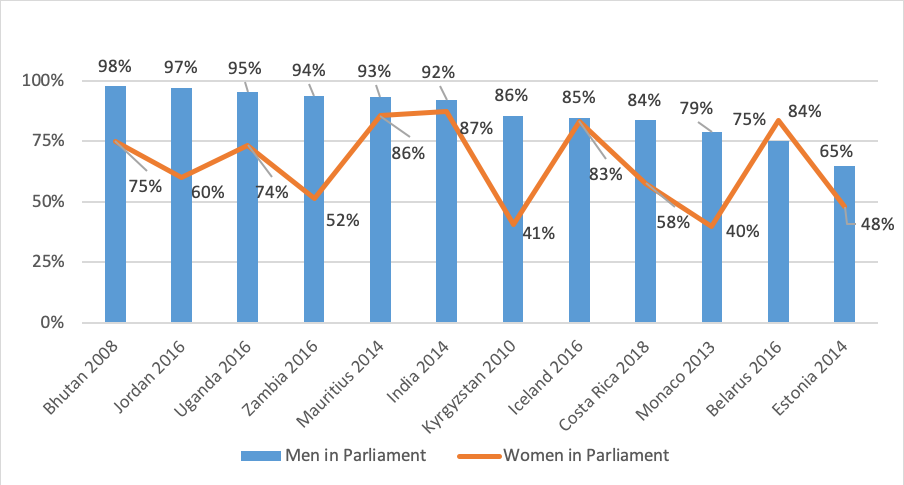

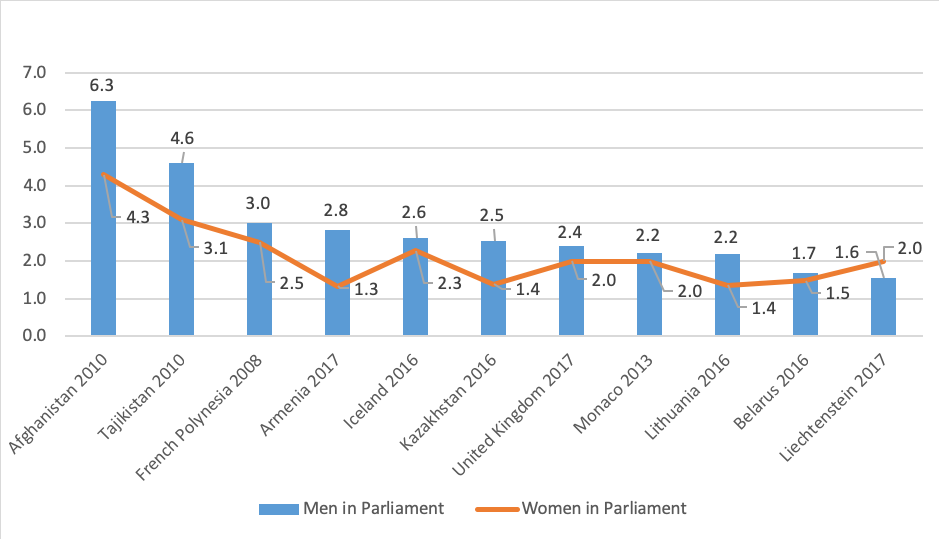

When we added up the numbers, we found women MPs were indeed still more likely to be un-married, childless, or to have fewer children than their male counterparts. Interestingly, these ‘family gaps’ were not uniform across national contexts and were most pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, especially those with higher child mortality rates. When it comes to marriage, we found a significant gap between women MPs and men MPs (selected examples are shown in Figure 1 below). As for children, we also found similar results. In almost all countries, women MPs had fewer children than men MPs as shown in Figure 2. However, there were some countries that bucked this trend. For instance, Iceland featured no statistically significant child gap or marital gap between male and female parliamentarians. This tells us that it is definitely possible in some contexts to eliminate such gaps. In our comparative research, we found smaller family gaps between men and women tended to correspond with increased share of women in paid employment, more comprehensive social welfare provisions, and greater presence of women in parliamentary leadership positions.

Figure 1: Percentage of MPs who are married when elected by gender (2008–18)

Figure 2: MPs’ average number of children by gender (2008–17)

Recommendations for reform

These findings point to the importance of public policies, parliamentary rules, and critical actors in reducing time-demands on parents who are MPs. Aside from the broader structural inequity of women being expected to take primary responsibility within the household for raising children and taking care of many household tasks, the institutional design of parliaments can also disadvantage mothers. One way of addressing this is to create more ‘gender-sensitive parliaments’ and ‘diversity-sensitive parliaments’ that are responsive to both women’s and men’s needs to balance work with family responsibilities.

Recommendations include having easily available on-site breast-feeding and childcare accommodations and facilities, legally guaranteed paternity and maternity leaves, full-time substitutes and proxy votes for MPs who need to take leave, which was only introduced in the UK House of Commons in 2019, and flexible work-time arrangements that can also serve as a model for other workplaces in society. The roles of partners (and extended families) in taking on parental and household responsibilities and supporting women’s careers is also crucial as are state benefits and programmes supporting all mothers in society such as parental leaves and publicly subsidised childcare.

How do we get there from here? First, at the societal level, the mobilisation of activists and changing gender role perceptions along with greater levels of women’s participation in the paid workforce, and a more developed welfare state can help to address supply side issues of women’s political representation by providing baseline conditions for more qualified women candidates. Second, as more women (and mothers) become political leaders in all branches of government, including parliament and its various committees, we should begin to see more impetus for change (for more on women’s political leadership see here). Third, by reforming parliamentary institutions and rules in ways that take care work into account rather than assuming such labour is handled by other members of MPs’ families we can reduce one of the longest-standing gendered barriers to representation in parliaments across the globe.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It is is based on the following research paper: Joshi, Devin K. and Ryan Goehrung, ‘Mothers and Fathers in Parliament: MP Parental Status and Family Gaps from a Global Perspective’, Parliamentary Affairs.

About the authors

Devin K Joshi is Associate Professor of Political Science at the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University.

Ryan Goehrung is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.