How democratic are the UK’s political parties and party system?

As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Sean Kippin, Patrick Dunleavy and the DA team examine how democratic the UK’s party system and political parties are. Parties often attract criticism from those outside their ranks, but they have multiple, complex roles to play in any liberal democratic society. The UK’s system has many strengths, but also key weaknesses, where meaningful reform could realistically take place.

A Unite band plays during Labour’s 2015 election campaign. Photo: Labour Party via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

This is an old version of this article. An updated, 2018 edition is available here. You can also download the full 2018 Democratic Audit from LSE Press here.

What does democracy require for political parties and a party system?

Structuring competition and engagement

- The party system should provide citizens with a framework for simplifying and organising political ideas and discourses, providing coherent packages of policy proposals, so as to sustain vigorous and effective electoral competition between rival teams.

- Parties should provide enduring brands, able to sustain the engagement and trust of most citizens over long periods.

- Main parties should help to recruit, socialise, select and promote talented individuals into elected public office, from local council to national government levels.

- Party groups in elected legislatures and outside organisations should help to sustain viable and accountable leadership teams, and contribute to the scrutiny of public policies and elected officials’ behaviour, in the public interest.

Representing civil society

- The party system should be reasonably inclusive, covering a broad range of interests and views in civil society.

- Dissatisfied citizens should be able to form and grow new political parties easily, without encountering onerous or artificial official barriers.

- Regulation of party activities should be independently and impartially conducted to prevent self-serving protection of existing incumbents.

Internal democracy and transparency

- Long-established parties inevitably accumulate discretionary political power in the exercise of these functions, creating citizen dependencies upon them and oligopolistic effects in restricting political competition. So to compensate, their internal leadership and policies should be responsive to a wide membership that is open and easy to join.

- Leadership selection and the setting of main policies should operate democratically and transparently to members and other groupings inside the party (such as party MPs or members of legislatures). Independent regulation should ensure that parties stick both to their rule books and to public interest practices.

Political finance

- Parties should be able to raise substantial political funding of their own, but subject to independent regulation to ensure that effective electoral competition is not undermined by inequities of funding

- Individuals, organisations or interests providing large donations must not gain enhanced or differential influence over public policies, or the allocation of social prestige. All donations must be transparent.

Recent developments

Political parties in the UK are normally stable organisations. Their vote shares and party membership levels typically alter only moderately from one period to the next. But after 2014, party fortunes changed radically. At the 2015 general election support for the Liberal Democrats fell to a third of its 2010 level, and their tally of MPs plunged from 57 to 8 (now 9, following the Richmond by-election). Voters punished them for supporting to the end the Cameron-Clegg, Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government. The more resilient Tory machine relentlessly captured most seats from their erstwhile, now embattled partners. The party is fighting the 2017 General Election on an anti-Brexit platform, and achieved a national vote share of 18% in the 2017 local government elections, a possible sign of revival also reflected in party members passing 101,000 in the same month.

In Scotland, the SNP built on its mobilisation during the 2014 referendum campaign to take all but three Westminster seats there in 2015. Labour’s vote in Scotland plunged from 42% in 2010 to 24% per cent, and under plurality rule voting its MPs there fell from 41 to just one. The First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, has made clear her opposition to a hard Brexit and her determination to hold a second independence referendum, but polls continue to show a majority of Scots favour the Union.

Following Ed Miliband’s resignation, a lacklustre Labour leadership competition revealed a gulf between Labour’s parliamentary party (PLP) and most of its members (recently enlarged by the introduction of a £3 membership fee). A wave of younger people getting involved, and of disillusioned older, left-wing supporters rejoining, lead to the complete outsider Jeremy Corbyn becoming leader, winning clear overall majorities amongst new members, old members and trade union members. He quickly faced serious problems in constructing a shadow Cabinet and maintaining the loyalty of Labour MPs. Following the Brexit referendum, when Corbyn only vaguely supported ‘Remain’, the PLP majority tried to out him from office by deserting his shadow Cabinet and triggering another leadership contest (lead by Owen Smith). However, Corby won this new challenge easily (getting 62% support), and he survived with enough loyalist MPs to just about staff his front bench. Nonetheless, the majority of the PLP continue to oppose Corbyn’s leadership, but have preferred to wait for him to fail rather than splitting the party.

In June 2015 David Cameron’s premiership had looked assured until at least 2018, although a few voices foresaw trouble ahead. But after losing the EU referendum, he stood down and was replaced by Theresa May after a confused process where the Tories began a messy-looking leadership competition, and then aborted it almost as soon as it began by all the rivals to May withdrawing from competition. The May government subsequently endorsed an apparently ‘hard’ Brexit strategy, which embraced the Eurosceptic wing of the party, while promising ‘fairness’ for ‘ordinary’ Britons and decrying the influence of a rootless international elite.

The most chaotic political party has been Ukip. The party polled far better in 2015 than previous general elections, retaining nearly 13% support from its high water mark in the 2014 European Parliament elections. But disappointments over its failure to win any new MPs under plurality rule created party in-fighting and tensions between the party leader, major donors and its solitary MP. After the EU referendum, Nigel Farage stood down, declaring his work was done. His successor elected by party members was Diane James, but she stayed in post for only 18 days, quitting suddenly over party in-fighting. She was followed by Paul Nuttall, who stood in a Westminster by-election in Stoke, only to fail ignominiously in his hope of ousting Labour there. In early 2017, the party’s sole MP Douglas Carswell announced he would quit the party. Ukip now finds itself outflanked by the Conservatives on the subject of the EU, and lost all the council seats it contested in May 2017, with its national vote share plunging to only 6%.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Britain’s party system is stable, and the main parties generally provide coherent platforms consistent with their ‘brand’ and ‘image’. | Party membership in the UK is low. Around 950,000 people are members, out of a population of 65.6 million. |

| Britain’s political parties continue to attract competent and talented individuals to run for office. | Plurality rule elections privilege established major parties with strong ‘safe seat’ bastions of support, at the expense of new entrants. |

| Entry conditions vary somewhat by party, but it is not difficult or arduous to join and influence the UK’s political parties. Labour has opened up the choice of their top two leadership positions to a wider electorate using their existing trade union networks and a new £3 supporter scheme. (However, this has caused tensions with the party’s MPs). | The most active political competition thus tends to be focused on a minority of around 120 marginal seats, with policies tailored to appeal to the voters therein. |

| The UK’s main political parties are not over-reliant on state subsidies and can generally finance themselves either through private and corporate donations, or (in Labour’s case) trade unions funding. | It is fairly simple to form new political parties in the UK, but funding nomination fees for Westminster elections is still costly. And in plurality rule elections new parties with millions of votes may still win no seats, as happened to UKIP in 2015. |

| In the restricted areas where it can regulate the parties, the Electoral Commission is independent from day-to-day partisan interference. | The ‘professionalisation of politics’ is widely seen as having ‘squeezed out’ other people with a developed background outside of politics (but see below). |

| Most mechanisms of internal democracy have accorded little influence to their party memberships beyond choosing the winner in leadership elections themselves. Jeremy Corbyn claims to be counteracting this and listening more to his members. However, in consequence, Labour is struggling to delineate the relationshipbetween MPs in the parliamentary party (answerable to voters) and the enlarged membership (wh0 may not reflect Labour voters’ views well). | |

| There are large inequities in political finance available to parties, with some key aspects left unregulated. These may distort political (if not) electoral competition. Majority governments can alter party funding rules in directly partisan and adversarial ways (see below). |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The UK’s continued evolution towards multi-party politics has found expression in elections beyond Westminster and English local government. New and ‘outsider’ parties strengthen anti-oligopoly tendencies and future electoral reforms may generate some further momentum here. | In multi-party conditions, plurality rule elections for Westminster may operate in ever more eccentric or dramatic ways, as with the SNP’s 2015 landslide in Scotland almost obliterating every other party’s MPs there. |

| Some ‘new party’ trends have emerged within Labour and the SNP that might strengthen ties with civil society, or alternatively ebb away again (see below). | Moves by governing political parties to alter laws, rules and regulations so as to skew future political competition and disadvantage their rivals can set dangerous precedents that degrade the quality of democracy. The Conservative government changes to electoral registration and redrawing of constituency boundaries may all have such effects, even if implemented in non-partisan ways. |

| The advent of far greater ‘citizen vigilance’ operating via the web and social media like Twitter and Facebook creates a new and far more intensive ‘public gaze’ scrutinising parties’ internal operations. Tools such as ‘voting advice’ application apps or the Democratic Dashboard also allow voters to access reliable information about elections and democracy in their area - information that neither government nor the top parties the state has so far either been able or willing to provide. | The SNP’s successes have created a ‘dominant party system’ system in Scotland, where party alternation in government ceases for a long period. If their now fragmented opposition cannot unite to offer a credible alternative government, good governance may suffer. |

| Digital changes also open up new ways in which parties can connect to supporters beyond their formal memberships and increase their links to and engagement with a wider range of voters. Parties now generally conduct their leadership elections using an online system which makes it easier to register a preference. Other matters of internal party business and campaigns could soon be affected, potentially including setting policy. | The growth of political populism and identity divisions post-EU referendum has ‘hollowed out’ the centre ground of British politics, with the Liberal Democrats unable to regain their earlier momentum. |

| All the UK’s different legislatures (Westminster, and the devolved assemblies/parliaments in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and London) have now sustained coalition governments of different political stripes and at different periods, and each has operated stably. So the UK’s adversarial political culture does not rule out cross-party cooperation where electoral outcomes make it necessary. |

Structuring competition and party ‘brands’

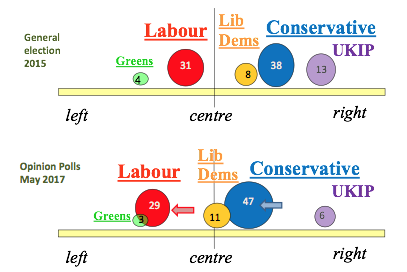

In terms of the parties’ ideological appeals and relative standing, Chart 1 shows that for the party system in England the left-right scale still remains the key organising frame for party competition, weakened though it may be. Recent changes (covered above) continue the trend of several decades towards the UK approximating the pattern found across western Europe where an (often declining) social democrat party linked to trade unions faces a main political centre-right party – with an anti EU/anti-immigration party (here UKIP) further to the right; a small, squeezed liberal party; and a green party presence on the left (weaker in the UK than elsewhere). The second part of Chart 1 shows the extent of changes apparent since the general election, including the Tory centre-wards move and Labour’s shift further left under Corbyn. If this pattern continues, given the operations of plurality rule in Britain, and Labour’s retreat in Scotland, a period of Conservative predominance looks likely.

The main alternative dimension in England has been the pro and anti-EU one, increasingly overlapping in UKIP’s campaigning with anti-immigrant sentiments. Both the top two British parties have had chronic difficulties in organising around this aspect of politics, although Labour has become progressively more pro-EU and the Conservative MPs (if not their leadership) have become more anti-EU and pro-Brexit. Attitudes towards immigration are far more aligned with existing left-right cleavages, especially as Labour has developed towards being more of an urban/multicultural party.

Chart 1: Changes in the party system in England, from June 2015 to May 2017

Source: P. Dunleavy. The positions of party ‘blobs’ show their approximate left/right position; the size of blobs shows indicates their levels of opinion poll support.

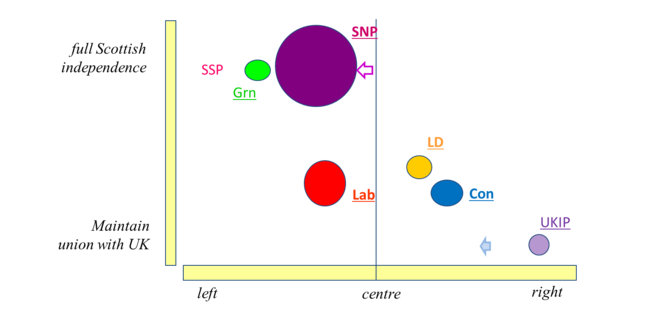

By contrast, in Scotland devolution and independence create a second key ideological dimension of politics, as salient (or perhaps more salient) than left/right cleavages. For some time this benefited the SNP (and Scottish Greens in a minor way), by tending to undermine and push together the other four parties that campaigned to keep the union with the UK in 2014. The SNP lost that referendum, but they gained a pre-eminence as the ‘voice for Scotland’ that remains a big electoral advantage. Chart 2 also shows that the left/right centre of gravity is more to the left in Scotland, with polls approximating 50% SNP support, Labour reduced to less than a 25% polls share now, and four other parties (including a more vigorous Green party and a diminished UKIP) contending for the remaining support.

Chart 2: The Scottish party system at the 2015 general election

However, the danger of Scotland becoming a ‘dominant party system’ – where the same party is a serial winner against a fragmented opposition incapable of co-operating to defeat it – perhaps receded in 2016-17. After Scotland voted decisively to remain in the European Union, the SNP leadership attempted to negotiate a partly different ‘Brexit’ solution from the rest of the UK, a move that the May government decisively rejected, prompting SNP calls for a second independence referendum that were not initially popular with Scottish voters. A referendum was eventually confirmed by Nicola Sturgeon, but rejected by May before the end of the Brexit process, and stoutly resisted by the Scottish Tories under Ruth Davidson. At the Scottish Parliament elections in 2016 there were signs of pro-Union voters for Labour and the Liberal Democrats shifting to the Tories (in addition to UKIP withering away), and in the May 2017 Scottish local government elections the Tories pushed a weakened Labour into third place across Scotland, although with the SNP remaining clearly ahead.

The enduring quality of parties’ appeals is borne out by recent research showing that strong party supporters place themselves ideologically at the same place as the parties they identify with. Supporters tend to accurately perceive their own party’s position, but to see opposing parties as more ‘extreme’ than they are. On the centre-left there were multiple overlaps of party supporters’ views amongst Labour, the Greens and Liberal Democrats, while on the right the Conservatives and UKIP overlapped in some anti-EU positions.

Yet in mid-terms, between general elections, around two-fifths of those backing major parties told IPSOS-MORI they did not know what they stood for. So are main parties failing to communicate their brands in a sustained and consistent manner? A potential explanation may lie with the various processes of party ‘modernisation’ that took place over recent years, with each of the three main parties attempting to ‘move to the centre’. The shifts to a more ‘managerialist’ politics of detail that occurred before Corbyn, the EU referendum and May’s realignment of the Tories may have left many voters less clear what each party advocates. But the reconfiguration of British party politics since 2016 now suggests that a realignment of the party system may be in train – with UKIP potentially eliminated to the Tories’ great benefit.

Representing civil society

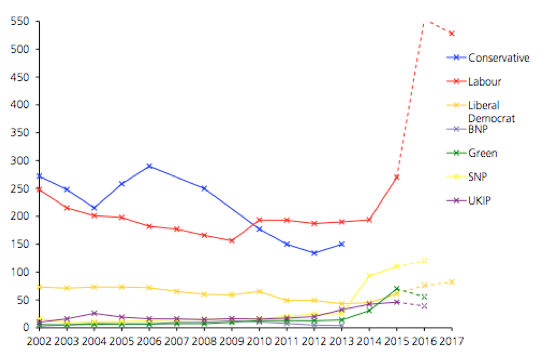

The standard theme of textbook discussions is that the major political parties are declining in their ability to recruit members, and thereby becoming ‘cartel parties’ dependent for their lifeblood upon large donors (such as very rich individuals for all parties, or trade unions with large membership blocs for Labour), or upon state subsidies to parties. Yet Chart 3 shows that this narrative of continuous decline has not been accurate for British parties as a whole in the twenty-first century.

Chart 3: The membership levels of UK political parties since 2001

Source: House of Commons Library; Note: the vertical axis here shows thousands of members. Dotted lines show estimates based on media reports and party press releases.

The last two years in Chart 3 also show soaring numbers of members for the SNP since the independence referendum campaign of 2014 and of the Labour party since easier membership rules, low cost fees, and the post-general election changes. Some observers point out that with 517,000 individual members, a Corbyn-led Labour would also gain perhaps £8 million in annual fees, and be able to reduce its dependence on affiliated trade unions’ block fee payments – although the threat of legislation mandating that union members ‘opt in’ to paying political levies, instead of ‘opting out’ as at present, has receded.

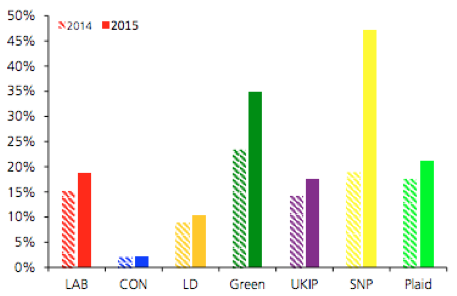

All these changes mean that parties now draw very different proportions of their income from membership subscriptions. The Greens and SNP are the parties for whom membership fees count most as a source of income, with the Conservatives bottom.

Chart 4: Income from membership revenues as a percentage of total income

Source: Party annual accounts submitted to the Electoral Commission

In some European countries, a recent rejuvenation of party politics has taken two contrasting forms – with new left parties committed to a different kind of ‘close to civil society’ politics emerging on the left (like Podemos in Spain), and populist, anti-EU/anti-immigration parties growing on the radical right. Some observers even discern the ‘death of representative politics’ in such changes. But in the UK the highly insulating plurality rule voting system at Westminster has asymmetrically protected the top two UK parties, with the UKIP wave artificially excluded from Parliament on the right in 2015. And left-of-centre movements have happened not in new parties but within the ranks of Labour (in England) and the SNP (in Scotland). These latter changes may not endure, however, with the SNP reverting to ‘normal’, less energising status, and the Corbyn period potentially coming to an end in intra-party divisions.

Electing party leaders, or not

For a brief period in the 2010s all the parties enacted protracted processes in which their mass memberships would elect the party leaders, albeit from fields of contenders that were initially defined by MPs. Yet these arrangements now look as if they are likely to change or fall into abeyance. In June 2016, following Cameron’s shock resignations, complex politicking amongst Tory MPs saw a field to replace him that mysteriously excluded two ‘big beasts’, Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, who were going to run on a joint ticket, but who ended up falling out, with Johnson not even making the nominations stage. That left – as well as frontrunner Theresa May – two low-chance Brexiteers (Andrea Leadsom and Liam Fox) and a little known centrist (Stephen Crabb). All three rivals to May subsequently withdrew, making May the unelected but unquestioned leader, the MPs’ fix denying members any chance to vote.

When the Liberal Democrats came to elect a new leader after their 2015 general election losses they did run an election, but members had effectively little choice since the party had only 8 MPs left in the Commons.

Meanwhile the election of Jeremy Corby in 2015 reflected a different kind of fix. The Labour left had insufficient MPs to meet the 15% of the PLP needed to secure his nomination, and only just prevailed on some centre-right MPs (including Margaret Beckett) to sign his nomination papers so that he could compete. In 2016 an attempt to keep Corbyn off the leadership challenge election forced by the PLP, by forcing him to get 15% of MPs to nominate him again, narrowly failed in the Labour National Executive Committee – Corbyn argued that as sitting leader he did not need to be re-nominated by MPs under Labour’s rules, but had automatic entry into the election. After the 2017 general election the centre-right of the PLP is seeking to reintroduce the Electoral College that Labour operated in the 1990s and 2000s, in which MPs have a third of the votes, along with trade union members and constituency party members. Meanwhile the left, who are strongly represented on the party’s National Executive Committee want to keep the current system but cut the percentage of the PLP needed for a candidate to qualify, fearing that otherwise the ‘Corbyn opportunity’ will never arise again.

Recruiting political elites

The main political parties maintain a steady stream of individuals to run for political office, who can be socialised, selected, and promoted into their structures. However, the impression has gained ground that increasingly parties are bringing forward candidates with professional, back-office backgrounds as candidates. In fact, such ‘politics professionals’ make up less than one in six MPs, far lower than popular accounts envisage. However, it is true that ‘MPs who worked full-time in politics before being elected dominate the top frontbench positions, whilst colleagues whose political experience consisted of being a local councillor tended to remain backbenchers’. So politics professionals within the top parties do tend to dominate media and policy debates.

In terms of wider social diversity, the 2015 parliament is in some ways (notably gender and ethnicity) the most diverse and representative ever. Yet as Campbell et al noted: ‘To put the progress made in perspective, the UK would need to elect 130 more women and double the current number of black and ethnic minority MPs to make its parliament descriptively representative of the population it serves.’

Internal democracy

All the parties have moved to greater transparency and openness in their affairs, and have different arrangements for intra-party democracy to periodically c set aspects of party policy. Labour’s widening of membership and election of the party’s National Executive Committee by members is the most radical innovation, and has created a left majority under Corbyn.

The remaining parties still operate more orthodox arrangements. In theory Liberal Democrats have the most internally democratic party, with the federal party and party conference enjoying a pre-eminent role in policy formation. Yet in the coalition period the exigencies of the party being in government seemed to easily negate this nominal influence (as has long been argued to be the case in the top two parties). The Conservative Party meanwhile enjoys relatively little influence over party policy with decisions being made largely in Cabinet or Shadow Cabinet, and to a lesser degree by the national party machine. At local level, members have more influence but they rarely challenge sitting MPs. UKIP’s members are not empowered by their party’s constitution, which declares that motions at conference will only be considered as ‘advisory’, rather than binding. The Green Party probably allows its membership the greatest degree of influence over internal policy.

Political finance

The core foundations of the UK’s party funding system lie outside the parties themselves in electoral law. Two key provisions are (i) the imposition of very restrictive local campaign finance limits on parties and candidates; and (ii) the outlawing of paid-for any broadcast advertising by parties in favour of state-funded and strictly regulated party election broadcasts (related to votes won last time). Opposition parties also have the benefit of a degree of state funding (again related to votes received) but this is only available to those parties with at least one MP in Parliament. However, the Green Party and UKIP have begun to receive funding on this basis since 2010 and 2015 respectively. The main effect so far has been to fund the leaders’ offices of Labour and the SNP.

Political finance nonetheless still matters immensely in UK politics because two types of spending are completely uncontrolled, namely (iii) supra-local campaigning and advertising in the press, billboards, social media and other generic formats; and (iv) general campaign and organisational spending by parties, which is crucial to parties’ abilities to set agendas and create media coverage ‘opportunities’, especially outside the narrowly defined and more media-regulated election periods themselves. Table 1 shows that the Conservative Party gained 47% of all private donations over the 2013-16 period, mostly from very rich people. Labour, meanwhile, gained a smaller 33%, partly from trade union fees and from large donations. The Liberal Democrats, in government until 2015, also gained some large gifts – as did UKIP.

Table 1: Donations to political parties 2013-16

| Party | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2013-16 (% of all donations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | £15.9m | £29.2m | £33.2m | £17.5m | £95.8m (47%) |

| Green | £190k | £662k | £428k | £184k | £1.5m (0.7%) |

| Labour | £13.3m | £18.7m | £21.5m | £13.9m | £67.4m (33%) |

| Lib Dems | £3.9m | £8.3m | £6.7m | £6.4m | £25.3m (12.5%) |

| SNP | £44k | £3.8m | £1.2m | £143k | £5.6m (2.7%) |

| UKIP | £669k | £1.2m | £3.3m | £1.6m | £6.8m (3.4%) |

| Total | £34m | £62m | £66m | £40m | £202m (100%) |

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding. Source: Electoral Commission

Donating to parties is supposedly transparent. All gifts must be declared and sources made clear, and funding is regulated by the Electoral Commission. But unlike many liberal democracies, there are no maximum size limits on UK donations, although donations from overseas have been clamped down on. Critics argue that ‘the fact that political parties are sustained by just a handful of individuals makes unfair influence a very real possibility even if the reality is a system that is more corruptible than corrupt.’ Close analysis also shows a strong link between donations to political parties and membership of the House of Lords, now almost entirely in the gift of party leaders. Despite supposedly stronger rules applying to ‘good conduct’ in public life (following scandals around 2009) Conservative and Labour leaders have both been very reluctant to give up the lubricating role of the honours system in sustaining their funding hegemony and easing internal party management. And the Liberal Democrats have far and away the highest ratio of peerages and knighthoods amongst their (now largely former) MPs, of any UK political party.

Although party finance regulation is impartially implemented in a day-to-day manner, there is little to stop a government with a majority from legislating radically change party finance rules in ‘sectarian’ ways that maximise their own individual party interests and directly damage opponents. In 2016 the Conservatives unilaterally brought forward proposals to force all trade union members of the Labour party to actively ‘opt in’ to membership, disrupting a lackadaisical and much-blocked cross-party effort to reach agreement on ways of limiting and diversifying donations to national parties. In the UK’s ‘unfixed’ constitution, only elite self-restraint, Tory party misgivings or perhaps House of Lords changes can prevent directly partisan manipulation of the opposition’s finances.

Conclusion

The conventional wisdom of ‘parties in decline’ does not now fit the recent history of the UK well, with some membership levels growing, and others fairly stable. Some ‘new party’ trends emerged (for a while) within Labour and the SNP, utilizing different, more digital ways of mobilising and stronger links to parts of civil society. Internal party elections of most key candidates (not leaders) are generally stronger now than in earlier decades (except within UKIP). So parties are not yet just the self-serving ‘cartels’ that critics often allege.

Yet many problems remain. The provisions for party members to elect leaders were left unused in the Tory party in 2016, and have created almost insupportable strains for Labour under Corbyn. The problem of a ‘club ethos’ uniting MPs in the main parties was exemplified in April 2017 by Labour leaders and MPs joining the Tories in calling a general election. It is also evident in the over-protection that the Westminster election system grants Conservatives, Labour and now the SNP; in the very partial regulation of political financing and the (only weakly regulated) effective ‘sale’ of honours; in the ability of governments to legislate in sectarian ways to weaken their opposition parties; in weak internal party controls or influence over policy stances and manifestos; and in the sheer scale of parliamentary party remoteness from membership views, demonstrated by Labour’s leadership contests in 2015 and 2016.

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE, co-director of Democratic Audit and Chair of the Public Policy Group.

Sean Kippin is a PhD candidate and Associate Lecturer at the University of the West of Scotland and a former editor of Democratic Audit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and party system? https://t.co/raZvcbahej

[BLOG] #UK: Check out @democraticaudit’s SWOT analysis of #PoliticalParties & the UK party system. https://t.co/Dp9d0V18FU

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and party system? https://t.co/3khsS3PwxQ

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and the party system https://t.co/UwOwCPC7T7 https://t.co/9j9PxcIHeP

How democratic are the UK’s political parties & party system? Latest post in 2016 audit, by me and @PJDunleavy https://t.co/8NjuAAnivJ

How democratic are the UK’s political parties & party system? Latest post in 2016 audit, by @se_kip & @PJDunleavy https://t.co/w65d8PxLDD

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and party system? a survey of strengths and weaknesses. https://t.co/RMOoXa6tim

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and the party system https://t.co/9xYHVf4sK8 https://t.co/f05g96xs3O

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and the party system https://t.co/RMOoXa6tim

How democratic are the UK’s political parties and the party system https://t.co/vN8Qqigtq5 https://t.co/2myIeY2j2F