Evidence from Portugal shows that citizens in corrupt areas are more likely to vote in elections

Corruption is a persistent problem in several countries across Europe. Daniel Stockemer and Patricia Calca write that corruption can have two distinct effects: it can either result in citizen disengagement from the political process, or it can lead to increased voter participation as a mechanism for punishing political authorities at the ballot box. Using an analysis of local level data in Portuguese elections, they illustrate that the most corrupt areas in the country also had higher voter turnout rates, suggesting that in Portugal, corruption acts as an incentive to participate in elections.

There is widespread evidence that political corruption, or the misuse of public office for private gain, has negative influences on the economic and social well-being of countries. However, while plenty of support can be found that bribery, money laundering and the exchange of money for personal gain brings down investment and renders bureaucracies ineffective, it is less clear how citizens react to corruption when they vote. Do enraged citizens rush to the polls to punish corrupt politicians or do they become disgruntled and politically disengaged?

Portugal is the fourth most corrupt country in Western Europe and also has among the lowest turnout rates of western European states. While these national trends make it unlikely that high national levels of corruption are a mobilising agent for higher turnout, it is unclear if the same relationship exists at the local level, where arguably citizens are most strongly affected by bureaucratic performance and efficacy. Certainly, it might be that the more corrupt areas are, the more citizens become disgruntled and the more likely they are to stay at home on Election Day.The existing dozen or so studies largely support the latter of the two propositions. They report that corruption is negatively related to electoral turnout. However, research on the topic is still in its infancy. In particular, almost all existing studies have a national focus. They use national boundaries as their level of analysis, thus overlooking significant intra-country variation in both the independent variables and the dependent variable of interest. Using Portugal, a southern European country with a relatively large corruption problem as a case study, we investigate the corruption turnout nexus with local level data.

However, it might also be the case that citizens mobilise more in areas with higher levels of corruption. For example, individuals in the most corrupt parts of the country might suffer disproportionately because private investment might go elsewhere and infrastructure projects might get delayed. Having a better off region as an empirical referent might entice citizens in a more corrupt region to turn out in larger numbers, to ensure that their local representatives are, at least, not more corrupt than the national average.

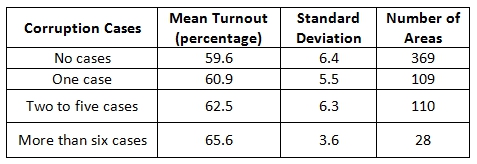

Based on data from the 2005 and 2009 Portuguese elections, we test which of the two stipulations, if any, are true. The number of corruption cases brought to court ranges from 0 to over 50 for Portugal’s municipalities in the two years prior to Portugal’s legislative elections in 2005 and 2009. Due to the fact that the data is skewed towards areas with zero or a few corruption cases, we created a categorical corruption variable and coded the 369 data points with no corruption charges as 0, the 109 observations with one corruption case in the two years prior to the election as 1, the 110 cases with 2 to 5 corruption cases as 2, and the 28 with more than 6 corruption cases in the two years prior to either the 2005 or 2009 legislative election as 3. Turnout, the dependent variable, also varies significantly. It ranges from 40 per cent for the municipality of Vila do Porto, to 74 per cent for the municipality of Sardoal.

Table 1 displays the descriptive relationship between the categorical corruption variable and turnout, highlighting a positive relationship between more corruption and higher turnout. These descriptive statistics indicate that turnout increases by nearly 6 percentage points from less than 60 per cent for municipalities with no corruption cases, to 65.5 per cent for municipalities with 6 or more cases. This relationship is robust and confirmed in an LSD comparison test and a multivariate regression model, in which we control for municipalities’ material affluence, unemployment, the percentage of senior citizens, the closeness of the election and the district magnitude.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics measuring the relationship between corruption and turnout

Note: The Table illustrates that those areas with higher numbers of corruption cases also experienced higher rates of voter turnout. For full calculations see the authors’ longer paper.

While our study clearly indicates that within Portugal highly corrupt areas have higher turnout than less corrupt areas, our research has two caveats. First, we have no information on who the individual voters are and which political figures have been indicted on corruption charges. Hence we cannot determine whether this increased mobilisation strengthens the country’s democratic credentials. This would be the case if (more) individuals rush to the polls to punish corrupt individuals and to clean up the country’s political system. In contrast, if higher mobilisation comes from voters who have been bought off or promised government spending, then the country’s democratic credentials could be severely harmed.

The second caveat in our study is that we cannot determine with certainty that the official corruption numbers capture the actual presence of political corruption. There is the possibility that municipalities where more corruption cases are reported are actually less corrupt, because citizens there bring corrupt officials to court. Vice versa, regions with less corruption cases could actually be more corrupt, if everyone there accepts that politicians are paid for favours and give out perks based on their clientelistic networks. However this scenario would imply that most or all relevant actors participate in these corrupt practices, a scenario that is rather unlikely in today’s globalised and Europeanised world.

—

Note: This post originally appeared on Europp – European Politics and Policy. For a longer discussion of this topic, see the authors’ recent paper in Crime, Law and Social Change. This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position Democratic Audit, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Daniel Stockemer is Assistant Professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. His work has included research on political participation, elections, social movements and democracy and democratisation.

Daniel Stockemer is Assistant Professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. His work has included research on political participation, elections, social movements and democracy and democratisation.

–

Patricia Calca is a PhD Candidate at the University of Lisbon and a Teaching and Research Assistant at the University of Mannheim. Her work includes research on legislative behaviour, comparative politics, formal modeling and political communication.

Patricia Calca is a PhD Candidate at the University of Lisbon and a Teaching and Research Assistant at the University of Mannheim. Her work includes research on legislative behaviour, comparative politics, formal modeling and political communication.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Evidence from Portugal shows that citizens in corrupt areas are more likely to vote in elections https://t.co/PpVIyLAvVe. vía @PJDunleavy

Complex effect of corruption allegations on voter turnout in regions suffering compared to nation. Not good 4 Nat? https://t.co/38F4VdTtw4 …

RT @fundacioncd: Are people from corrupt areas more likely to vote? The evidence from Portugal says yes https://t.co/MAuFh2C87B @democratica…

“@democraticaudit: Are people from corrupt areas more likely to vote? The evidence from Portugal says yes https://t.co/cCLh3zEl8e” #Nigeria

Are people from corrupt areas more likely to vote? The evidence from Portugal says yes https://t.co/CLCZthbwcR

Evidence from Portugal shows that citizens in corrupt areas are more likely to vote in elections https://t.co/byE5PuisH7

Evidence from Portugal shows that citizens in corrupt areas are more likely to vote in elections https://t.co/1CQUZQCYnF