Want a 50% turnout in a local election? Try Neighbourhood Planning

The government has introduced powers for local councils and community organisations to put new neighbourhood plans to a referendum of local voters. Chris Game has studied the referendums that have been held so far, and finds encouraging evidence of public engagement with the process.

A recent trickle of neighbourhood planning referendums might turn into a flood. Credit: Thomas Nugent (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Turnouts of over 50% in local elections, unless they coincide with parliamentary elections, are rare these days. I was quite excited, therefore, flicking through my new Local Elections Handbook, to see that the average turnout in this May’s Welsh unitary council elections was a heady 50.6%. But then I realised that 2012, not 2013, was Welsh unitary election year and that the 50.6% referred only to the postponed elections in the single authority of Ynys Mon (Isle of Anglesey).

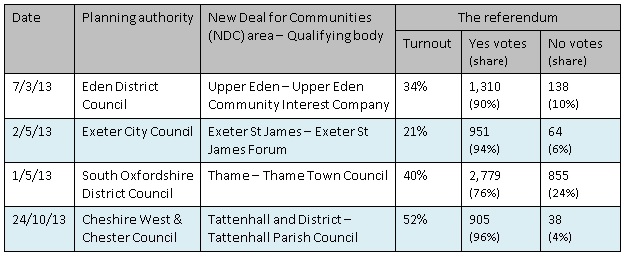

Don’t misunderstand. 50.6% is noteworthy by any GB local election standards, and it further confirms the Welsh reputation as our keenest voters – as does their 39% average turnout last year, compared with the sub-31% in this year’s English County elections. It may be, though, that the Government has discovered an alternative way of getting more of us interested enough to cast votes about something local governmenty. For on Thursday October 24th, in the Cheshire village of Tattenhall, there was another over-50% voter turnout in a local election – not for a mayor, councillor, or even police commissioner, but to express overwhelming backing for their neighbourhood development plan.

Introduced in the 2011 Localism Act, neighbourhood planning is about people having more influence over planning decisions affecting their daily lives: choosing where new homes, shops and offices should be built (or not built), what these buildings should look like, and what infrastructure is needed. The Act allows parish and town councils or other representative community groups to formulate Neighbourhood Development Plans (NDPs), that will shape development in their area – provided they conform with national policies and local planning strategy.

Proposed NDPs must pass an independent check, usually by a planning inspector, and are then put to a referendum, organised by the local planning authority. If the Plan receives majority approval, the planning authority must adopt it, and it becomes part of the legal framework with which future planning decisions must comply. So, with nearly 52% of residents having turned out in the fourth of these referendums, and 96% of them supporting the Tattenhall and District NDP, Cheshire West and Chester unitary planning authority now accords it legal status? Well, not quite yet.

Table: The first four Neighbourhood Plan referendums

The NDP is a professionally prepared document, replete with a vision, objectives, a strategy, implementation plan, and six clear policies on various aspects of community life – the unquestionably key one being Housing Growth. There are currently 1,090 homes in Tattenhall and the Plan proposes allowing up to 30 new homes in the built-up village in the period to 2030, plus limited smaller scale development elsewhere in the parish.

Three national housebuilders, however – Wainhomes, Barratts, and Taylor Wimpey – have applied to build a total of 305 homes in what the Plan rejects as “large-scale inappropriate development along existing village boundaries”. The builders contest aspects of the Plan and also the independent examiner’s impartiality, and have lodged a judicial review challenge, which, until the High Court deliberates, will prevent the Plan being formally adopted and joining what Planning Minister Nick Boles has called the quiet planning revolution.

He used the phrase back in March to describe the almost equally positive outcome of the first referendum in, appropriately enough, Eden – though not the Garden thereof, but Eden Valley to the east of the Cumbrian Lake District. The Upper Eden NDP is quite different from Tattenhall’s – not least because the area is extremely sparsely populated and about 17 times Tattenhall’s size.

Again, housing is the Plan’s main focus, but the proposed development rate here is 40 homes a year, and 545 over the plan period to 2025 – higher than the 479 total in the district council plan, with all 66 extra homes allocated to rural areas that the constituent parishes felt had previously been overlooked. Other policies include increasing affordable rural housing by permitting more conversions, incentivising developers to provide more housing for older people, and improving broadband provision. This being the first NDP referendum, there was a lot riding on it, not least for Ministers, and Upper Eden delivered. In a 34% turnout – nearly double that in Cumbria’s police commissioner election last November – 90% backed the Plan.

The St James area of Exeter, site of the next plan that went to referendum, is completely different again: 6,000 residents sandwiched between the city centre and university campus in a community that has been losing its traditional, diverse character through the intrusion of traffic and car parks, neglect of green space, but particularly the conversion of family homes into houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) – student occupation.

The NDP was prepared by the Exeter St James Forum, a group of local people, including representatives from the Students’ Guild. Key policies included restricting the spread of HMOs and bringing more social balance to the area, encouraging small businesses, a tree planting campaign, and identifying certain residential streets for ‘home zone’ treatment with reduced and slowed traffic. In a May 2nd vote in a student-dominated ward, turnout was an unsurprisingly disappointing 21%, but the endorsement of the Plan a steamrollering 94%.

The last of the four NDP referendums to have taken place so far was held on the same day, in the South Oxfordshire market town of Thame, and we have another quite different scenario. For Thame’s NDP was a direct response to the core strategy in South Oxfordshire’s local plan, which proposed allocating 600 homes on one large site on the outskirts of the town, rather than, as many residents seemingly preferred, on developable sites within the town itself.

The district council, to its credit, backed Thame Town Council’s bid for funding to produce its own NDP, on the understanding that it could cover only non-strategic issues and not, for instance, the numbers of proposed homes. Advised by professional urban designers, the town council consulted with residents, identified more than enough potential sites, and eventually agreed on a ‘Walkable Thame’ option: all new homes to be within walking distance of Thame town centre.

In the May referendum it was approved by a more than 3 to 1 majority on a nearly 40% turnout. As the local media justifiably boasted, Thame residents had become the first in England to pick their own housing sites through a neighbourhood plan.

Three more referendums are currently lined up, but this is a trickle with the potential to become a flood. There are now well over 600 recognised Neighbourhood Planning Areas, and Ministers claim over half of English local authorities are working with groups on community planning. It’s far too early to draw any serious conclusions – as to whether neighbourhood planning will constitute a quiet revolution or anything else. But one almost instant criticism of NDPs was that they would appeal most to parish and town councils in relatively less deprived rural areas in the already over-heated south-east. It may well prove to be true, but the four very disparate Neighbourhood Plans to have come almost arbitrarily to referendum so far offer little support.

—

Note: This post was originally published on the INLOGOV blog. It represents the views of the author, and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Shortlink: https://buff.ly/HRASae

—

Chris Game is an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham.

Chris Game is an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Neighbourhood planning about democracy as well as place-making https://t.co/ESkx5AKXFh #neighbourhoodplanning @npResearchNet