Covid-19 lockdowns: early evidence suggests political support and trust in democracy has increased

Making use of cross-country European survey data that was fielded both before and after Covid-19 lockdowns were implemented, André Blais, Damien Bol, Marco Giani and Peter Loewen find that support for the incumbent leader, support for government in general, and trust in democracy have all increased in the short term.

Photo by Manuel Peris Tirado on Unsplash

Governments around the globe have responded to the spread of Covid-19 by imposing strong confinement measures, following advice from a transnational expertise, though with some variations in timing and extent. These measures entail liberty-reducing and security-enhancing effects akin to special measures during terrorist crises, and have clearly prioritised the health of vulnerable individuals above generalised economic interests in ways that were ex ante not obvious.

There is little doubt that the current crisis has placed the state under the spotlight. It has highlighted a key question: when confronted with grave threats, do citizens trust the democratic system to respond? Yet the distinctive nature of the pandemic response yielded opposing guesswork among experts about likely public attitudes, resulting in two factions: those who believe that the lockdown boosted status-quo bias, and support for state action, and those who believe that it would sharpen the quest for change by increasing chaos and mistrust in authority.

In this paper, we take advantage of a representative cross-national survey focusing on key political attitudes in 15 Western European countries that was undertaken in March and April this year. Responses to the survey came both before and after the introduction of lockdown measures and so are able to capture the short-run dynamic of attitudinal change during the process of social confinement. The survey covers indicators of both specific political support – i.e. ones that relate to current political leaders or governments – and diffuse forms of political support, related to trust in an institution or a regime.

To identify the date at which the lockdown became operative we relied on the data gathered by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, which defined lockdown as nationwide and strictly enforced social confinements. Seven countries surveyed, including the UK, France, Italy and Spain, enforced such a lockdown over the survey period (to avoid data error, countries like Germany where the containment policy was decided at the subnational level were excluded). Because of the timing and method of the survey, some respondents were surveyed before their countries’ lockdown, and some after. Our main independent variable, therefore, is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the respondent was surveyed after their country’s lockdown enforcement date.

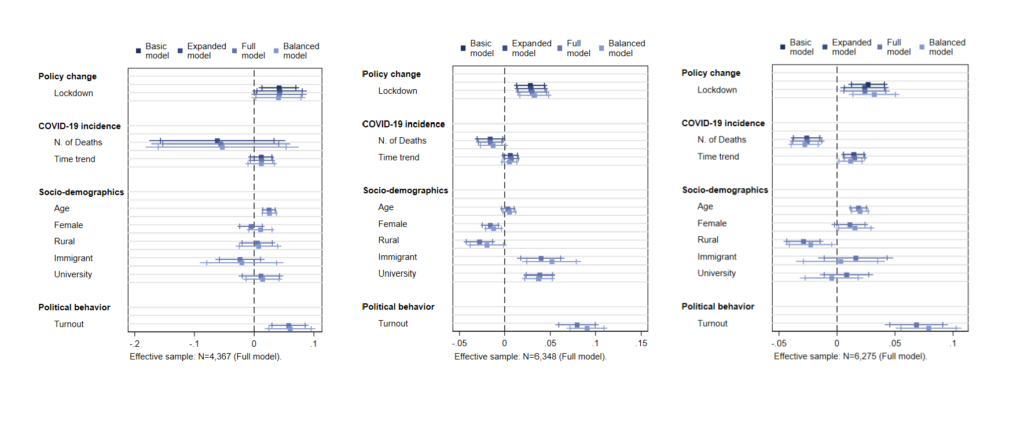

Figure 1: Effect of Covid-19 lockdown on support for incumbent PM’s party (a), satisfaction with democracy (b) and trust in government (c)

The graphs above plot the effect of lockdown enforcement on key political attitudes. The graph on the left shows that in countries where a lockdown was introduced during the survey period, voting intention for the party of the incumbent prime minister or president increased by 4%. The middle graph and the right graph show respectively that satisfaction with democracy and trust in government also increased by 2%. The results are net of incidence of Covid-19 in the country, as well as from the effects of a set of standard sociodemographic variables.

Several additional tests give us some confidence about the broad picture presented here. One problematic aspect would emerge if respondents surveyed before the lockdown were substantially different in terms of demographic features or social status from those surveyed after the lockdown. In that case, the reported increase in diffuse and specific support for democratic institutions may inaccurately reflect aggregate public opinion responses. However, luckily, we show that this was not an issue in our study. A second important test that we ran consists in isolating the effect of the lockdown from that of other milder policy restrictions. We find that the observed public opinion dynamic is unique to the lockdown, as schools and workplaces closing entailed no effect on political attitudes. Finally, we show that whereas the lockdown spurred support for existing political institutions, it had no effect on individuals’ self-position in the left-right ideological scale. This refines our overall picture, suggesting that the enforcement of the lockdown was not perceived as an ideological decision.

Taken together, our findings indicate that part of the population has become more supportive of its political leaders and democratic institutions since the pandemic lockdowns were implemented, resulting in a nonpartisan status-quo bias. It seems that people understand that strict social containment is necessary, and reward governments that decide to enforce it, at least in the short term. Furthermore, our findings suggest that it has a positive spill-over effect on support for democracy and its institutions.

This article is based on the authors’ working paper ‘The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy?’, which you can read here.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the authors

André Blais is Professor in the Department of Political Science and holds a Research Chair in Electoral Studies at the University of Montreal.

Damien Bol is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Economy, King’s College London.

Marco Giani is a Lecturer in Economics, King’s College London.

Peter Loewen is Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

“has a positive spill-over effect on support for democracy and its institutions.”

If you select such sample, then indeed you’d get such result. Had you picked Poland or Hungary, then, technically speaking, you should get a conclusion that it improved opinion of politician leaning towards illiberal democracies. In practices the predominant effect is the usual rallying round the flag, and it would be hard to filter out anything more.