Compulsory voting may reinforce the resentment young people feel toward the political class

With young people much less likely to vote than older generations, it has been proposed the UK follow other countries such as Belgium and Australia by introducing compulsory voting, with IPPR suggesting only first-time voters should be forced to participate. Matt Henn and Nick Foard consider the merits of this proposal using data from a recent survey of voting intentions, concluding it would risk increasing the disconnect between young people and democracy. This post is part of our series on youth participation.

With young people unenthusiastic or resentful about politics, is compulsory voting the answer? Credit: Sueno, CC BY 2.0

What might be done to re-connect today’s youth generation to the formal political process and to convert their broad democratic outlooks into attendance at the ballot booth? Is compulsory voting the way forward? Recently, a report from Sarah Birch and IPPR has suggested that one way to arrest the decline in youth voter turnout is to introduce a system of compulsory voting for first-time voters. This suggestion is not as radical as it might at first seem. There are several established democracies that have compulsory voting laws, including Belgium, Australia, Greece, Luxembourg – and several more which have all had such systems for at least a period during the modern era (such as Italy, Austria, and the Netherlands).

There would certainly appear to be some major advantages should voting be made compulsory for first time voters. At present, there is a momentum developing in Britain for the idea of extending the vote to 16 and 17 year olds; the Labour party are considering making this part of their platform for office at the next general election, while these younger groups will be granted the right to vote at the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014. It is also argued that compelling these young people to vote will help towards eliminating the generational electoral divide. In doing so, it will force professional politicians, the political parties and future governments to treat young people and their policy concerns more respectfully and on a par with those of their older contemporaries. Furthermore, evidence suggests that voting (and by implication, non-voting) is habit-forming (Franklin, 2004). Consequently, requiring young people to vote will help shape their commitment to voting in the future.

A major drawback of introducing such a compulsory voting scheme for young people is that it singles them out as ‘different’ from the rest of the adult population, helping to reinforce the stereotype of this current youth generation as apathetic and politically irresponsible. The implication being that it is the behaviour of young people that needs changing – rather than a reform of the political process and of democratic institutions to make the latter more accessible and meaningful for today’s youth generation. Furthermore, critics might argue that compelling any young person to vote who has only limited interest in mainstream electoral politics or who feels no affinity with the parties on offer, has serious negative implications for the health of our democratic system; by forcing them to vote, they may develop an attitude of entrenched disdain for the parties, or indeed become particularly susceptible to parties with antidemocratic tendencies – especially those of the far-right. However, offering the option to vote for ‘None of the above’ on the ballot paper may help militate against this latter point.

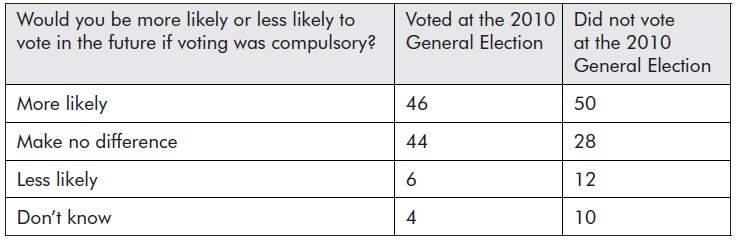

In our research study, we asked young people if the introduction of compulsory voting would make a difference to their turnout in future elections. Perhaps not surprisingly, the largest group (47 per cent) said it would, although a large minority (40 per cent) reported it would make no difference. Of particular note, Table 1 compares the views of those young people claiming to have voted at the 2010 General Election with those reporting that they had not. These ‘Voters’ and ‘non-voters’ were similar in stating that that they would be more likely to vote in the future if compulsory voting were introduced (46 per cent and 50 per cent respectively). However, 28 per cent of those who didn’t vote in 2010 said that compulsory voting would make no difference – and that they would continue not to vote. Furthermore, and perhaps worryingly, twice as many previous non-voters (12 per cent) than voters (6 per cent) stated that they’d actually be less inclined to vote in the future should compulsory voting be introduced.

Table 1: Compulsory voting by voting behaviour at the 2010 General Election (%)

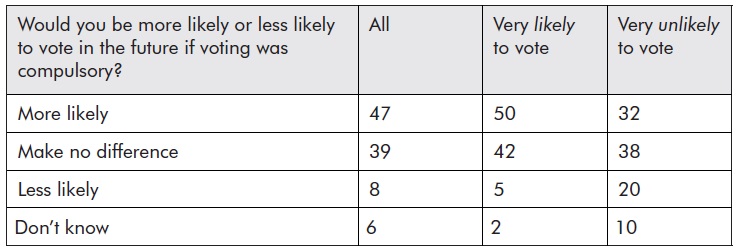

Projecting forward, our results reveal important attitudinal differences between those already planning to vote at the next general election, and those intending to abstain. As Table 2 reveals, 58 per cent of those reporting that they were already very unlikely to vote felt that compulsory voting would make either no difference to this decision (38 per cent), or indeed make them even less likely to vote (20 per cent). From this we can infer that the introduction of compulsory voting would merely serve to reinforce existing feelings of resentment.

Table 2: Compulsory voting by likelihood to vote at the next General Election (%)

Does compulsory voting represent a viable solution to the on-going disconnect between young people and the democratic process? It would seem that more young people would vote if such a system were introduced – not surprising if such a system were mandatory. However, whether or not this would mean that they would feel truly connected to the democratic process remains in question. Indeed, forcing young people to vote when they feel such a deep aversion to the political class may actually serve to reinforce a deepening resentment, rather than to engage them in a positive manner and bolster the democratic process.

—

This post is part of a series on youth participation based on the Political Studies Association project, Beyond the Youth Citizenship Commission. For further details, please contact Dr Andy Mycock. An electronic copy of the final report can be downloaded here.

Note: This post represents the views of the author and dies not give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1hWFM3Z

—

Matt Henn is a Professor of Politics and International Relations at Nottingham Trent University.

Matt Henn is a Professor of Politics and International Relations at Nottingham Trent University.

Nick Foard is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Nottingham Trent University.

Nick Foard is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Nottingham Trent University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

An important additional consideration is that if something is compulsory it implies a penalty against those who will not obey the order, or who will not accept being frogmarched down to the polling station. Presumably the bottom line is a criminal record – even if just 60,000 refuse to pay the fine or will not turn up for the sanctions imposed by the court, they are liable for a criminal record and potentially jail. Is this what we want? And do we have the prison places for them? And is this entirely wise?

“A major drawback of introducing such a compulsory voting scheme for young people is that it singles them out as ‘different’ from the rest of the adult population, helping to reinforce the stereotype of this current youth generation as apathetic and politically irresponsible. The implication being that it is the behaviour of young people that needs changing – rather than a reform of the political process and of democratic institutions to make the latter more accessible and meaningful for today’s youth generation. … by forcing them to vote, they may develop an attitude of entrenched disdain for the parties, or indeed become particularly susceptible to parties with antidemocratic tendencies – especially those of the far-right.”

You forget the inventiveness of the resentful – youthful or not. I don’t think it will be the far-right that stand to gain, but colourful fringes. Students will club together to raise the deposit and nominate “legalise pot”, “sack the bursar”, “condoms for all”, “pirate” even “party party” candidates. Even the old Monster Raving Loonies may benefit. Some of these candidates could get elected – at least to council seats.

Alternatively what do you do when you get mass-boycotts of compulsory elections? Civil disobedience is a well-established response to coercion. Outside marginal seats – where you vote does not matter anyway, this could be very attractive. Take political action – stay in bed!

Compulsion can’t be the way forward – https://wp.me/pUTZ7-3C

And what exactly does “compulsory voting” entail? The polling clerk standing over the voter to make sure that they make a mark on their ballot paper and then put it in the box? I hope not – the ballot is meant to be secret. I guess they could scan all ballot papers to read the serial numbers and then cross-reference them back via the counterfoils to the marked register – that would be even creepier.

So what does forced voting in practice have to mean … turning up at the polling station and being marked off? What about postal votes … some form of compulsory returning of postal votes (guess that means having to use some form of recorded delivery mailing to ensure that you can prove you did so)?

So once you have done your “civic duty” and been marked off, how do the authorities wish to ensure that refuseniks do not decide to have say a ballot-paper air-plane dog-fight in the polling station? Or just pocket the ballot paper and walk out – which I suspect is illegal, but how does a busy polling clerk enforce that rule?

Would compulsory voting be counter-productive in increasing the political engagement of young people? https://t.co/31DzpjPnCs

IPPR proposal for Compulsory voting may reinforce resentment young people feel toward political class – Henn & Foard https://t.co/84cKcsEMIB

Compulsory voting may reinforce the resentment young people feel toward the political class https://t.co/3KB5y3Nv0Y

Compulsory voting may increase youth resentment towards politics argues Matt Henn https://t.co/JceM3pnK7g @ElectoralCommUK @electoralreform

Compulsory voting may increase youth resentment towards politics argues Matt Henn https://t.co/JceM3pnK7g @TrentUni @IPPR @HansardSociety

‘Compulsory voting’ [Me; bone-headed, self-serving, arrogant obtuse thinking by the political class] #elections2014 https://t.co/W21NwvoKE3

Compulsory voting is one of the most bone-headed, self-serving, arrogant pieces of obtuse thinking to come of of the political classes in the UK. There is something fundamentally wrong with politics and the political class when we get to the situation of 60% of an electorate not voting for anyone – and that excludes the steadily growing large number of non-registered potential voters. It will certainly not be attributable in any significant way to voter so-called ‘apathy’ (that is in fact more often than not likely to be an active deliberate decision not to participate – not to legitimise the unpalatable or the unacceptable. I have not yet one comment from a senior UK politician – UKIP included – expressing any concern, still less shame or embarrassment, at their getting into power through such a dissolute and unrepresentative system of politics. Look to yourselves in the political class across the UK, before you stoop to compelling and sanctioning voters and

IPPR’s Compulsory voting idea could just reinforce the resentment that young people feel toward the political class https://t.co/cl8yvgf0ls

Thank goodness someone has posted this. The proposal to single out a disenfranchised group for special sanctions and demands in order to make them *less* hostile to the political system is perverse.

Compulsory voting may reinforce the resentment young people feel toward the political class https://t.co/dqBxswe0Qz