Britain’s bloated payroll vote hampers Parliament in keeping a check on the executive

The latest Coalition reshuffle saw the size of the payroll vote remain steady, with 140 members of the Government benches in the House of Commons now compelled to vote in line with the frontbench, or else lose their position. In previous Democratic Audit reports and articles, Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone have considered the democratic implications of this convention.

The 2002 Democratic Audit report stated that: ‘[the] government usually commands a party majority in the Commons, swelled by an electoral system that gives it more seats than its votes justify; in most circumstances, government MPs support its policies, actions and legislation out of loyalty and self-interest’.

Developments since then suggest that while certain qualifications must be made, the basic premise that the government dominates the Commons – and through the Commons, parliament – has not been altered. Indeed, this position arises from the fundamental nature of the UK constitution as a parliamentary system with a fusion, rather than separation, of powers. To alter this arrangement would be a massive constitutional shift, raising various problems of its own. In its absence reforms to the legislature – though they have been, and arguably will continue to be, necessary – seem likely to yield only marginal, and possibly diminishing, returns.

Parliamentary business is largely determined by agreements between the respective whips. Among MPs of the governing party (or parties), the possibility of future appointments to ministerial posts acts to discipline those who sit on the backbenches; while ministers (drawn predominantly from the Commons) provide the government with a guaranteed bloc of support in parliament which stipulates that they must either vote with the government in divisions or resign.

The payroll vote comprises MPs who are part of the government and are bound by convention to vote with it in divisions, or resign. In its broadest definition, it includes government ministers and whips, as well as all MPs who are engaged as unpaid Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs) to ministers.

We regard the size of the payroll vote as a problem for two main reasons.

- A substantial payroll vote restricts the capacity of MPs to hold the government to account, which is one of the most important roles of the Commons.

- A very large payroll vote makes it very difficult for the Commons to amend proposed government legislation, even though growing numbers of backbench government MPs are prepared to defy the Whips.

It is difficult to see why the number of government posts continues to grow, particularly given devolution and the stated desire of successive UK administrations to move to ‘smaller government’. Concerns about the growth in the number of MPs making up the payroll vote are not new. Limits on the size of the payroll vote in the Commons were introduced in 1975, including specific limits on the numbers in each category (Cabinet Ministers, Ministers of State, Parliamentary Under-Secretaries of State, Whips). There is also legislation restricting the total number of Ministers and Whips in the Commons to 95. The most recent Government reshuffle which took place in October 2013 showed the size of payroll vote staying constant at 140, with the number of members of the House of Lords serving as Ministers has increased by three.

The gradual expansion in the payroll vote since the mid-1970s has been made possible by:

- Appointing a greater proportion of the maximum permitted among MPs (which has now been reached);

- Appointing more ministers from the Lords (now 26, up from 20 on 1979),

- Appointing additional unpaid Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs), for which there are no formal limits.

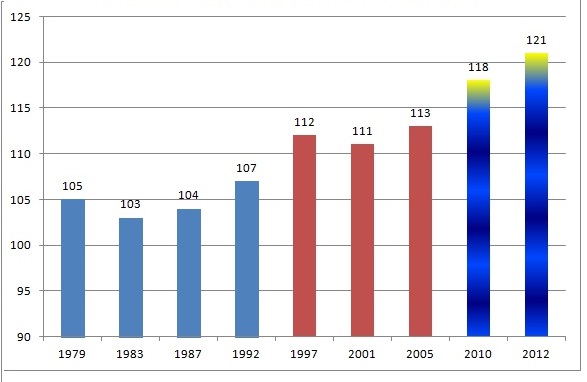

Fig 1. Total number of paid Government posts, 1979-2012

Source: Keith Parry and Richard Kelly, House of Commons Library

As the chart shows, there has been a very clear tendency for the total number of such roles to grow over time, particularly under the Labour governments of 1997-2010 and, even more clearly, since the formation of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010. The period since 1979 has also seen an overall increase in the number of unpaid PPSs, from 37 to 43, although the peak in the number of PPSs was 58 in 2001.

However, there are no signs that any government is willing to take the steps needed to reverse the trends highlighted above, such as placing a limit on the number of Peers who can serve as Ministers and also restricting the number of unpaid governmental roles.

Despite the growth of the payroll vote, there has been no corresponding evidence of an increase in independent behaviour by the backbenches. While the noted increase in rebellions by MPs on the government side might be said to provide a prima facie case for the increased independence of parliamentarians, the act of defying the whip does not in itself amount to meaningful independence – particularly in circumstances where it is highly unlikely to lead to a defeat for the government.

Indeed, increasing rebellions may partly be a symptom of poor communications between government and backbench MPs; or of ideological shifts within parties (for instance, resistance to New Labour from some Labour backbenchers, and Euroscepticism on the Conservative backbenches), rather than a sign of increasing autonomy on the part of the backbenchers.

Note: This blog was based on extracts from “The independence of parliament from the executive”, Section 2.4.1, of the 2012 Democratic Audit report. Please read our comments policy before posting. Shortened URL for this post: https://buff.ly/1a7zxGc

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report. Additional research about the 2013 Government reshuffle was incorporated by Sean Kippin.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.