Parliamentary websites, transparency and the quality of democracy: where does the UK stand?

Parliamentary websites can help people engage with elected representatives and the democratic process. Devin Joshi and Erica Rosenfield have been comparing the websites of legislatures across the world. Here, they share their findings on how the UK Parliament compares to its international counterparts, finding it an excellent model worthy of being emulated elsewhere, with some room for further improvement.

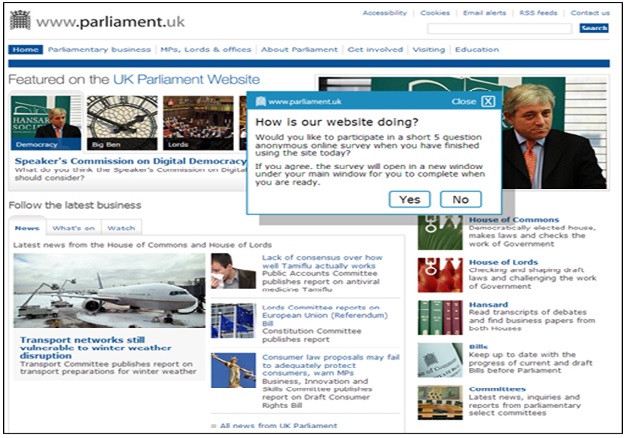

How well does Parliament’s website help encourage people to engage with democracy? Credit: Parliamentary copyright

In the digital age, new modes of online communication have great potential to improve the quality of democracy by bestowing citizens with the ability to easily communicate their ideas and concerns both horizontally with other citizens, and vertically with policy-makers and government leaders. Parliamentary websites, in particular, can be a powerful vehicle to enhance political communication as well as transparency, participation, representation, and accountability, all of which are crucial to the quality of a liberal democracy.

In an attempt to set universal benchmarks for good practice in the design and operation of parliamentary websites, the Inter-Parliamentary Union established in 2000 certain minimum and desirable criteria that websites should meet in order to serve their citizens. Roughly a decade after the IPU established these guidelines we assessed parliamentary websites around the world and found their presence to be nearly universal. As of April 2011, 184 out of 193 countries had a functioning website for their lower or unicameral house of parliament. Focusing on transparency and communication between citizens and Members of Parliament (MPs), our study centred on whether parliamentary websites are providing citizens with basic contact and background information about their MPs and links to social media. At the outset of our study, we hypothesized that they would provide greater MP transparency in countries that were affluent, democratic, and which had compulsory as opposed to voluntary voting.

Broadly speaking, our analysis confirmed these hypotheses, but also revealed some surprising results. On the positive side, many low-income countries and even some non-democracies are providing a substantial amount of MP information online. Conversely, many established democracies provided shockingly low degrees of MP transparency and in all regions of the world, more than half of parliamentary websites failed to provide even the most basic information to enable citizen communication with their MPs, namely MP office addresses and phone numbers. Even in Europe and the Americas, only 75 percent of websites provided the email addresses of MPs. Our full study was published in the Journal of Legislative Studies in December 2013.

How does the UK compare with other countries? On a scale from 0 to 12, the UK parliamentary website scored a 7 in April 2011 when our study was conducted. Germany and Singapore ranked the highest; both scored a 12 on our MP transparency rating, which is based on the provision of MP background and contact information. Today, the UK’s overall rank would be unchanged according to this metric. In terms of background information (sex, age, profession, education, marital status and religion), the UK’s website still only provides the sex of MPs. The score on contact information is also unchanged, although the site provides more information in this domain. Importantly, the UK’s PW continues to provide all MPs’ party affiliations, constituencies, committee memberships, email addresses, phone numbers and office locations.

While the overall transparency rating of the UK Parliament’s website is unchanged, it has improved in one major area. Whereas in 2011 the website did not provide links to MPs’ personal websites, today these links are widely available, along with links to MPs’ Twitter feeds, if applicable. The homepage includes links to various popular social media sites, enabling visitors to quickly and easily keep up to date with Parliament via Twitter and Facebook, view images of parliamentary business and events on Flickr, and view films explaining the work and history of Parliament on YouTube. Also, when one first arrives at the website of the UK Parliament, a pop-up screen asks visitors to the website to provide feedback on how the site is doing (see image above).

The survey asks the participant’s role in visiting the website (e.g. as a student, a journalist, a member of the public, and so on); what s/he was looking for on the site (such as information on bills and legislation, committee information, information about MPs or Lords, how to contact your MP, historical information, and so on); if the viewer found what they were looking for; and other questions on the technical quality of the website. This is an important step that certainly bodes well for the overall transparency of the site. By directly soliciting the public’s input into what they are seeking to find on the website, the overall quality and transparency will presumably be improved over time.

Parliamentary websites should be included in the audit of democracy conducted by Democratic Audit, and their strengths and deficiencies ought to be acknowledged. Highly transparent, informative, and interactive websites can enhance both a country’s degree of democracy as well as its quality of democracy by facilitating and encouraging meaningful two-way communication between citizens and their elected representatives. Regarding the latter, the UK’s parliamentary website is an excellent model, and while there is certainly room for improvement, nations struggling with e-governance and parliamentary transparency would be well-served by emulating many aspects of the UK Parliament’s website.

In an apparent acknowledgement of the progress still to be made by the UK in the realm of e-governance and online transparency, the Parliament of the UK recently announced the setting up of a new Commission on Digital Democracy, which is advertised prominently on the homepage of the parliamentary website. According to the site: ‘this Speaker’s Commission will explore how British democracy can meet the demands of the digital era and modern citizens…and how to reconcile representative democracy with the technological revolution.’ With a report expected to come out in early 2015, it will certainly be interesting to analyze and monitor their recommendations.

—

This post is based on the following research paper: Joshi, Devin and Erica Rosenfield, ‘MP Transparency, Communication Links and Social Media: A Comparative Assessment of 184 Parliamentary Websites’, Journal of Legislative Studies Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013.

Note: This post represents the views of the authors and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1iq0sQp

—

Devin Joshi is an Assistant Professor in the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, Colorado, USA, email: devin.joshi@du.edu

Devin Joshi is an Assistant Professor in the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, Colorado, USA, email: devin.joshi@du.edu

Erica Rosenfield is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, email: erica.rosenfield@alumni.utoronto.ca

Erica Rosenfield is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, email: erica.rosenfield@alumni.utoronto.ca

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

its important to have transparency but more importantly it is to have websites that are understandable for all levels of society both in design and language used.

Parliamentary websites, transparency and the quality of democracy: where does the UK stand? : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/GBUM2y9W02

politics-web

“@se_kip: I have always, personally, felt the UK Parliament website is absolutely rubbish. am I right? https://t.co/Nw2PGaeYEc”

“Parliamentary websites, transparency and the quality of democracy” Via @democraticaudit #ldbytes https://t.co/JySG87NMjw

RT @democraticaudit: RT @eurorights: Democracy: Extremely interesting results revealed by study on parliamentary websites @democraticaudit …

Qualité de la démocratie, transparence et sites web des partis (arrêtez d’écouter les marketeux, soyez citoyen) https://t.co/weB9N72T7j

I have always, personally, felt the UK Parliament website is absolutely rubbish. But am I right? https://t.co/FQhVXAc6Zl

How transparent is the @UKParliament website and how does it compare to other countries? @democraticaudit’s review: https://t.co/HB3laNo6il

Democracy: Extremely interesting results revealed by study on parliamentary websites @democraticaudit https://t.co/tS6vdM4GKD

Great new DA post today: Parliamentary websites, transparency and the quality of democracy-where does the UK stand? https://t.co/jbJgdHBdRW

How good is Parliament’s website? New research on Democratic Audit compares it to equivalents overseas. https://t.co/EXv6rzwJdS

When I visited the National Diet Library Japan last year, they praised the UK and Scottish Parliament websites.

Interesting @democraticaudit post – how does the UK Parliament website compare internationally? https://t.co/QGaLhMluWM #opendemocracy

Parliamentary websites, transparency and the quality of democracy: where does the UK stand? https://t.co/JYnL5WA0on

How does the UK Parliament website compare to international counterparts? New on Democratic Audit: https://t.co/f6ejNq4m0O