General election 2019: a postcode lottery

The 2019 general election produced a strong Conservative majority in the House of Commons, with the first-past-the-post electoral system delivering the party 56% of parliamentary seats on the basis of 43.6% of all votes. Beyond this national figure, Ian Simpson explains, the nations and regions of the UK returned some even more disproportional results, meaning millions of voters across the UK are left unrepresented in Parliament.

Picture: Alejandro Garay from Pixabay

Professor Patrick Dunleavy’s post-general election article for Democratic Audit revealed how last December’s poll saw a return to form: high levels of disproportionality typically associated with UK general elections held under the ‘first-past-the-post’ (FPTP) electoral system. Here, we will delve into the levels of disproportionality seen in the different nations and regions of the UK, to reveal how where you live and who you voted for affected the chances of your vote translating into representation.

As outlined in Professor Dunleavy’s article, a well-established tool for measuring the proportionality of elections is ‘deviation from proportionality’ (DV). The higher the DV score, the more disproportionate the election outcome. The Electoral Reform Society has calculated the overall DV score for the whole UK at the 2019 general election as 16.2, slightly lower than Professor Dunleavy’s figure, due to a small difference in methodology. However, the pattern is clear: 2019 marked a big increase in disproportionality – representation not matching how people have voted – compared to 2017. For comparison, Ireland’s recent general election, held in February 2020 under the proportional single transferrable vote (STV) system, saw a far lower DV score of 4.4, based on voters’ first preference ballots.

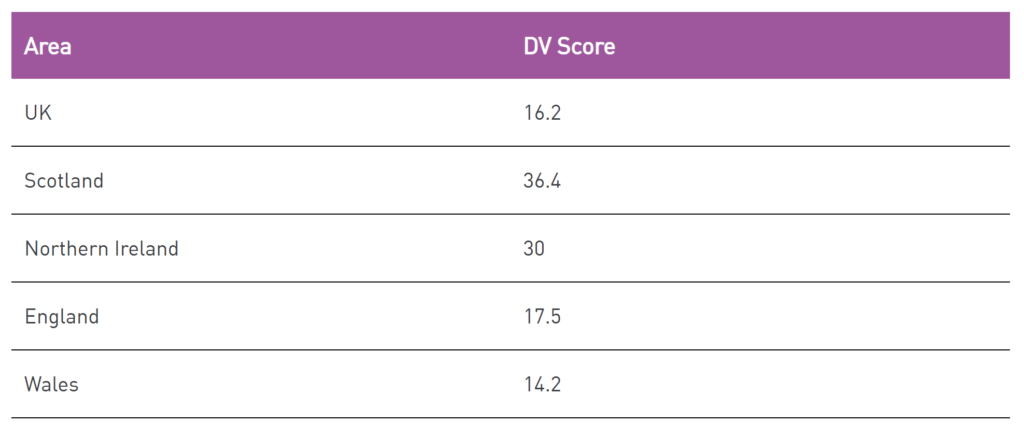

The overall DV score for the UK masks significant variations in disproportionality among the nations of the UK. Scotland (36.4) and Northern Ireland (30.0) have much higher DV scores than England (17.5) and Wales (14.2).

Figure 1: Deviation from proportionality (DV) score in the UK and in the nations

Source: Electoral Reform Society.

These results indicate that in Scotland over one-third of seats were ‘unearned’ in proportional terms, largely due to the SNP winning four-fifths of Scottish seats (81.4%), despite receiving fewer than half the votes across Scotland (45.0%). It should be noted that, despite benefiting significantly from FPTP, the SNP are in favour of moving to proportional representation (PR) for Westminster elections. Labour, who had traditionally benefitted from FPTP in Scotland (until 2015), were reduced to just one seat, despite receiving over half a million votes (18.6% of Scottish votes). A remarkable 95% of Labour voters in Scotland went unrepresented. Conservative voters were also underrepresented in Scotland: despite receiving one-quarter of votes (25.1%), the party picked up only 10.2% of seats. It required 115,489 votes to elect a Conservative MP in Scotland, compared with just 25,882 votes to elect an SNP MP.

Northern Ireland also saw a high level of disproportionality. Its multi-party politics are well-reflected in elections to the Northern Irish Assembly and local authorities, which are held under STV. However, in elections to Westminster its politics are forced into a warped two-party shape, with 83.3% of seats going to just two parties (DUP and Sinn Féin), despite nearly half (46.6%) of votes going to other parties. The Alliance Party won nearly 17% of votes but had only one MP elected, while the Ulster Unionist Party received nearly 12% of votes and failed to elect a single MP.

Although England has a lower DV score overall, some regions of the country have scores almost as high as Scotland’s. Southern and Eastern England, outside of London, have particularly high scores, largely due to the Conservative Party’s ability to hoover up seats to a degree that far outweighs its vote share. For example, in South West England, which has a DV score of 34.6, the Conservatives won 87.2% of seats, on 52.8% of votes. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Green Party received 45.4% of votes between them in the South West, yet managed to pick up only 12.6% of seats.

Figure 2: Deviation from proportionality (DV) score by English region

Source: Electoral Reform Society.

There is a very similar picture in South East England, which has a DV score of 34.1, where the Conservatives won 88.1% of seats on 54% of votes. Again, Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Green Party took a healthy vote share between them (44.2%) yet won only 11.9% of seats. The Liberal Democrats and Greens each won only one seat in the region, despite receiving nearly 850,000 and 200,000 votes respectively.

The East of England completes the hat trick of English regions with a DV score above thirty (with 32.6% of seats effectively ‘unearned’). Again, this was driven by the Conservatives outperforming their vote share, picking up 89.7% of seats on 57.2% of votes. Labour was particularly badly hit in this region, receiving nearly a quarter of votes (24.4%) but only 8.6% of seats, meaning it required nearly 150,000 Labour votes to elect an MP but only about 34,000 Conservative votes. The 2019 general election showed, once again, that Westminster’s voting system is short-changing both voters and parties, with different voters and parties hit hardest in different nations and regions.

Differences in disproportionality often stem from the difference in the rate of ‘decisive’ votes (i.e. votes that contributed to the election of the local MP) versus unrepresented votes (votes that went to non-winners) and surplus votes (votes above the amount the MP needed to secure representation), by party, as illustrated in Figure 3. Unlike a preferential system like STV, unrepresented and surplus votes under FPTP are effectively ignored, leading to huge variations in representation, depending on how ‘efficient’ – regionally concentrated, winning with small margins – a party’s vote base is.

Figure 3: Party breakdown of surplus and unrepresented votes

Source: Electoral Reform Society.

The contrast with Ireland’s recent election is stark. As one voter who has participated in general elections in both the UK and Ireland told the Electoral Reform Society: ‘In Ireland, your vote matters, no matter where you live. But first-past-the-post makes you feel your vote’s impact depends on your postcode. It is an issue of vibrancy compared to stagnation.’ Let’s choose the former and move to a proportional voting system, such as STV, for Westminster elections.

This represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. The article draws on a recent report by the Electoral Reform Society, ‘Voters Left Voiceless: The 2019 General Election‘.

About the author

Ian Simpson is a research officer for the Electoral Reform Society.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.