How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens?

As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Artemis Photiadou and Patrick Dunleavy consider how well the House of Commons functions as a legislature. Is Parliament still an effective focus of national debate and close control of the executive? And how well does the Commons function in scrutinising and passing legislation, or monitoring policy implementation?

Commons speaker John Bercow takes the Chair in 2010. Photo: UK Parliament via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

This is an old version of this article. An updated, 2018 edition is available here. You can also download the full 2018 Democratic Audit from LSE Press here.

What does democracy require for the legislature in focusing national debate, and scrutinising and controlling major decisions by the executive?

- The elected legislature should normally maintain full public control of government services and state operations, ensuring public and Parliamentary accountability through conditionally supporting the government, and articulating reasoned opposition, via its proceedings.

- The House of Commons should be a critically important focus of national political debate, articulating ‘public opinion’ in ways that provide useful guidance to the government in making complex policy choices.

- Individually and collectively legislators should seek to uncover and publicise issues of public concern and citizens’ grievances, giving effective representation both to majority and minority views, and showing a consensus regard for the public interest.

How should the legislature operate in passing laws and controlling the executive’s detailed policies?

- In the preparation of new laws, the legislature should supervise government consultations and help ensure effective pre-legislative scrutiny.

- In considering legislation Parliament should undertake close scrutiny in a climate of effective deliberation, seeking to identify and maximise a national consensus where feasible.

- Legislators should regularly and influentially scrutinise the current implementation of policies, and audit the efficiency and effectiveness of government services and policy delivery.

Recent developments

The first peacetime coalition since 1945 between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats marked out 2010-15 as an unusual period of Parliamentary relations with the government. Ministers (especially David Cameron as Prime Minister) were uniquely exposed to right-wing Tory backbenchers and centre-left Liberal Democrats dissenting from government policies. Not surprisingly, Phil Cowley showed that backbench dissent affected 35 percent of Commons divisions 2010-15, a post-war record (with the Labour government of 2005-10 as the nearest parallel). A new ‘hung Parliament’ situation arose after the failure of Theresa May’s June 2017 general election bid. Her new minority Conservative government is reliant on a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement with the 10 MPs of the DUP. Most predictions are that it will be vulnerable to more backbench revolts (and indeed to defeats), because Tory MPs in particular have now got the habit of dissenting. Early indications seemed to bear this out. In the Queen’s Speech debate in June 2017, Labour backbencher Stella Creasy tabled a relevant amendment to fund abortion operations in mainland UK for women from Northern Ireland. This would have been supported across the House had it gone to a vote, and so the government was forced to agree to the change in order to avoid a defeat.

However, some potentially key changes in parliamentary operations also survived from the 2010-15 coalition government period. The Fixed Term Parliaments Act 2011 formally requires that general elections are held every five years, unless the government loses a vote of confidence and no other government can be formed, or unless two thirds of MPs vote for an earlier dissolution. This was seen as a key safeguard against Cameron calling an election early by the Liberal Democrats, but it actually did little to prevent their electoral punishment at the end of the government’s enlarged term in 2015. With Cameron’s victory in 2015 the Act initially made the Tories look like a strong beneficiary, with a five-year term apparently securely guaranteed. But May’s miscalculation in calling an early election for June 2017, which resulted in the loss of Cameron’s slender majority, meant that things turned out differently. In April 2017 when May demanded the election, the Tories were 20 points ahead of Labour in opinion polls, whose MPs nonetheless voted for an immediate context – vindicating Jeremy Corbyn’s judgment in this case.

Another legacy of the coalition era was that a significant parliamentary boundaries review to cut MPs’ numbers from 646 to 600 and to fine-tune equally-sized constituencies was canned in 2012 by the Liberal Democrats, after Cameron proved unable to keep his promises on Lords reform because of Tory backbench resistance. But when (thanks to the first past the post electoral system) the Conservatives won an outright (if wholly artificial) majority of MPs in 2015, the scheme was dusted off and implementation began – which is likely to boost Tory MPs by around 20 at the other parties’ expense. The Boundary Commission for England must submit its report by September 2018 and, if approved by Parliament, the new constituencies will be used in the next election after the approval. However, the febrile conditions of a hung Parliament, and the probability that some Tory members may want to postpone changes that damage their seat, mean that the outcome here is no longer guaranteed.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

Current strengths Current weaknesses The House of Commons’ long history and central cross-national position as an exemplar of sound Parliamentary practice give its members a strong sense of corporate identity, motivating some public interest behaviours. The Commons is executive-dominated, with MPs most often voting on ‘whipped’ partisan lines. Party cohesion has weakened, but is still exceptionally high by cross-national standards.Committee scrutiny of legislation via partisan whipped bill committees (with inexpert MPs) is always ritualistic, ineffective and normally of very little value. Some parliamentary institutions operate effectively, engaging the attention of MPs, media and the public – especially PM’s Question Time (and to a lesser degree, ministers’ question times), and the operation of select committes. The Commons’ ex ante budget control is non-existent. Finance debates are simply political and general talk-fests for the government and opposition. Parliamentary ‘estimates’ are odd and out of date numbers, of declining value in relation to the real dynamics of public spending. The collaboration of government and opposition is in some respects exclusionary, but also contributes to a certain degree of elite self-restraint and avoidance of rancorous partisanship that is essential to the operations of the UK’s ‘unfixed’ constitution. Only a few component parts of the legislature’s activities work well, and much of the time its behaviours are ritualistic, point-scoring and unproductive in terms of achieving policy improvements – e.g. anachronistic and time-wasting division vote procedures in a digital era. Most attempted modernisations remain stalled on traditionalist MPs’ objections. MPs’ small constituencies have fuelled their role as grievance-handlers for constituents having trouble with public services, which has expanded in recent years. The top two parties are not only normally over-represented in terms of MPs vis-a-vis their vote share, but also collude to run Westminster business as a club in their partisan interests (e.g. via archaic bodies like the Privy Council). The views of smaller parties and parties left unrepresented despite substantial vote shares are systematically excluded from Parliament. The post hoc auditing of spending via the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) has some strengths. The Commons meets in a museum building, surrounded by a Victorian empire grandeur that helps perpetuate a culture amongst MPs that is always male-orientated, white, club-like, and obsessed with the ‘privileges’ of MPs. Debates and other sessions are often ‘shouty’ and visibly anti-deliberative. Select committees’ roles and public visibility have both expanded in recent years, and the ‘Wright reforms’ have been effective modernisations. On matters affecting their own welfare, MPs are self-governing, self-interested and routinely dismissive of ordinary citizens’ concerns (c.f. repeated MPs’ expenses scandals and recent austerity-busting pay rises). The Liaison Committee sessions with the PM are a useful if modest innovation. The House of Commons (at 646 MPs) is an exceptionally large legislature. Most MPs don’t have enough useful things to do (hence the still frequent second jobs and ethically dubious ‘outside interests’). The government has created a huge ‘payroll vote’ of ministers and pseudo-ministers simply to help maintain control of these excess numbers by dangling a chance for preferment. The Backbench Business Committee enables backbenchers to raise topics for debate in a more effective way. Fuelled by the coalition period, and now the Tories’ narrow majority, the amount of secondary legislation is growing, and primary legislation is drafted in ways that increasingly leave its consequences obscure, to be filled in later via statutory instruments or regulation. Commons scrutiny of such ‘delegated legislation’ is very weak and ineffective. MPs can raise issues with the government though Early Day Motions, very few of which are ever debated. Many topics tend to be trivial. The Procedure Committee in 2013 nonetheless found that there should be no changes. EDMs have generally declined.

Current opportunities Current threats Moves to make the Commons more family-friendly and its culture more diverse are having some success, but much more can be done at zero cost. In 2015 the incoming Tory government proposed 19% cuts in the state funding given to opposition parties (known as Short money), a move that will inhibit their ability to conduct parliamentary business and critique ministers effectively, without making any worthwhile savings. Its status at mid 2017 seems unclear. The DUP, despite their confidence and supply agreement with the government, also continue to benefit from Short money meant for the Opposition. Funnelling all the post hoc financial scrutiny of public spending through only one committee (PAC) wastes much of the work of the National Audit Office (NAO) in scrutinising the civil service. Single department and smaller spending NAO reports should be run through Select Committees. The PAC should focus more on cross-departmental, inter-governmental and major spending areas. Enacting the EVEL change via changing Commons’ standing orders sets a thoroughly dangerous constitutional precedent, outside all judicial review. If a Commons majority alone can tell MPs in one part of the country that they cannot vote in a newly created but decisive Westminster procedure, what is to stop another majority imposing the same exclusion on MPs of a given party? Select Committees need to move away from sole reliance an out-of-date evidence-gathering process focusing only on calling witnesses and use NAO staff to produce meaningful research of their own on policy effectiveness. Both this and the previous point would cost almost nothing to implement. The almost non-representation of UKIP in the Commons, and of non-SNP parties in Scotland, further reduces the legislature’s already tattered representativeness under first-past-the post voting. Limits on MPs’ self-government need to be further strengthened. The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee was a potent force for modernisation 2010-15, including within the Commons. In June 2015 it was abolished and its constitutional role kept only as a small sub-section of the Public Administration and Constitution committee. E-petitions give the public a new opportunity to raise issues with the government by triggering a parliamentary debate if 100,000 signatures are obtained. By July 2017, over 31,730 petitions had been launched, two thirds of which were rejected, while 56 have been debated in Parliament and nine will soon be. So far this popular option has proved inconsequential in changing policies, though it is an effective way of raising public awareness or showing public discontent. If and when a Brexit agreement is reached, current EU law in force in the UK will need to be converted into domestic law (and in certain cases be 'corrected' before being converted). Such changes, as proposed in the Repeal Bill, will be made by ministers and not be subject to the usual parliamentary scrutiny. The Lords Constitution Committee called this prospect a 'massive transfer of legislative competence’ into the Government's hands. It raises major questions about the right balance between executive and legislature power, especially in the period 2017-20. The Parliament website is very large but hard to use. Many MPs and Select Committees have only made limited steps to connect with voters via social media. Parliamentary consideration of treaties and military actions

The Royal Prerogative consists of those powers of the medieval absolute monarchs that are not yet regulated by statute law. They are exercised on the Crown’s behalf by ministers, especially the PM. Historically the PM and government have retained the prerogative ability to go to war and to ratify treaties. The Commons has only been able to vote on these decisions after the fact and in restrictive ways – e.g. via moving a no confidence motion in the government. The Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 curtailed the treaty ratifying power and put it on a statutory basis. Its new provisions will be very important if the withdrawal agreement from the EU will be in the form of a treaty, as this would require the approval of the UK Parliament (and of the EU Parliament) before it became binding.

The ability to commit UK armed forces to war appears to have been replaced through a new convention that MPs should vote on major actions before they are undertaken. In 2003, MPs approved action in Iraq (but influenced by a ‘dodgy dossier’ prepared by the Blair government). MPs also voted in 2011 for action in Libya against Gadaffi (although operations had in fact already begun). And in August 2013 MPs defeated a proposal by the Coalition to take military action against the Assad government in Syria. A year later a diametrically opposite motion for air strikes against IS (Islamic State) in Iraq (but not in Syria) was approved by the Commons. In December 2015 the Tory government won a vote with a 174 majority to extend anti-IS air strikes to Syria in December 2015. This sequence would seem to suggest that the power to go to war is now subject to approval by the Commons. However, in mid-2016 it emerged that some UK ground forces were being secretly deployed in anti-IS actions in Libya, with no notification to Parliament.

What do fixed term parliaments mean?

The rules passed under the Coalition require a PM with a Commons majority to call the next general election on a five-year fixed timetable. Should the PM resign, as David Cameron did in June 2016, the process to be followed (as indeed it was in 2016) is that the governing party will elect a new leader, and that leader will be asked by the Queen to form a government. However, should the PM lose a no-confidence vote instead, the process to be followed is still unclear. The monarch could ask another member of the largest party to try to form a government. But if they too declined, conceivably the Leader of the Opposition could be asked to, and might seek to, form a minority government within a 14-day period under the Act, without any immediate dissolution. To dissolve Parliament early a vote of two-thirds of MPs is needed, which would normally require that (most) MPs from both the government and the main opposition should support the motion. This last route was the one successfully followed in April 2017, when a supermajority of 522-13 backed the government’s motion for a new election.

EVEL: English Votes for English Laws

A second potentially far-reaching (or potentially temporary) change for Parliament followed from Labour and the Liberal Democrats’ rather credulous decision to support the Conservatives to defeat the Scottish National Party’s independence referendum in summer 2014. The three parties solemnly pledged a major granting of powers to the Edinburgh Parliament, and the morning after the result became clear Cameron announced that the deal would be implemented. However, it would be with a previously hidden codicil that changes would be introduced to allow English and Welsh MPs to vote alone in the Commons on laws just affecting them.

After the Conservatives’ 2015 victory this substantial constitutional change was peremptorily implemented by a single majority vote to change the House of Commons’ Standing Orders. So the growing pseudo-convention that UK constitutional changes require a referendum (buttressed by the 2011 referendum on the Alternative Vote, and the 2014 Scotland vote) was wrecked at a stroke. There was no real public consultation, no House of Lords vote on the change, no Supreme Court decision on the scheme and no judicial review.

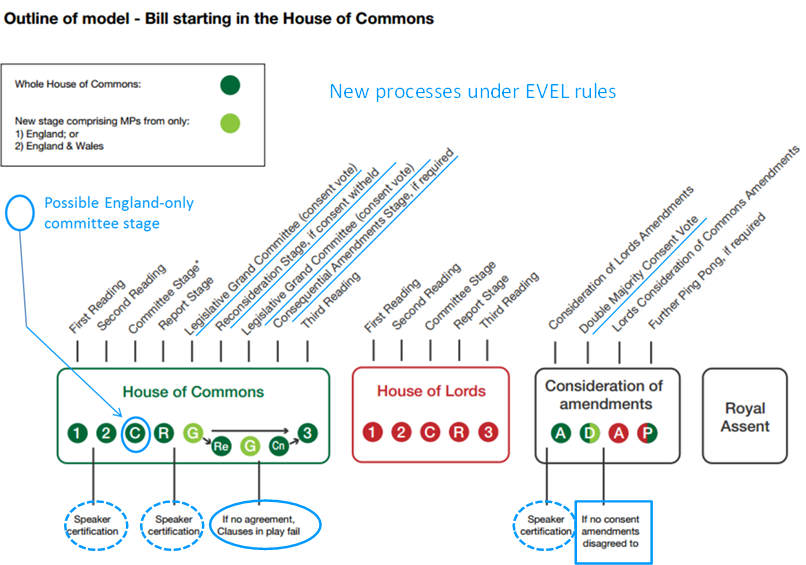

In essence the EVEL provisions made these changes:

- a new ‘England-only’ committee stage for laws affecting only England (and including Welsh MPs for E&W laws);

- a ping pong process between the committee and full House (including other MPs) is possible at Report stage; and

- (iii) at the close of the Commons’ consideration, a Legislative Grand Committee of only England MPs votes to accept or reject the final bill as a whole.

- The House of Lords process is not changed. But a Commons Grand Committee composed of only English MPs considers any Lords amendments, as well as full the Commons.

The government’s explanation of how the English Votes for English Laws process will work is summed up in this diagram. The new processes are highlighted in blue.

The main components are covered above, but note that the Speaker is repeatedly involved in determining which laws or provisions within laws must be subject to this procedure, conceivably subject to overview by Supreme Court. The Public Administration and Constitution Committee’s 2016 report on EVEL is highly critical. Together with politicising the office of the Speaker, Daniel Gover and Michael Kenny have identified and evaluated four additional criticisms surrounding EVEL: that English and Welsh MPs have the power to veto laws passed by the entire House; that the process undermines that way the coherence of UK-wide government; that it is too complex; all while it fails to facilitate a meaningful expression of England’s voice. Their evaluation of the first year of the process found that in practice, the force of the first three objections is limited by key features, like the double veto that is required. But it also found that criticism pertaining to complexity and the meaningful expression of the English voice do remain an issue. Whether the scheme will be much used, and if it can survive a non-Tory majority, both seem dubious at present.

Scrutiny of the executive

The prime minister’s active participation in parliamentary proceedings is a key mechanism for ensuring the accountability of the executive, but they have been less and less present in the Commons since the time of Thatcher and Blair. The Prime Minister’s attendances are now limited to a single 30 minute question time (PMQs) once a week when Parliament is sitting, occasional speeches in major debates, and periodic public meetings with the chairs of Select Committees in the new Liaison Committee. More encouraging is recent research showing that backbenchers used PMQs in 1997-2008 as a key public venue, with backbenchers often leading the agenda and breaking new issues that later grew to prominence. The current Leader of the Opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, has also routinely been using PMQs to ask questions sent in on email by the public, somewhat changing the tone of the session.

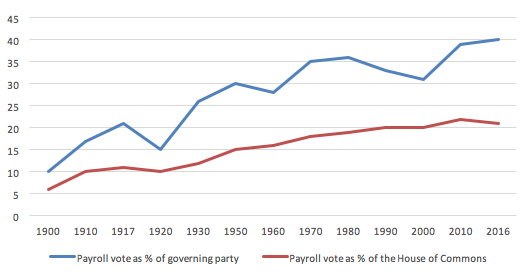

The ‘payroll vote’

Parliament’s independence vis-a-vis the executive has long been qualified by strong partisan loyalties amongst almost all MPs, who (after all) have spent many years working within parties before becoming MPs. The members of the government’s frontbench are expected to always vote with the executive, as are Parliamentary Private Secretaries (who are pseudo-ministers). The last official data in 2010 showed approximately 140 MPs affected. Unofficial estimates of the size of the payroll vote suggest that by 2013 it was equivalent to well over a third of government MPs. Given the smallish number of Conservative MPs in the 2015 and 2017 Parliaments, the ratio will still be high. When Commons seats fall to 600, the prominence of the payroll vote will increase, unless government roles for MPs are cut back.

Figure 2. The payroll vote 1900-2016

Sources: Who Runs Britain? / Commons Library

Dissent by backbench MPs

The coalition period marked not just a period of record dissenting votes by backbenchers against their party line, but also the extension of this behaviour to larger and more consequential issues. The cleavages inside the Conservative party between pro and anti-EU MPs are exceptionally deep. During the summer of 2016 the Cameron government backed off several controversial legislative proposals, and proposed an exceptionally anodyne set of bills in the Queen’s Speech, apparently to avoid straining party loyalties further in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum. The rise of serial backbench dissenter Jeremy Corbyn to becomeLabour leader has also created a serious gulf between his team and many of the Parliamentary Labour Party, which may reduce the cohesion of the main opposition party’s voting.

Conclusion

Public confidence in Parliament was very badly damaged by the expenses scandals of 2009, and trust in the House of Commons remains at a low ebb, despite some worthwhile but modest reforms in the interim, which made Select Committees more effective in scrutinising government. The Commons remains a potent focus for national debate – but that would be true of any legislature in most mature liberal democracies. There is no evidence that the UK legislature is especially effective or well-regarded, as its advocates often claim.

Five years of Coalition government 2010-15 somewhat reduced executive predominance over Parliament – as they were almost bound to do – and the return of a hung Parliament in 2017 may do so again. But even this recurrence may not break traditions of strong executive control over the Commons. Tory divisions over the EU (plus the artificial exclusion of UKIP from Commons representation) perpetuated backbench unrest after 2015, but UKIP’s almost-demise has not lessened tensions between Leave and Remain-inclined Conservative MPs. After 2017, there were some signs of an amelioration of party discipline and more cross-party working being possible, but they may still be temporary. Structural reforms to make the Commons a more effective legislature, and to modernise ritualistic behaviours and processes, are still urgently needed.

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group.

Artemis Photiadou is Managing Editor of the LSE British Politics and Policy blog.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE, co-director of Democratic Audit and Chair of the Public Policy Group.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/jAAwnk39xp

How effective is #Parliament in controlling #UK govt and representing citizens? https://t.co/vEZRxIxHcl @democraticaudit #cdnpoli #democracy

In depth review: How effective is the UK Parliament in representing the people.

https://t.co/FY2PacNnTw

Does parliament effectively represent the people? Indepth analysis from @artemisq & @PJDunleavy via @democraticaudit https://t.co/LKKInIE84J

@overmightyvoter Parliament and Executive. https://t.co/r7fjUzj0V3

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/JHCnvqd1Kb

[…] How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? In the latest installment of our 2016 Audit of Democracy, Artemis Photiadou and Patrick Dunleavy consider how well the House of Commons functions as a legislature. Is Parliament still an effective focus of national debate and close control of the executive? And how well does the Commons function in scrutinising and passing legislation, or monitoring policy implementation? What does democracy require for the legislature in focusing national debate, and scrutinising and controlling major decisions by the executive? Recent developments The first peacetime coalition since 1945 between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats marked out 2010-15 as an unusual period of Parliamentary relations with the government. […]

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/Wcly1xI8wg

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/0UuKHNub5L

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/9yEgP7hPBq

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/r7fjUzj0V3

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/5UbeNs5jsp

Excellent post on ‘How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens?’ https://t.co/x7BhW6GUrd

How effective is Parliament in controlling UK government and representing citizens? https://t.co/TrPXyc5fSf https://t.co/yM8U3S9qcX

@democraticaudit @LSEpoliticsblog Parliament represents the interests of the crony donors and ignores the electorate, totally undemocratic.